Japan's white paper for kids raises a red flag

The recent release of the annual defense white paper, "Defense of Japan 2025", by the Japanese government may be a known trick being used by Japan to militarize the country. But what is unprecedented and especially worrisome is the release of a booklet based on the 2024 defense white paper for primary school students. Almost 6,100 copies of a comic book version of the white paper have been sent to about 2,400 primary schools across Japan.

The publication, aimed at upper primary and secondary school students, presents military policies and geopolitical dynamics in an oversimplified, emotionally charged manner, labeling national defense a matter of existential urgency and military strength the ultimate safeguard for Japan. This is especially shocking given that pacifism is enshrined in the country's Constitution.

Comprising colorful illustrations and mascots, the booklet appears harmless. But its message is far from benign. By citing neighboring countries — China, the Democratic People's Republic of Korea and Russia — as looming threats and portraying Japan as the lone sentinel in a hostile region, it sends a dangerous message to young readers: fear your neighbors, trust the military.

It is one thing to teach children the importance of national defense, quite another to ingrain in them a worldview shaped by anxiety and antagonism. Japan's new approach, cloaked in pedagogy but steeped in politics, represents a troubling shift from education to indoctrination.

Equally worrying is the way the booklet frames the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Rather than exploring the complex political and historical roots of the conflict, it sends a singular message: Ukraine lacks a strong military, and is paying the price for it. The underlying message is even more alarming: peace comes not through diplomacy or cooperation, but through superior firepower.

The militaristic worldview fosters binary thinking — us versus them, strong versus weak. It teaches a generation of students to see international relations, not as a way to build mutual understanding, but as a contest of force. In doing so, it feeds a nationalist narrative that legitimizes Japan's departure from its long-held principle of "exclusively defensive defense".

The booklet promotes Japan's "counterstrike capabilities", a significant break from the country's postwar pacifist norms. Although Japan's Constitution renounces war, the publication normalizes aggressive policies by presenting them as a necessary response to a deteriorating security environment. Its goal is clear: to familiarize children with Japan's "need to build a strong military" and shape public opinion in favor of it.

The narrative architecture of the booklet rests on a steady escalation of perceived threats. It claims Japan is part of a dangerous neighborhood, surrounded by nuclear-armed countries that do not share its values, making it easy to portray diplomacy as naive, and deterrence as the only rational option.

Absent from the text is any discussion on peaceful coexistence of countries, regional cooperation, or historical context. There is no mention of Japan's own militarist past or its responsibility in shaping East Asia's security landscape, meaning it completely ignores history.

This kind of message, aimed at children whose critical thinking is still developing, has long-term consequences. It risks instilling in young minds a sense of victimhood and suspicion, while discouraging them from seeing and forming their own views about the outside world. If left unchallenged, it could build a generation that welcomes militarism and views foreign countries with mistrust.

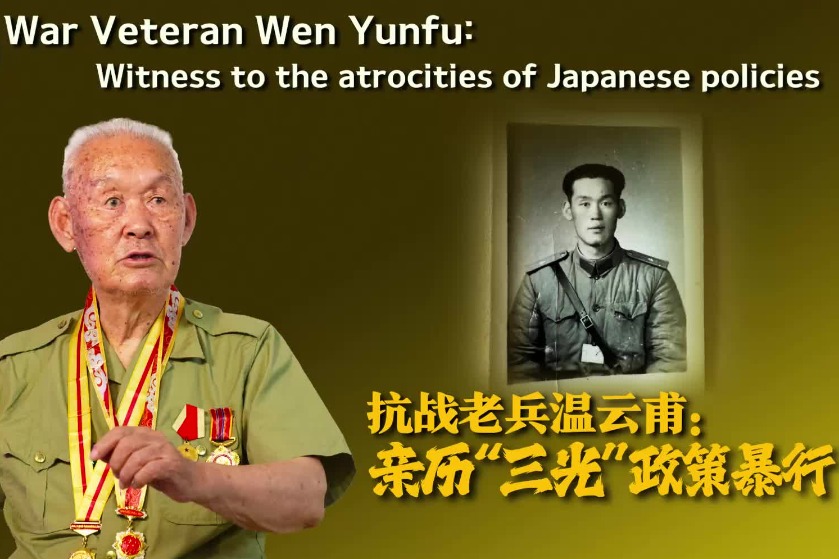

The political timing is hard to ignore. This year marks the 80th anniversary of the victory in the Chinese People's War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression (1931-45) and the World Anti-Fascist War, which should be an occasion for sober reflection. Instead, the Japanese government appears to be reviving the very ideology that led the country down the disastrous path in the 1930s.

Japan has been revising its historical narrative in recent years, softening accounts of its wartime aggression and atrocities in textbooks, and offering vague official accounts on its wartime past. Now, with militarized materials entering elementary schools, Japan is reviving a nationalist form of education reminiscent of its prewar era.

Schools should be sanctuaries for open thought, empathy and critical reasoning, not battlegrounds for ideological campaigns. When governments use education to amplify threat narratives, they undermine the very values they claim to protect. National security may be a legitimate concern, but instilling fear in young minds is a sign of a country's belligerence.

Moreover, the booklet is a thinly veiled military recruitment strategy. With Japan's Self-Defense Forces struggling to meet enlistment targets, the booklet appears designed to inspire children to join the SDF when they grow up. Soldiers are portrayed as noble, military life as honorable and exciting to normalize the presence of military in everyday life.

Fortunately, civil society in Japan is not silent. Several citizens' groups have petitioned the government and are calling for the booklet's withdrawal. Their resistance reminds us that democratic values still have a place in Japan's public discourse.

Japan's move risks fueling regional distrust, exacerbating xenophobia in the country and destabilizing East Asia's already fragile peace. The seeds sown in classrooms today could grow into conflicts tomorrow.

History shows what happens when education is used as a vehicle for militarization. Japan's prewar history offers a cautionary tale that should not be forgotten. At a time when the world is facing growing uncertainty, countries should not propagate fear-based ideas; instead they should foster understanding, dialogue and critical thinking.

Japan cannot afford to repeat the mistakes of the past.

The author is a research fellow at the Institute of Japanese Studies, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

The views don't necessarily represent those of China Daily.

If you have a specific expertise, or would like to share your thought about our stories, then send us your writings at opinion@chinadaily.com.cn, and comment@chinadaily.com.cn.