A Party member's life condensed in 12 ledger books

From cigarettes to bicycles, Shanxi writer offers a glimpse into life in last century

When Liu Tao, a writer and photographer in North China's Shanxi province, perused a secondhand book fair one weekend in 2015, a bundle of 12 small notebooks caught his eye.

"I collect old items, not to lock them in dusty cupboards, but to research and learn the stories behind them," Liu wrote later in memory of that day. "I was rather interested in these little notebooks because they were the daily financial records of a family across a time span of 41 years, from July 1952 to May 1993."

When the shop owner named a price as high as 800 yuan ($111), almost 20 times the price of new notebooks of the same size and quality, Liu didn't bat an eyelid and bought them.

"I liked them and I knew their value," he said. "I only regret not having purchased more materials because I had to spend more time finding the details of that time in history later for my research."

From the 12 notebooks, Liu was able to glean intimate details about the daily transactions made over a 41-year period in the daily life of Zhang Jianmin, a Party official in Shanxi.

What he discovered was so fascinating that Liu put it all into a book titled The Financial Records of Jianmin: 1952-1993, The Digital Life of an Old Communist Party of China Member, which was published in August last year.

Cigarette brands

"Income and consumption records provide much information," Liu said. "They show us how the man lived, what he bought for daily use, as well as what he ate and drank."

For example, Zhang recorded every packet of cigarettes he bought, including its price, size and brand. A glimpse at the 41 years shows at least 40 brands of cigarettes that Zhang smoked, varying from decade to decade. In the 1950s, he smoked the brands Daqianmen and Sanmenxia. In the 1960s, he smoked a brand named Shanghai, switching to a brand called Albania in 1968. Later, he would go on to roll his own cigarettes.

Clearly a different era than today, but the brands he smoked actually reflected achievements and trends across China at those times.

In 1957, the Sanmenxia Dam on the Yellow River started construction and was put into use four years later. In the 1950s and 60s, Shanghai's role as the industrial base of the nation was so significant that many brands carrying its name emerged, including the bicycle, the watch and the cigarette.

The Albania brand was actually not a brand but mistaken for one because China imported a large number of cigarettes from the nation in the late 1960s, which were so popular that many people rushed to buy them.

In the 1970s, among Zhang's records were purchases of rolling tobacco, something commonly associated with those in economic difficulty due to its cheaper cost.

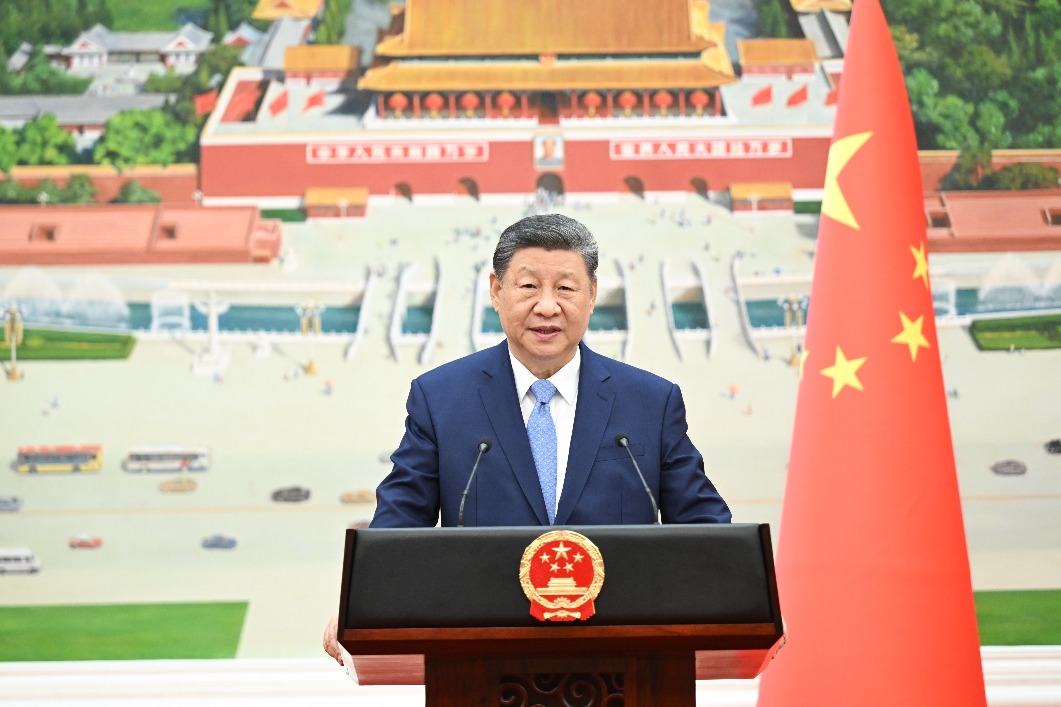

"It's noticeable that he only smoked the relatively cheap cigarettes," said Liu. "Zhang once served a position at the vice-provincial level, which is a quite high rank in the bureaucratic system, yet he had been leading a simple life in a virtuous way."

Riding the times

The nominal figures in Zhang's records reduced dramatically from 1955 onward, after the government introduced currency reforms to bring down prices. More currency reforms followed in 1962 and 1987.

Other details included the first sum of money Zhang spent on buying a bicycle, which was considered a luxury in China in 1964. For the bicycle, he paid 194 yuan — more than two-thirds of his family's monthly income at that time.

Interestingly, as a senior Party official, he had already been assigned the usage of a bicycle as early as 1953, during which time bicycles were even scarcer. Despite this, Zhang didn't know how to ride it at the time and in due course returned it.

It was small actions such as this that drew Li Chunlan, a writer based in the Shanxi capital Taiyuan, to conclude in a review in Taiyuan Daily: "The notebooks are more than the personal financial accounts of Zhang Jianmin. They are also part of the collective memory of that decade, the depiction of a longtime Party member, as well as the history of the local society from an ordinary person's angle."

Cold history, living memory

It wasn't easy sifting through the 12 notebooks to discover these stories.

Liu spent eight years, from 2015 to 2023, reading them carefully. The first year, he typed them all out — roughly 400,000 words — and sorted them into different categories. The following two years, from 2016 to 2018, he honed in on the financial records, comparing them with other materials, including the notebooks of other Shanxi officials.

At the end of 2018, Liu realized that he needed to contact Zhang's family to find out more and to gain consent for publishing things that might concern his privacy.

Judging from the dates of births of Zhang's children as recorded in the 12 notebooks, the oldest daughter among his nine children was already 70 years old, while his youngest son was 59.

Finally, Liu caught up with Zhang Yankui, Zhang Jianmin's fifth son, who often appeared in the medical bills of his financial records during his early childhood in the 1960s.

All of Zhang's children who were contacted consented to Liu's request to publish details of the old notebooks.

Upon its publication last year, the book attracted much attention and was subsequently named to the annual Top 10 Books of Social Sciences Academic Press.

"History is cold, but memories are alive," wrote Cai Hui, a history writer and book reviewer after reading Liu's book. "It's the memories that link the individuals with the grand history. By checking the time-honored financial records, the book has provided a unique microscopic angle from individuals, which is so interesting as to provide more possibilities about history."

In the preface to his book, Liu cited French philosopher and sociologist Henri Lefebvre, who wrote in his analysis Critique of Everyday Life that "the simplest event — a woman buying a pound of sugar — must be analyzed".

"Compared to that pound of sugar, Jianmin's financial records are precious treasure of a whole age."