Chinese trade was key aspect of maritime struggles

The commercial exchanges, eagerly pursued by European powers, fueled enthusiasm and imagination — if not always genuine understanding — of China.

The exhibition showcases a collection of Chinese blue-and-white ceramics discovered in 2003 from a shipwreck off the east coast of Malaysia. Known as the "Wanli Shipwreck", the Portuguese vessel, dating to around 1625, carried a large cargo of Ming Dynasty porcelain produced during the emperor's reign.

These were displayed alongside their imitations — the result of persistent efforts by European ceramic makers, including Delftware and, later, Meissen porcelain. Delftware, developed in the Dutch city of Delft in the 17th century, was a style of tin-glazed earthenware rather than true porcelain. In contrast, the Meissen manufactory, established in 1710 in the town of Meissen in Saxony, eastern Germany, was the first in Europe to produce true hard-paste porcelain.

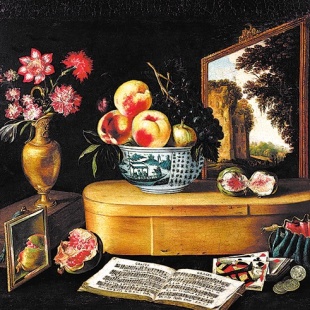

Associated with worldliness, status, and refined taste, Chinese porcelain frequently appeared in Western oil paintings of the time, from still life to religious and mythological scenes.

In a painting by an Italian artist around 1500 depicting Jesus washing the feet of his disciples, the basin used for the ritual is rendered as Chinese blue-and-white porcelain, subtly blending sacred narrative with contemporary symbols of global trade and prestige.

In Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window by the celebrated Dutch artist Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675), a fruit-filled piece of Chinese blue-and-white porcelain sits on the table before the young woman. This subtle detail situates the masterpiece within the cultural context of the Dutch Golden Age, a period when the Netherlands emerged as a global leader in trade, art, science and finance.

Both paintings can be found in the exhibition catalog.

Clashes between established powers and new rivals were inevitable. According to the curator, one of the first major shipments of Chinese porcelain to reach the Netherlands arrived as war booty following a Dutch naval victory over the Portuguese in 1602, off the coast of what is now Malaysia.

As England rose to maritime power following Spain, Portugal and the Netherlands, Queen Elizabeth, who ruled between 1558 and 1603, wisely sought to avoid major conflict while undermining her rivals. This strategy is reflected in her letter to the Wanli Emperor, accompanied by contemporary translations in Latin, Spanish and Italian.

"The apparent assumption is that if no one at the emperor's court could read English, then perhaps they could read one of these alternative languages," says Gao.

She need not have worried. In 1583, Matteo Ricci, the Italian Jesuit missionary, arrived in China and was later granted permission to enter the imperial capital, Beijing, in 1601 — just a year before Queen Elizabeth wrote her letter. One of the earliest Jesuits in China, Ricci, who died in Beijing in 1610, devoted himself to a dual mission: spreading the Christian faith and presenting to his fellow Europeans a more accurate and nuanced understanding of China.

Together with his Chinese collaborators, Ricci translated Confucian classics into Latin, presenting Confucianism as a noble philosophical system rather than a religion. This approach left a lasting impact on Western intellectual thought, extending well into the Enlightenment.

Well versed in Chinese culture, Ricci delivered his observations with great subtlety. As noted in an article by Francesco D'Arelli of the Italian Cultural Institute in Shanghai — featured in the exhibition catalog — Ricci, reflecting on the relative scarcity of world-class "mathematicians and natural philosophers" in China, remarked that this was "because they all devoted themselves to the morality and elegance of speaking, or, to put it better, of writing".