An essential medical guide

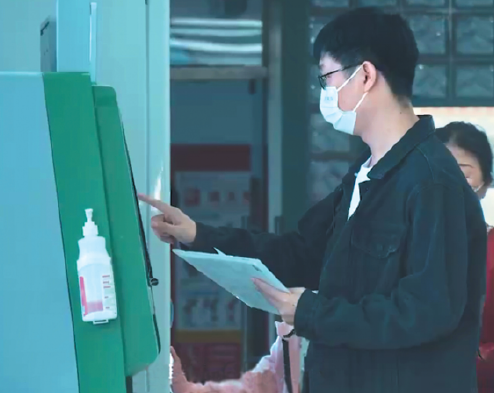

Beijing resident provides welcome assistance to patients facing unfamiliar and sometimes overwhelming hospital visits, Yang Feiyue reports.

Han Zheng strongly believes that more people are availing of outpatient services at hospitals across the capital following the Spring Festival holiday.

"Perhaps it's because the pandemic has passed, and many patients who postponed their hospital visits before are lining up for treatment," the Beijing resident says.

Han is in his mid 30s and started to work as a medical guide about 13 months ago after he found that many patients were struggling to find their way around hospitals.

"After the COVID-19 outbreak in Beijing in December, the respiration and internal medicine departments had been full to bursting, while the rest of the departments experienced that patients were thin on the ground," Han recalls.

He accompanied one of his patients to an emergency treatment in late December.

"She was one of my regular clients, and was suffering from an enduring pain in her lungs for half a month," Han says.

"The emergency room was crowded, and it took five hours for us to see the doctor, and another three hours to take the CT scan," he recalls, adding that it would have been about two hours to finish the whole process before.

Han kept his patient company the whole time and helped to make the wait easier.

The patient was in her 30s and was working and living alone in Beijing, with her family far away from her.

"Every now and then, she would have me run some errands for her at the hospital," Han says.

In December, the young woman and many of Han's patients would turn to him when they had trouble getting an appointment with the right doctors or simply didn't want to be alone at a hospital.

Han answered their calls after taking a weeklong rest after getting COVID himself at the beginning of December.

"Most of my orders during the period were from patients who I had dealt with before," he says, adding that some of them had left Beijing but still had unresolved problems, such as test results that had yet to come out.

"One patient from Henan (province) had his bone operation done in 2015, and needed me to find information on the steel nails used on him," Han explains.

Although it was quite a hassle finding the patient's doctor who had already retired and digging into the buried medical history, Han managed to deliver what the patient asked for.

"It felt good to help solve some emergencies for them," Han says.

Wearing two facial masks, he knows the hospital like the back of his hand, after more than a year of practice.

He usually takes two orders a day, one in the morning and the other in the afternoon, with each lasting at least one hour.

The costs range from 300-500 yuan ($44.3-$73.8), depending on the length of the service time.

Born in Chifeng, North China's Inner Mongolia autonomous region, Han was engaged in international trade for several years, before he started his own business in 2018.

The business didn't pan out, especially after the outbreak of the pandemic in 2019.

In the time of desperation, he came across the novel line of work while flipping through video-sharing platform Douyin.

"I was like I could do it, because I had been around my relatives and friends from home during their visits to hospitals," Han says.

Han did a little math in his head. With rich medical resources, Beijing has been a destination for patients from across the country with complex medical conditions.

He figured the elderly with chronic diseases and whose children could not always be around would appreciate his service.

There are 264 million people on the Chinese mainland who are 60 or older, accounting for 18.7 percent of the total population, according to the National Bureau of Statistics, and the number is expected to pass 300 million by 2025.

The number of frail seniors over the age of 60 who experience difficulty in performing everyday tasks passed 42 million in 2020, according to the National Working Commission on Aging, meaning that one in six people who were 60 or older were unable to take care of themselves.

