Illustrator's cutting-edge ambition

Acclaimed author takes techniques used on paper from the distant past to inspire young readers and artists of today.

Illustrator Yu Rong sits in a lounge chair in her studio in the small village of Coton, near Cambridge, England, and contemplates her journey.

"If I hadn't gone back to Cambridge to have my babies, I think I would have done much better in the art industry," she says.

The studio is part of her house, where cherry trees, moonflowers, peonies, and lush greenery surround the backyard. It is the place where she transformed herself from a homemaker of 13 years to a cherished children's book illustrator.

During the past decade, Yu has made a name for herself by collaborating with leading authors in China and abroad, and publishing at least 20 picture books that have been sold in the United Kingdom, the United States, Italy, the Netherlands, Japan, South Korea, and elsewhere.

And she has won prizes and been shortlisted for awards, including one of the most prestigious in her field — the Yoto Carnegie Medal for Illustration, the UK's highest honor for children's literature.

Yu was already a phenomenon when she studied for her master's degree in the UK and, during her first year, had Walker Books, a mainstream British publisher of children's books, want to sign her. She was 28, and a student, but her first foray into paper-cutting for a school assignment had made a talent scout exclaim that it was an artistic expression that British people had not seen before.

Yu had not ventured into this traditional Chinese art form before that day, when the university department director asked all of the freshmen to make a piece that could best represent their background.

Paper-cutting popped into Yu's mind, and the encouragement she got from others drove her to explore it further.

"My affair with paper-cutting is an inadvertent one. Things growing in the gardens were never sown there. Despite that, when I pick up the scissors and colored paper, it doesn't feel foreign. Paper-cutting is a folk art that Chinese people are familiar with. So, perhaps, it has long been embedded in my mind," says Yu.

In 2000, when Yu graduated, she was invited to an exhibition at Sotheby's London. As soon as visitors entered the hall, they could see a representation of the silhouettes of the various people who may be in a museum, either standing in contemplation or whispering with companions, all cut from a long black sheet of paper. The work attracted many auction houses, galleries, and publishers that wanted to work with Yu.

Bringing down the curtain on her studies at the Royal College of Art, one of the most prestigious art universities in the world, and with a bright career ahead of her, Yu chose to move to Coton with her German husband, who teaches at Cambridge University.

In the small village 80 kilometers from the bustling capital, Yu gave birth to three children and wound up doing most of the housework. During the following 13 years, her busy home life contributed to the fact that she only managed to publish two books.

She says her publisher later told her: "If you hadn't gone to Cambridge, you would have been a paper-cutting queen by now."

But she says she valued her life as a homemaker and her identity as a wife and mother, and was happy to keep the house clean and tidy and take care of the needs of her husband and children, although, when she caught a glimpse of the colored paper, scissors, and pencils lying unused on the table, she struggled at times with worries that she should be creating more.

"I was so exhausted from achieving a balance between my career and housework. So I just gave it up," she says.

After 13 years passed in the blink of an eye, and at the age of 43, Yu, who had been "merely an ordinary housewife in Coton village and a middle-aged woman with a somewhat out-of-shape body", told herself, "It's time to think for myself."

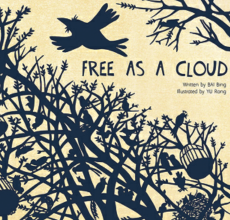

In the same year, she published Free As A Cloud in China, which tells the story of a myna bird that loses its desire to sing after being taken from the jungle and confined in a beautiful and spacious home.

The book's illustrations, in which extensive use of paper-cutting is employed, were described by publishers as appearing "out of the blue as an exceptional piece" at a time when children's picture books were not yet flourishing in China.

"Gains and losses vary from choices," Yu says, noting that her husband and children are her most loyal fans and supporters and that her love of children was what made her fully committed to being a children's illustrator.

Chinese roots

When pieces of paper of the same color are stacked together, the overlapping parts become darker. By following this technique, sheets of blue paper can, for example, vividly represent a pair of jeans. To add additional detail, Yu applies pencil, accentuating features, such as the folds in the fabric. That combination of paper-cutting and pencil drawing has formed Yu's unique style and is present in many of her works.

As a traditional Chinese art form, paper-cutting dates back around 2,000 years, to when Cai Lun, an official in the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220), improved paper making techniques.

By combining scissors and symbolic red paper, early Chinese paper-cutters were able to display a wide range of patterns, from a single image to symmetrical designs. Common motifs throughout time have included representations of harvests, animals, and mythical stories, which express Chinese people's gratitude for a good life, or hope for the future.

The art form requires skill to carve a simple piece of paper into an expressive scene, but the more Yu does it, the more inspired she feels. Whether she overlaps the paper, folds the pieces in half, carves the sheets, or adds pencil drawing later, her persistent practice often ends in new ideas.

