Layers of sacred reflections

Centuries of artistry turned the Mogao Caves into silent witnesses of China's unfolding cultural and political saga, Zhao Xu reports in Dunhuang, Gansu.

Vital crossroads

Among these regimes, the Xixia was established by the Tanguts, a historical ethnic group in China. Dunhuang's location, over 1,000 kilometers from the Chinese heartland and a vital stop along the ancient Silk Road made it both a cultural crossroads and a fiercely contested region among central and local authorities. This political complexity is vividly reflected in the grotto murals.

Take Cave 61, for example. Commissioned by Cao Yuanzhong, the de facto ruler of Dunhuang from 944 to 974, the cave features a wall dedicated to prominent women of the Cao family — including those married off and those who married into the family as part of political alliances with neighboring powers. Their identities and affiliations are distinguished by the varied styles of their headdresses.

"It takes a learned, discerning pair of eyes to discover all the hidden political messages," says Zhong, noting that when Cao appeared in a cave of another grotto complex about 100 km east of the Mogao Grottos, he chose to be depicted wearing a hat and robe seemingly borrowed directly from the royal wardrobe of a contemporary Northern Song (960-1127) emperor — rulers of the Chinese heartland at the time.

"The Cao family rulers of Dunhuang had consistently identified with and subscribed to the authority of the central Chinese dynasties," says Rong Xinjiang, a Silk Road scholar.

It's worth noting that a popular song, believed to have been performed during New Year celebrations in Dunhuang around the 9th or 10th century, opens with the line: "Hexi is the old land of the Han emperors".The Hexi Corridor — located in present-day Gansu province in northwestern China — is a vital stretch of the ancient Silk Road, at the western end of which Dunhuang lies. Here, the "Han emperors" refers to the establishment of the Dunhuang Commandery during the Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 220), several decades after the mission of Zhang Qian, the pioneering envoy who first charted the route in the first half of the 2nd century BC.

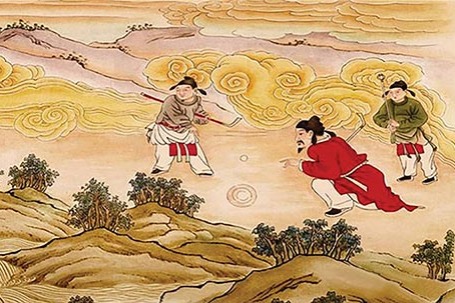

Dunhuang was officially incorporated into Tang territory in the late 7th century but fell to the expanding Tubo regime during Tang's internal turmoil in the late 8th century. Tubo control, lasting about half a century, began to crumble after the assassination of its last ruler in 842. Between 848 and 851, local strongman Zhang Yichao defeated the Tubo forces and reclaimed Dunhuang. Following his victory, Zhang immediately dispatched people to inform the Tang court that Dunhuang (then known as Shazhou) had been re-integrated into its territory.

Of the multiple delegations Zhang Yichao sent — some sources suggest there were as many as 10 — only one successfully reached Chang'an, the Tang capital. That mission was led by a Buddhist monk entrusted with the task by his mentor, the eminent monk Hongbian, a staunch supporter of Zhang Yichao, a devout Buddhist.

Today, a stucco statue of monk Hongbian presides over Cave 17 in Dunhuang. Tucked into the north wall off the entrance corridor to Cave 16 — the largest existing cave from the Tang Dynasty — Cave 17 measures no more than 6 square meters and yet, it is indisputably one of the most renowned Mogao caves. When it was first discovered in 1900, it was packed from floor to ceiling with more than 50,000 manuscripts, paintings and prints — earning it the title "The Library Cave" by which it is internationally known today. These materials form one of the largest repositories of religious, scientific and literary texts from the medieval period, offering invaluable insight into life in China and beyond. Today, they are housed in museums across Europe, North America and Asia.

A life-size statue representing Hongbian was originally discovered a few stories above Cave 17 and relocated to the cave in the 1980s after research revealed that it had always been intended to reside there.

Inside the statue, a small silk pouch containing Hongbian's ashes was found, along with official documents that attest to the statue's identity, says Zhong.

"These documents echo the content of a stone tablet embedded in one of Cave 17's walls, leading researchers to believe that the statue must have been removed from the cave at some point to make room for the manuscripts, while the stone tablet remained behind," she says.