Han was also encouraged by the country's move to address the needs of the aging population, as the State Council has released a development plan for China's elderly care services during the 14th Five-Year Plan period (2021-25).

The plan specifies major goals and tasks, including expanding the supply of elderly care services, improving health support for seniors, and advancing the innovative and integrated development of service models.

In addition, he thought he could be of some assistance to patients from outside Beijing who are not familiar with the medical system in the capital.

Han opened an account on Douyin, with his name and identity card's photo.

"You have to show your true information to earn the trust of potential clients," he explains.

Han also advertised his English and Arabic language skills for international patients.

Then, he got down to studying hospitals, such as their specializations and medical treatment procedures for different diseases.

"It was to save time for patients, and answer their questions," Han says.

At the beginning, he was caught off guard when people started to approach him with questions.

It prompted him to read up on information on common medical problems and make connections with pertinent hospitals.

"If I had to go to a new hospital, I would visit beforehand to familiarize myself with its treatment process and the locations of all departments and examination rooms," he says.

He would also acquire details about patient conditions, which he would study before offering suggestions.

"Now I can immediately offer them two to three public hospitals once they tell me their problems," Han says.

In July, Han shared on his Douyin account a video of parents at the Beijing Children's Hospital, Capital Medical University, in the middle of the night. It received more than 130,000 views, which got more attention to his business.

As his dealings with patients increased, Han has come to see the value of his work.

He watched firsthand how a parent was struggling to take care of a sick child while fumbling around a big hospital.

"I felt my work was worth it whenever I could save them some procedural trouble, such as pre-diagnosis consultation, medical report and medication pickups," he says.

Han says he can feel the evident rise of the career, as there are now at least thousands of medical guides, as opposed to only dozens when he started.

As an emerging career, medical guidance has yet to have an agreed set of standards for safety and sustainable development.

"There is a lot at stake, such as what if the client withholds some information, such as an infectious disease or some accidents happened to patients in their old age," Han asks.

"It now all depends on the honor of the clients."

Wang Hui, an operation manager of a medical guide service company in Hefei, Anhui province, believes the intelligent medical services can be difficult for some elderly people when seeking medical treatment.

Changes in family structure and the accelerating aging of the population, as well as the increasing need for better medical treatment in first-tier cities have increased demand for medical guide services, according to Wang.

Song Yu, a research assistant at the Institute of Sociology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, says the demand for these services is real, and hospitals have set up guide desks or provided guidance for newly admitted patients.

Song suggests medical service facilities offer professional training to related personnel to strengthen management and help avoid conflicts between medical guides and patients.

Wang Yunfei, associate professor at Anhui University's School of Sociology and Political Science, urges authorities to issue guiding documents to regulate the entry threshold, medical guide service content and fees.

Wang Yunfei also recommends both parties sign a contract to clarify their rights and obligations.

Being a medical guide has exposed Han to some of his customers' weakest moments, when they went through pain and life-or-death choices and faced pressure and had to deal with their fate.

Some patients might have a panic attack and can't make sense of the doctor's words, so Han has to comfort them like family while noting down the diagnosis.

Some young people have to work and can't make time to go to the hospital to get their test results, and therefore seek Han's service.

When Han gets some bad medical reports for his customers, he has to think of ways to cushion the blow and propose suggestions before making the dreaded call.

Speaking about his future plans, Han says he would stick it out and continue to reach out more to those who need him.

In September, the Beijing Municipal Health Commission asked him to take part in a survey on the development of the medical-guide sector.

"It might be a sign of the country standardizing the profession, and that will be good news," he says.

Today's Top News

- Pragmatic discussions can illuminate the way to a brighter future for China-EU ties

- Ruling parties suffer major defeat in Japan's upper house election

- China, EU to hold 25th China-EU Summit in Beijing

- China's records growth in internet users and AI technology

- Japan's ruling coalition loses majority in both parliament houses

- Mega-hydro project launched in Xizang