Bone technician coaxes secrets from relics

Preparing artifacts for examination requires diligence and precision, Wang Qian and Shi Baoyin report in Zhengzhou.

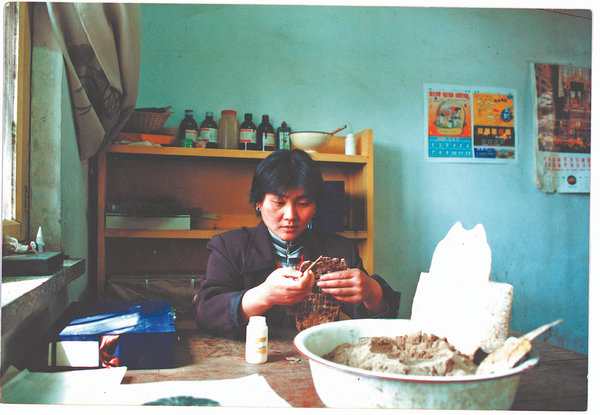

In the quiet laboratories above the country's ancient soil, He Qiaojuan is fully concentrated on the fragile bone under her hands. With a tabao — a delicate ink pad she crafts herself from floss cotton — she coaxes secrets from relics older than empires.

For 35 years, the senior technician from the Institute of Archaeology at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences has been the bridge between China's earliest written words and modern eyes.

"Many misunderstand. They think we ink the artifact itself. Not so," He says.

Her craft is to place the thin xuanzhi, or rice paper, over fragile oracle bones, and apply ink onto the paper with calibrated precision. Too light, the 3,000-year-old inscriptions blur; too heavy, ink bleeds, obscuring history, according to He.

For He, the primary purpose of creating ink rubbings of oracle bones is to protect them, as the technique requires a high level of hand-eye coordination.

Unlike artifacts made of hard materials such as bronze, oracle bones that have been passed down from over 3,000 years ago have undergone burial and erosion, leaving many of them severely weathered and extremely fragile. Therefore, for the artisans who do these ink rubbings, maintaining a stable mindset and absolute tactile sensitivity are both essential.

"It's an art of fencun, exact measure," she says. "Like stamping a seal, but infinitely more delicate."

Her connection runs deeper than career. Born in Xiaotun village atop the Yinxu Ruins in Anyang, Henan province, her mother worked on the archaeological site. Joining the Anyang archaeological team in 1990, she began restoring oracle bones by 1991. As a capital of the late period of the Shang Dynasty (c. 16th century-11th century BC), Yinxu was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2006.

Jiaguwen, or oracle-bone inscriptions, that were excavated from the Yinxu Ruins, were records of practicing divination and praying to gods by the late Shang people. The materials used for divination were mainly cattle scapulas and tortoise shells, as well as other animal bones.

"These bones are incredibly fragile," she says. "If we don't properly record their inscriptions through ink rubbing, research falters."

From the famed oracle bones to the only known bone with turquoise-inlaid characters displayed at the Yinxu Museum in Anyang, she has restored and transcribed thousands of such inscriptions, ensuring scholars access pristine impressions.

Based on the omens deciphered from the cracks made by burning bones, researchers can reconstruct the Shang's royal genealogy. Oraclebone inscriptions are also important materials to study the original configuration of Chinese characters and the earliest state of Chinese language grammar. Due to the efforts of technicians like He, it is made possible for researchers to unlock the ancient secrets.

The 51-year-old technician's expertise expanded in 2000 with the excavation of a bronze wine vessel in the shape of an ox. She started to learn quanxingta (rubbing technique), which turns three-dimensional inscriptions into two-dimensional illustrations on paper. Then she sought mentorship from Guo Yuhai at the Palace Museum in Beijing.

"It requires spatial imagination and ink control," she says. Through layered ink gradients, she makes bronze curves and intricate patterns "stand" on paper — a stark contrast to traditional linear rubbings.

In the process of creating such a rubbing, He must be fully concentrated on completing the task at hand. It usually takes her several days or even a week to finish.

He Yuling, director of the Anyang workstation from the Institute of Archaeology at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, knows He Qiaojuan as one of the few artisans who have mastered the skill across the country.

"It requires deep artifact knowledge, strong aesthetic sense for light and shadow, and technical skills, from making rubbings of individual sections to piecing them together as a whole," He Yuling says, adding that the importance of such technique stems from the human's observation and understanding of the details of artifacts, which is irreplaceable by the mechanical recording of photography or 3D technology.

While mastering the traditional rubbing technique, He Qiaojuan has tried to improve the skill with her own experiments of materials.

To make a rubbing, a dry sheet of rice paper is placed on the surface of a bone or shell and brushed with a liquid containing juice of the roots and stems of Bletilla striata, also known as Chinese ground orchids.

Paper is tamped into every engraved depression of carved characters with a brush. Such preparation creates a uniform, smooth surface. However, the characters carved into bones or stone are filled with a soft material — paper.

"The orchid liquid is sticky, which makes it difficult to lift the paper off. It makes me wonder if there is a better material to get the paper easily applied and removed," He Qiaojuan recalls.

Spending days in library researching for possible solution, He Qiaojuan thought about it day and night. Once, while using distilled water to clean a jade artifact, she had a sudden inspiration to place a sheet of rice paper over the surface of the jade. She found that distilled water not only allowed the paper to adhere closely to the jade but also made it easy to remove. She then tried using distilled water for ink rubbings of oracle bones and found that the results were much better.

Her tools are bespoke with self-made ink pads in varied sizes to navigate microscopic crevices.

The rubbing involves using the soft pad with the right amount of ink inside to carefully tap over the entire sheet of paper. When the soft pad touches the hard surface under the paper, it gives out some ink that is quickly absorbed by the paper. Soft areas, where the carved characters are, do not absorb any ink, or only an insignificant smudge. The rubbing reproduction is distinct — a paper is inked around the characters which stand out as white — unstained.

As museums surge in popularity and the museum craze sweeps the country, intangible cultural heritage experiences, like rubbing, have helped traditional culture reach a wider audience. However, there is also a tendency for people to only scratch the surface, according to He Yuling.

"To achieve deeper cultural transmission, I hope to see more young people in the future engage in immersive exploration, gaining a profound understanding of the beauty of Chinese culture and artifacts," He Yuling says.

He Qiaojuan says that, for the young people who want to learn rubbing, transcending technical skill demands profound reverence. "First, observe the bone," she says. "Learn where it's strong, where it crumbles."

In her silent dialogue with dust and bone, history finds its most faithful scribe.

Qi Xin contributed to this story.

Contact the writers at wangqian@chinadaily.com.cn