From textbook to trust

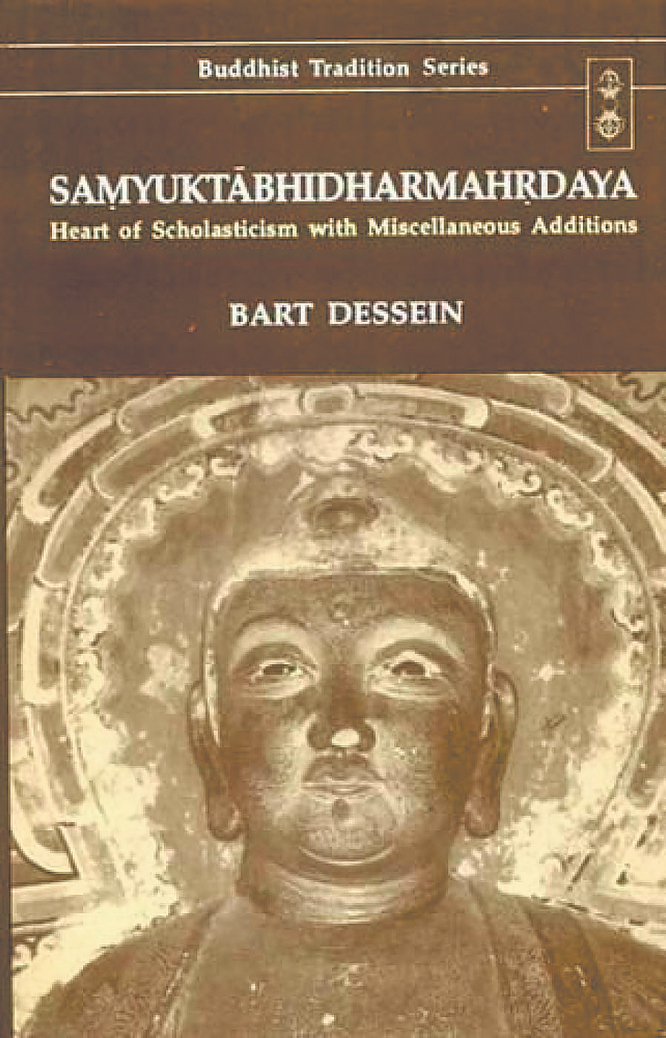

Bart Dessein, a Belgian sinologist, immersed in China's language and culture for 40 years, is building bridges between the country and Europe

Rediscovering culture

Dessein's research trajectory — from Buddhist philosophy to Confucianism and New Confucianism — reflects not only his scholarly curiosity but also his attentiveness to China's evolving society.

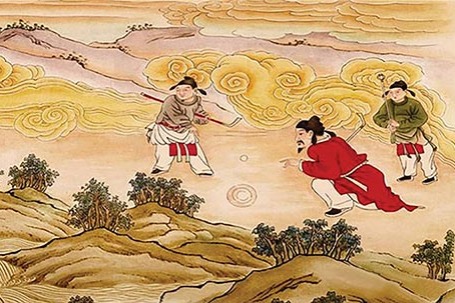

"If you study Chinese Buddhism, you inevitably encounter Confucianism," he explains. "From the Wei Dynasty (220-265) onwards, Buddhism influenced Confucianism. They are inseparable." His later turn to New Confucianism stemmed from a desire to understand contemporary China. "What struck me was that after a period of harsh criticism, Confucianism regained importance in modern society. I wanted to explore why, and what this says about China today."

He attributes this revival to China's growing international confidence. Once derided as a cause of weakness, Confucianism is now recognized as part of China's cultural strength. "No culture has a future without its history. Confucianism is part of China's roots. As China's global status rises, it realizes that not everything in the West is superior. This is not arrogance, but a rediscovery of cultural advantages."

Confucian ideas, he argues, still have practical value. The philosophy of xiushen (self-cultivation), which emphasizes personal moral responsibility, remains relevant. "If every individual strives to become a 'junzi' (gentleman), the whole nation improves. Confucianism is not against development. On the contrary, its focus on moral self-improvement can contribute to modernization."

On the concept of modernization itself, Dessein stresses that it need not equate to Westernization. "China has its own historical background. Chinese modernization inevitably includes elements of traditional culture. Western culture has strengths, but it is not the standard. Every country should absorb foreign culture according to its own needs, just as Buddhism integrated into Chinese culture and became part of it."

He believes Chinese philosophical traditions also offer insights for global challenges. The concept of tian ren he yi (harmony between heaven and humanity), for example, provides a counterpoint to the Western idea of conquering nature. "This perspective encourages us to rethink the relationship between human development and the natural environment. It can help address issues such as climate change."

That's why he insists that equality must be the foundation for cultural exchanges. "If you start from a Western-centric point of view, you will never understand other cultures. Differences should not be dismissed as negative. We must ask why they exist. Even if we do not agree, trying to understand is essential."

From tracing Buddhist manuscripts to analyzing modern reinterpretations of Confucianism, from building academic networks to advising young Europeans, Dessein has spent four decades weaving intellectual and personal ties between China and Europe.

As China continues to develop and Europe redefines its role in a globalized world, his message remains simple but profound: empathy, equality, and mutual learning are the cornerstones of meaningful exchange. And in that lifelong exchange, Dessein himself has become not only a scholar of China but also, in many ways, part of its extended academic family.

zhangzhouxiang@chinadaily.com.cn