Remembering China's merchant navy heroes

Despite their sacrifices, many seamen in Liverpool were forcibly repatriated

Editor's note: Thousands of Chinese merchant sailors risked everything to keep Britain's vital supply lines open during World War II. And yet, after peace was restored, they were only repaid with gross injustice. This page looks at the startling truth and the poignant tale of brave seamen, familial tragedies, forgotten history and a community's quest for answers and dignity.

Around the Tower of London, there are sites and monuments that tell stories of the long history of the United Kingdom. But there is one that many people pass by without noticing.

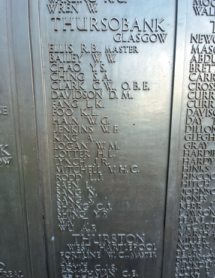

The Tower Hill Memorial on Trinity Square is a 20th century monument commemorating the 36,065 men and women of the merchant navy and fishing fleets lost at sea in both world wars, people who kept the country fed when it could easily have been starved into submission.

Unlike military campaigns, contributions of the merchant navy to the wartime narrative are rarely celebrated. And this has a strong Chinese connection, with an unexpected and unhappy ending.

In World War II, the main base of the merchant navy was the northwestern port city of Liverpool, which was part of the crucial North Atlantic supply route. The city's strong dock heritage meant it was also the site of Europe's first Chinatown.

The first recorded Chinese presence in Liverpool dates back to 1834, when the first vessel arrived directly from China, and a more significant community was established there in the 1860s, by Chinese sailors who worked for the locally based Blue Funnel shipping line, which sailed to Hong Kong and Shanghai.

With such numbers and specific skills, it is no surprise that in Britain's wartime hour of need, Chinese merchant sailors were quick to volunteer to serve their adopted homeland.

In what became known as the Battle of the Atlantic, an average of four convoys of supplies, each made up of as many as 60 ships, would come into Liverpool's docks each week, making it an artery of survival for the whole country, and an estimated 20,000 Chinese sailors helped keep it open.

However, at the war's end, many of Liverpool's Chinese merchant seamen were treated as an unwanted presence despite their service, sacrifice, and in many cases, longevity in the city, with some having married and had families.

Although plenty were happy to return home after such a grueling wartime experience, it is estimated that around 2,000 decommissioned sailors remained in the Liverpool area postwar. And soon after the end of the conflict in October 1945, a meeting took place involving officials from the Home Office, Foreign Office, Liverpool police, immigration inspectorate and others with one topic: getting rid of them.

The meeting resulted in the opening of a confidential file numbered HO 213/926 and titled "Compulsory repatriation of undesirable Chinese seamen", which remained out of the public gaze for decades.

Just a year earlier in 1944, the contributions of Chinese merchant sailors had been praised in the Ministry of Information's propaganda movie The Chinese in Wartime Britain, with the narrator saying "shoulder to shoulder in the greatest battle of naval history, alongside their British seamen comrades, they too brave the torpedoes and the bombs and the mines, making history under fire… life at sea fuels a unique spirit of comradeship between the men of all nations".

But unequal pay rates had for many years led to ill feelings and even violent confrontations with police. No sooner had the war ended than they became tired of being treated as cheap labor, and the fraternal feeling dried up.

Many were literally snatched off the streets and bundled out of the country, without a chance to say goodbye to the families they left behind, who were often mystified as to where they had gone, many going to their graves without ever having had an answer.

'Nakedly racist action'

Shortly after the documents were made public, Kim Johnson, the Labour Party member for the constituency of Liverpool, Riverside, raised the issue in a parliamentary debate in July 2021, in which she said it was one "of deep concern to both the long-established Chinese community in Liverpool and constituents of Liverpool, Riverside, as well as many communities across the country", before giving details of what she called "one of the most nakedly racist actions ever undertaken by the British government… a shameful stain on our history".

"We know that about 2,000 seamen were deported, snatched from their homes and their loved ones and dumped unceremoniously on the shores of a homeland that many had left decades before. Their families were never told what was happening; they were never given a chance to object, or even a chance to say goodbye," she said.