Yu says she now enjoys playing with her tools, and she values the fact that paper-cutting has come to embody her cultural background as a Chinese person.

She grew up near a bamboo forest in East China's Jiangsu province but has been away from her hometown for 35 years. Despite that, Yu feels her bonds with China remain deep. "My roots are in China, and Chinese art always inspires me," she says.

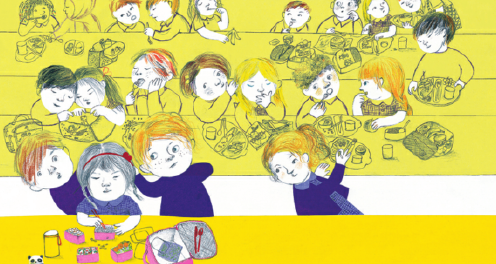

In Shu Lin's Grandpa, which tells the story of a girl who overcomes cultural differences and gains friendship after changing schools, a Chinese landscape painting was deliberately designed by Yu as the key to breaking the barriers the girl faced. In the book, students work together on an ink-wash painting, and while Shu Lin can use her brush freely, her friends only make a mess of the painting. With her help, the children grow to like their shy Chinese classmate.

"I would like to promote this particular form of Chinese art to my foreign young readers. Chinese landscape paintings allow for further imagination, as the artists won't depict the grand view in fine detail. So, when children go on a vacation in the Lake District, they may link the scenery there with the painting in Shu Lin's Grandpa. After all, mountains and rivers could exist in every country. Children may even choose to travel or study in China because of this picture when they grow up," Yu says.

The draw toward China in Shu Lin's Grandpa was Yu's "deliberate" design, but the inclusion of Chinese elements in her creations is "unconscious".

"They are kept in my inner drawer, which I pull open from time to time and use them," she says.

Yu has also set her heart on promoting authentic Chinese stories to global readers. The Visible Sounds, a collaboration with Chinese author Yin Jianling, is based on the childhood story of Tai Lihua, a deaf Chinese dancer. The book tells how the fictional Xiao Mi, who became deaf at the age of 2 because of illness, perceives sound through vibrations and, through her efforts, grows up to become a dancer.

Through the book, young readers have a chance to reach the world of people with disabilities, who may be a little different to them. The story of Xiao Mi originates from China and has found its way into the classrooms, libraries, and homes of Western countries, which has filled Yu with pride.

"Xiao Mi's story also belongs to the world. It could happen in every corner of every country," Yu points out.

She says the girl's resilience is a shared personality of mankind, which transcends language and cultural barriers.

"The fact that this book has been introduced to the UK and has been shortlisted by the Yoto Carnegie Medal for Illustration judges is an indication of the importance of diversity to human society today," she says.

"I used to only think of bringing out talent during my creation, instead of realizing that the human knowledge and affections, or the epitome of families and societies, would all be condensed in a book," says Yu.

From Shu Lin's Grandpa and The Visible Sounds to Yu's recently completed work on autistic children, she has increasingly dabbled in themes related to humanistic care.

A book is not simply a book

As in Shu Lin's Grandpa, Yu has also felt an uneasiness when facing a new environment, especially when she moved from school to school, following her mother, who was a primary school head teacher.

Later, when she moved to the UK, she was confronted with a society that was seen as a melting pot of racial and ethnic diversity, but that was also a place where the white community was in the majority. Reflections on conflicts, understanding, identification, and integration became part of her daily life.

She hopes her upcoming book on autistic children will be another growth spurt for her development.

"One of my friend's sons is autistic, and he is particularly interested in light," she says. "The boy caught the light by covering his eyes with the back of his hands and looking at it through his fingers. Now, if one day, I meet a child doing similar things on the street, I would know he or she is enjoying the most wonderful moment in life."

For children, these stories, word by word, stroke by stroke, can educate them to perceive the wider world with an inclusive mindset from an early age.

"That's the power of children's books," says Yu.

What makes her prouder still is that she is speaking up in the Western children's book industry, as a Chinese person and as an Asian woman.

Yu recalls being invited to the English city of Newcastle in 2018, to attend a forum called Diversity of Voice, where she met with others to discuss how to increase diversity in the children's book publishing industry. She was one of two Asians in the room and felt a little excited about the opportunity to represent Asians in the field.

That sense of responsibility pushes her forward.

"My work, and my identity, might also plant a small seed in the hearts of some people, and this seed must mean something," says Yu, who adds that one day, it may take root, sprout, and grow into a huge tree.

Zheng Wanyin contributed to this story.

Today's Top News

- China to implement zero-tariff policy for 53 African countries

- Xi sends congratulatory message to 39th African Union Summit

- China upgrades Xiong'an high-tech zone to national level

- Xi extends Chinese New Year greetings to ring in Year of Horse

- Country sees strong rebound in FDI

- Long March 10's booster retrieved from sea for 1st time