Ghosts keep spirit of Dickens alive

Exhibition focuses on literary great's supernatural leanings, Julian Shea reports in London.

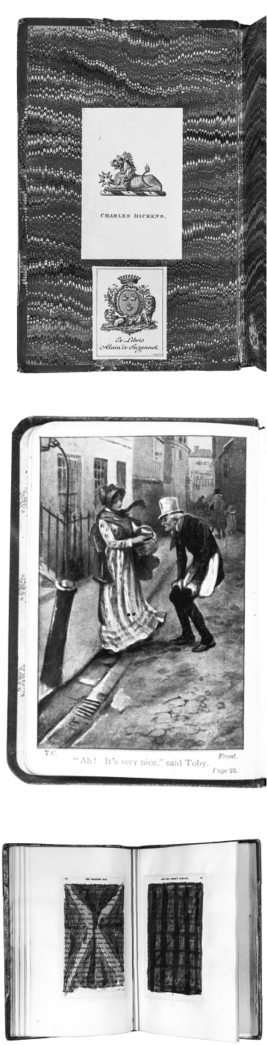

English writer Charles Dickens created some of the most famous fictional figures in world literature, such as Oliver Twist, David Copperfield, Miss Havisham and Ebeneezer Scrooge, and more than 150 years after his death in 1870, his work remains as popular as ever.

Never out of print and translated into countless languages, Dickens' work still captivates readers around the world, including in China.

An article in the September 1999 edition of the scholarly publication Dickens Quarterly mentions that the first translations of his novels appeared in China in the 1900s. Just over a century later, in 2012, Zhejiang Gongshang University Press produced the first translation of Dickens' complete works — novels, short stories, essays and all.

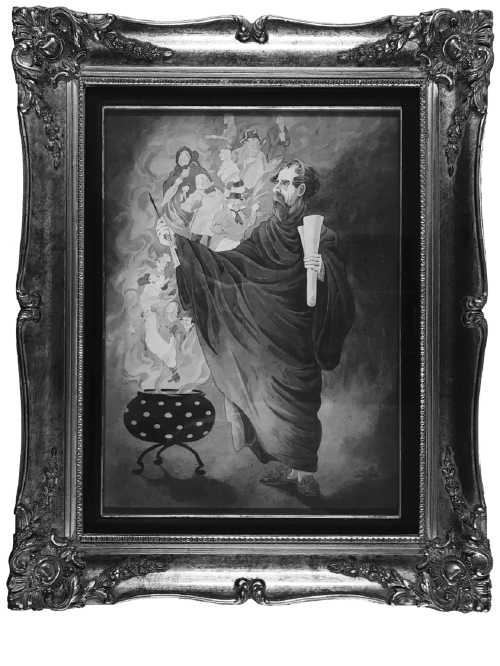

A new exhibition at the Charles Dickens Museum in London, entitled To Be Read at Dusk: Dickens, Ghosts and the Supernatural, which runs through March 5, 2023, focuses not so much on the unforgettable people into which Dickens breathed life, but the less tangible world of spirits and ghosts, a subject that was hugely popular when he was writing, and which ran as a thread through much of his work.

From The Pickwick Papers in 1836 to the unfinished Mystery of Edwin Drood in 1870, Dickens wrote 15 novels, as well as huge numbers of novellas — most famously A Christmas Carol, in 1843 — short stories and magazine articles, many of which have a ghostly presence, reflecting contemporary fashions.

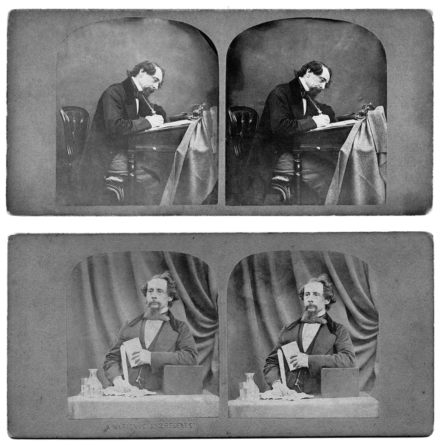

"Dickens is a fantastic gateway to many different aspects of life and culture of his time," Frankie Kubicki, senior curator at the Charles Dickens Museum, says.

"His characters are so lifelike, and drawn from across all areas of society, that they speak to all audiences. In his lifetime, he was a huge star, with mass global popularity. He drew huge crowds wherever he went, and it even got to the point where he didn't like to get his hair cut because he knew people would want a lock of his hair."

In 1846, seances, gatherings where people called "mediums "claimed to be able to make contact with the spirit world, received the royal seal of approval when Queen Victoria attended one. In 1862, the first lady of the United States, Mary Lincoln, held one at the White House, so it was inevitable that a writer with such an observant eye and curious imagination as Dickens should find inspiration there. But, as the exhibition, which features an exhibit entitled A Fascinated Sceptic explains, he was never drawn in by it.

"Because of sad factors like child mortality (two of his seven siblings died in infancy), there was a different relationship with death and loss in those days," Kubicki explains.

"Dickens knew stories about the spirits were popular, and he enjoyed writing and performing them because of the power they gave him over an audience. There's a letter he wrote to his wife, about a reading he gave of his 1844 work The Chimes, where he talks about how much he enjoyed that feeling.

"But although he kept his mind open because he loved storytelling, Dickens was very much against people exploiting those who were grieving, and the older he got, the more vocal he was in speaking up against these types of fraudsters."

Dickens' views on the subject may have been hardened by an experience in June 1865, when a train he was on was involved in a fatal accident at Staplehurst in Kent. He tended the injured and dying, later writing of the trauma he suffered as a consequence — an incident touched upon at the exhibition.

The display also includes some of the original pencil sketches of the ghosts in A Christmas Carol, which remains one of the most popular works in literary history, the subject of innumerable adaptations, remakes and reimaginings, and an integral part of the culture of Christmas around the world.

But, despite it earning Dickens the nickname of the man who invented Christmas, it is a ghost story, about the miserly Scrooge being visited on Christmas Eve by three spirits who remind him of his past, enlighten him on his present, and warn him of his future, causing him to change his life and embrace the spirit of generosity. This, says Kubicki, shows the elusive nature of his ghostly writings.

"What we're trying to show in the exhibition is that spirits and specters crop up in his writing beyond just the well-known ghost stories," Kubicki says. "It starts with The Pickwick Papers, where they are in a story within a story, as people tell tales about ghosts, while the most references to ghosts crop up in Bleak House, which is about a long-running legal dispute, so it's not actually a ghost story.

"For that reason, it's hard to say exactly how many ghost stories Dickens wrote, but it's probably around 20."

However many there may be, the ghosts in the works of Dickens helped make his name, and continue to leave their imprint on popular culture.

So, ironically, it is the fictional spirits that the fascinated skeptic created that have ended up playing a role in keeping his name and reputation alive.

"Not only has Dickens been a huge inspiration for so many authors who came after him, but even when you look at the popular image of what ghosts look like today, very often they look like the ones from A Christmas Carol," says Kubicki.

"That's a lasting impact."

Today's Top News

- China's industrial profits down 1.8% in H1

- Thailand responds to Trump's ceasefire call

- Recall vote shows DPP's manipulation runs against Taiwan people's will: mainland spokesperson

- Top DPRK leader visits China-DPRK Friendship Tower

- China proposes global cooperation body on AI

- Scholars propose inclusive human rights framework