Sustainable development a matter of market design

Southeast Asia's Malay Archipelago is very far away from Ukraine, and the indigenous people of Borneo - living in some of the most pristine jungles left in the world - do not leave much of a carbon footprint. Yet even they cannot escape the effects of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, inflation and climate change.

In addition, one of our best hopes for building a better world - the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, or SDGs - is looking increasingly unattainable.

The SDGs are supposed to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure prosperity for all by 2030. But the latest SDG report makes for grim reading.

"Cascading and interlinked global crises" - including the COVID-19 pandemic, global warming, conflict, inflation and polarization - are jeopardizing the SDG agenda, having already reversed years of progress toward eradicating poverty and hunger.

Our recent visit to Borneo highlighted the consequences of these failures for indigenous people. Most of the 112,000 Murut people live in barely developed rural areas in the island's northern inland regions - mostly in Sabah, Malaysia - where goods and people used to move either by river or along gravel roads.

A generation ago-after living for centuries as hunter-gatherers, dependent on the forests - the Murut were persuaded to move to settlements and farmland they were given. But prices for their primary products - unprocessed rubber - have fallen, squeezing their incomes, and they have neither the capital nor the know-how to shift to more profitable crops, such as fruits or vegetables.

Improving the lot of Sabah's indigenous population will require the development of business models that are both profitable and sustainable and will enable communities to avoid excessive dependence on aid and subsidies. These models must be built on indigenous knowledge of local land and ecosystems, and be supported by investment in infrastructure and appropriate regulation.

As a 2021 book edited by Jan Wouter Vasbinder and Jonathan Y.H. Sim showed, the world is not wanting for powerful technologies, funding, talent or know-how. The fact that these factors are not driving rapid progress toward the SDGs is a failure of governance - in particular, of market design.

Part of the problem is the lack of systems for matching the supply of technology, knowledge and funding with demand. In theory, the internet "flattens" access to information, know-how and even finance. But rural indigenous people often do not have electricity, let alone internet access, so even where they have valuable expertise and ideas, their ability to get the support they need is severely limited.

The development of "smart villages" could help. Such villages would have access to high-quality services - water, energy, transportation and connectivity - and be linked to smart cities. This would improve food security, spur ecotourism, foster entrepreneurship and enable innovative rural-urban partnerships in critical areas like adaptation to climate change.

Businesses can play a central role in developing such villages, under the mantle of corporate social responsibility. But they would still need a way to determine where to direct their resources to do the most good. This demands government-led efforts to design and implement a social-enterprise market.

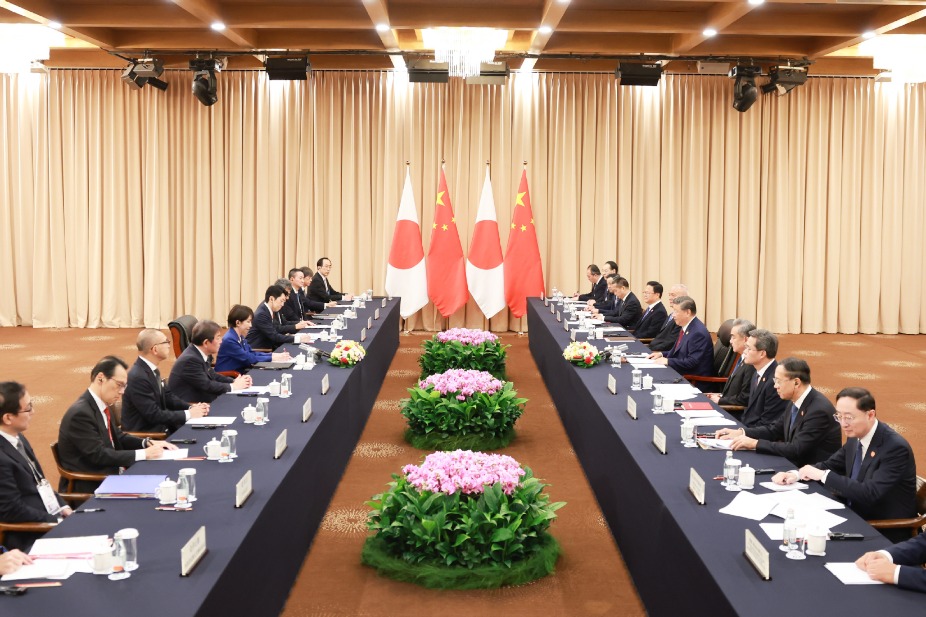

The challenge is not limited to matching supply and demand. As China's experience eradicating poverty shows, complex systems change requires top-down coordination and planning that accounts for - and responds to - bottom-up feedback. (This approach will be central to China's own rural vitalization, including agricultural upgrading, land regeneration and expanded educational and employment opportunities.) As UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres put it, achieving the SDGs will require global, local and people-level actions.

At the same time, governments must "nudge" complex social systems into alignment with sustainable-development objectives, using tax and regulatory incentives.

Regulation would certainly help address two other key challenges facing Borneo's indigenous communities. First, palm oil estates have eroded the forest cover and poisoned local waterways with pesticides and fertilizers, leaving rivers yellow with iron-and aluminum-rich laterite soil erosion, unsafe for drinking and depleted of fish. Second, the Pan Borneo Highway that cuts through the jungle, while making transportation easier, has disrupted local ecosystems and spurred young people to leave in search of jobs.

High-level objectives like the SDGs cannot be achieved with rigid, one-dimensional approaches. Instead, they must be translated into well-coordinated, concrete initiatives that can be implemented and adapted at the grassroots level. This will be possible only with the right market structures and incentives, overseen by a genuinely responsive regulatory apparatus.

Andrew Sheng, a distinguished fellow at the Asia Global Institute at the University of Hong Kong, is a member of the UNEP Advisory Council on Sustainable Finance. Xiao Geng, chairman of the Hong Kong Institution for International Finance, is a professor and director of the Institute of Policy and Practice at The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China daily.