Civilizations of the mind

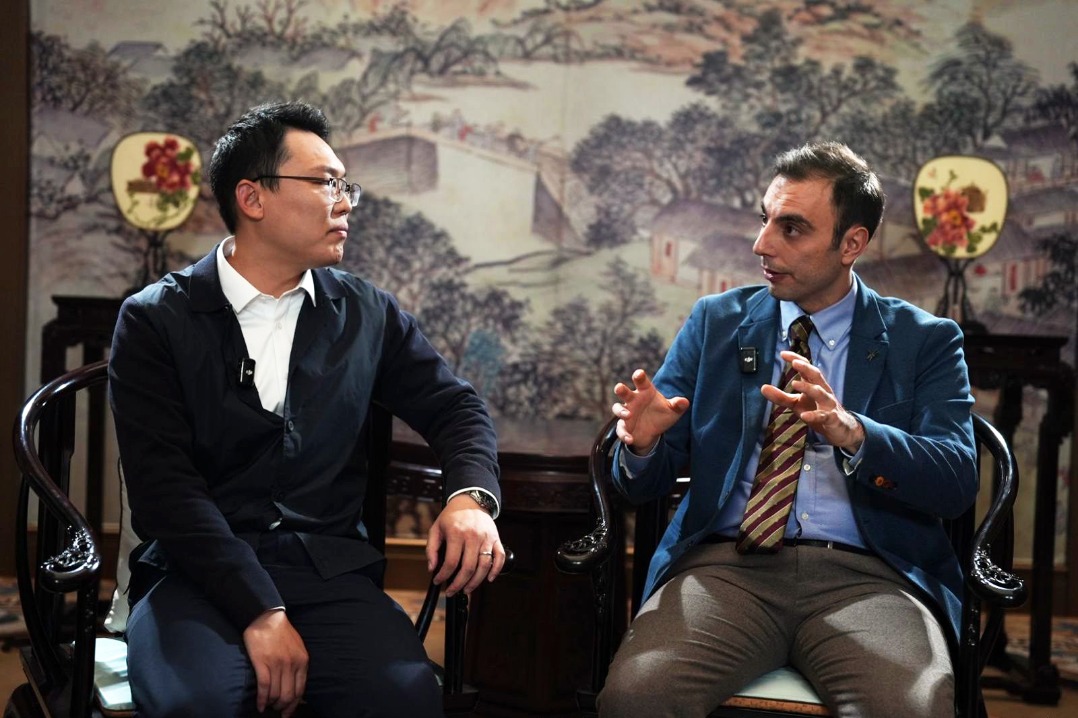

"Both civilizations embraced the notion of duality: light and dark, order and chaos, heaven and earth," says Xue. In China, this balance is captured in the I Ching, or Book of Changes, a Confucian classic dating to the 11th century BC. Rooted in the interplay of yin and yang, it reflects an early Chinese worldview in which existence was not fixed, but a fluid dance of opposites.

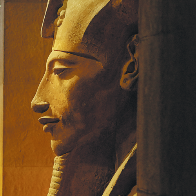

In Egypt, it could be glimpsed in the myth of Apep, the serpent of chaos, who battles Ra, the sun god, each night. Though Apep is vanquished each time, he returns, embodying the eternal struggle to uphold cosmic order.

Fittingly, 2025 in the traditional Chinese calendar is the Year of the Snake. In both cultures, serpents carried profound symbolic weight. On King Tutankhamun's golden mask, the cobra represents Wadjet, protector of Lower Egypt. After Egypt's unification around 3100 BC, Wadjet's cobra joined Nekhbet's vulture on the pharaonic crown, symbols of the unity of the two kingdoms.

Other serpentine deities included Renenutet, goddess of harvest, often shown with a cobra's head, guardian of granaries. The snake, close to the earth, symbolized fertility and the underworld, appearing in royal tombs to guide and protect the soul's journey beyond.