"Most of the Chinese seamen's British wives and partners went to their graves never knowing the truth, left to believe that their husbands had abandoned them along with their children, suffering immeasurable trauma from the actions of the British government."

John Belchem, author of Before the Windrush: Race Relations in 20th Century Liverpool, told the BBC that for many years, Liverpool's Chinese residents were regarded as "absolutely model migrants". But when the country was looking to rebuild, literally and metaphorically, after World War II, there was no place for them in what he called "a terrible piece of ingratitude", so excuses were found to eject them en masse.

"They were respectful, well-behaved, believed in education, weren't violent, looked after their wives, looked after their children," he wrote.

This underlines arguably the greatest tragedy of the affair. It was not just the injustice done to those taken away, but the equally large one done to the innocents left behind, including hundreds of children who grew up with no knowledge of what had happened to their fathers.

The story was covered in a recent podcast and documentary movie for History Hit TV, which featured Lucienne Loh, a reader in English literature at the University of Liverpool, who has been involved in raising awareness of the forced deportation story.

She told China Daily that there were a number of elements unique to Liverpool and its Chinese population that contributed to the incident, its consequences and the current revived interest.

"I first came across the story when I worked with members of the Chinese community on the story of their history in Liverpool, and one thing many of them had in common was a family link to the Blue Funnel line," she explained. "Its longevity and size means Liverpool's Anglo-Chinese community is unique in the UK, because of its extensive integration with the white British and Irish community, which is what first drew me to the story.

"As far as I know, the sailors weren't even necessarily returned to the ports or cities they came from, they were just dumped in the nearest colonial port, so overnight, people lost their fathers and husbands, with no idea where they'd gone.

"People often ask why the fathers didn't try to reconnect with their families, but a lot of the mothers didn't really want to draw attention to what had happened, or their children's ethnicity, so they often moved out to the suburbs and remarried, not drawing attention to the children's heritage, making any contact much harder."

The lost sailors are now commemorated with a memorial on the Pier Head in Liverpool docks, which honors "the many Chinese merchant seamen … required to leave … for their wives and partners who were left in ignorance… for the children who never knew their fathers… this is a small reminder of what took place. We hope nothing like it will ever happen again".

Keeping memory alive

But Loh said the 21st century Liverpool Chinese community is a very different demographic, and it is only the dwindling number of direct descendants who keep the flame of this memory alive.

"A large part of the Chinese community now is overseas Chinese students. The strata of the community affected by what happened after the war are now increasingly in their later years, so the story is kept alive by them, but they, and it, won't be around forever," she said.

"As for where this story leads, I suppose it depends who you speak to. Different people want different things. But I think most families just want answers — they want the dignity to grieve for their loss, which a lot of them have never had."

Today's Top News

- China to apply lower import tariff rates to unleash market potential

- China proves to be active and reliable mediator

- Three-party talks help to restore peace

- Huangyan coral reefs healthy, says report

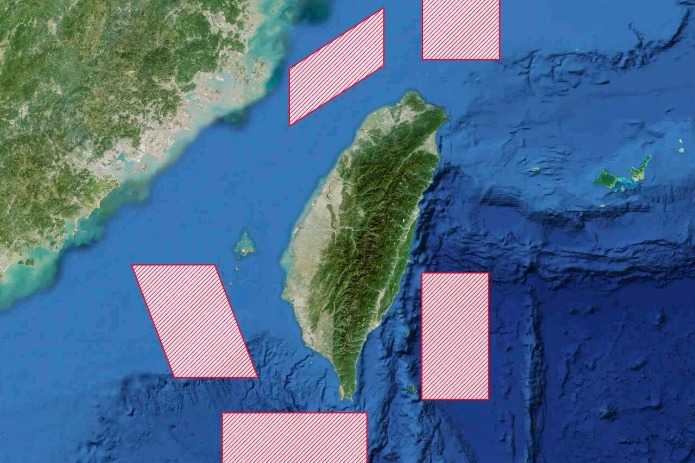

- PLA conducts major drill near Taiwan

- Washington should realize its interference in Taiwan question is a recipe it won't want to eat: China Daily editorial