"Both cultures placed deep emphasis on unity, spirituality, and the afterlife," Xue notes. "Egyptians imagined a glorious hereafter, tombs being palaces for the soul, with mummies, amulets, and the Book of the Dead ensuring safe passage through the underworld."

The ancient Chinese shared this longing for permanence. Jade artifacts from the Liangzhu culture (3300-2300 BC), found in tombs along the Yangtze River Delta, were believed to preserve the body for immortality. Later, jade dragons and horses took on a sacred role: to carry the soul to heaven while protecting the body until their reunion.

Some Chinese scholars believe the dragon — Chinese civilization's ultimate totem — may trace its origins to snakes, crocodiles, or both, with crocodiles once common in the Yellow River Basin.

In Egypt, animals were often seen as divine. Hippos symbolized fierce protection; female baboons, maternity; and the scarab beetle — rolling dung across the earth — came to represent rebirth, echoing the sun's daily resurrection.

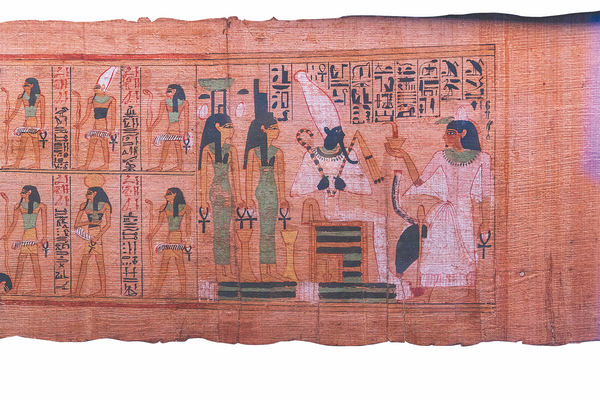

The elegance and realism of ancient Egyptian art reached its height in the depiction of animals, where art most vividly embraced life. A whip handle carved from ivory takes the form of a galloping horse; a cosmetic box mimics the shape of a wild duck; a stone gargoyle, sculpted as a lion, served as both architectural ornament and protector. Animal and human figures were depicted with each feature shown from its most recognizable angle — heads, legs, and feet in profile; eyes and shoulders frontally — creating a composite image that conveyed an idealized, eternal form. This refined visual language, expressed through dynamic, economical lines, lends ancient Egyptian art a timeless, almost modern, sensibility.