Shanghai refugee book author honored

Writer recognized for highlighting the role city played in providing shelter to Jewish people, Zhang Kun reports in Shanghai.

An author of a book highlighting Shanghai's role in providing refuge and looking after Jewish wartime refugees has won a major honor.

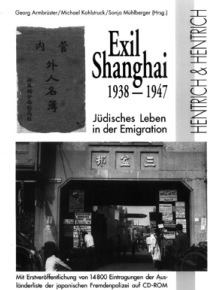

More than 400 babies were born to Jewish refugee parents in Shanghai during World War II. The unique childhood experience of these "Shanghai babies" made such an impact on their lives that one of them, Sonja Muehlberger, committed herself to researching Jewish refugees in China.

Muehlberger is 83 and lives in Berlin. She has spent decades building a database of Jewish refugees in Shanghai. The efforts developed into the Wall of Names of Jewish Refugees in Shanghai during the 1930s and '40s, a permanent installation at the Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum.

On May 31, Muehlberger was the recipient of the honorary title of Ambassador of Silk Road Friendship along with 11 others. The online event, the second such ceremony, was jointly hosted by the China International Culture Exchange Center and Global People, a magazine affiliated to People's Daily, to present stories of friendship between China and countries involved in the Belt and Road Initiative, and spread a message of peace and solidarity between nations.

The book, Exil Shanghai 1938-1947, co-authored by Muehlberger, Georg Armbruester and Michael Kohlstruck, was published in 2000.

"Muehlberger committed herself to the studying and recording of Jewish history in Shanghai, telling the stories of passionate and friendly Chinese people," say the event's organizers. "As a member of the Jewish exiles in Shanghai, she witnessed the darkest moment in the 20th century. When the Jewish exiles had their most difficult period, Chinese people selflessly extended their helping hand. This illustrates the idea of building a community with a shared future for mankind, a value deeply rooted in traditional Chinese culture… from that difficult time to the close ties of today, we have seen the seeds of friendship blooming into flowers of peace."

In 2019, Muehlberger was also awarded the Federal Cross of Merit by the German president because of her outstanding contributions to the preservation of the history of the Holocaust.

There have been debates in the academic world over the narrative about Jewish exiles in China, and the exact number during World War II, says Chen Jian, director of Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum, explaining the importance of the installation of the wall of names. Real people with names that can be tracked down are solid evidence that tells the truth.

Chen was impressed by the extraordinary energy of Muehlberger, and he told the media about the close ties she had with the museum. "Over the years, she has collaborated with the museum, and she is the leading contributor to the list of names inscribed on the wall," he says. "She is keeping on with the work, and the number is still growing."

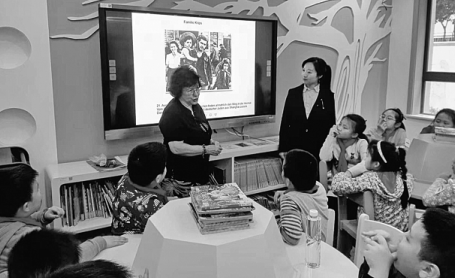

As a teacher, writer and lecturer, Muehlberger has been telling the stories of how more than 20,000 Jewish refugees found a home in Shanghai. It is important to keep telling them, because "new Nazis are emerging, and it is necessary to stand up to them," she said during an online conference with the media in Shanghai.

In 2014, when the wall was first established in the museum, there were more than 13,000 names, and in 2020, when the museum was refurbished and the wall rebuilt, the names had increased to 18,578, Chen says. The number keeps growing, Muehlberger explained, "because we still have information coming in from all over the world".

Her parents Hermann and Ilse Krips met each other in Frankfurt. In 1938, Hermann Krips was sent to the Dachau concentration camp for four weeks, until Ilse got him released by obtaining exit papers. In March 1939, they boarded one of the last ships to take refugees to Shanghai, arriving in the city in April. Sonja was born six months later.

All through the rest of his life, her father "never forgot how people were reduced to numbers in the camp," said Muehlberger. "He believed people should be named."

She showed her birth certificate, on which she was identified as "Baby Krips". Three months later, her father went to the German Consulate General in Shanghai, to get her passport. Hermann was well aware of the threat posed by the Nazi government, but he was determined to get a passport for the baby girl, Muehlberger said. They named her after Sonja Henie, a three-time Olympic gold medal-winning figure skater and film star from Norway.

Growing up in the Hongkou Ghetto, an area designated for Jewish people by the Japanese occupiers, Sonja was a lively girl who "never forgot anything". She recalled her mother reading her the German fairy tale of Snow White. When it snowed one day, her father gathered the snow from the roof and put it in a basin, so that she could play with it. A lot of historical documents were kept in the family, such as her parents' boat tickets to Shanghai, her vaccination card and other items, which all became important elements for her book.

Her brother was only 2 when they left Shanghai in 1947, and he once asked about his sister's passion for Shanghai and China. Still calling herself a Shanghainese, and considering it her birth home, Muehlberger made altogether nine trips back to the city since 1998.

Her childhood in Shanghai gave her an open personality, ready to engage with people from other cultures. She recalled with excitement the first time she saw Chinese people after the family moved to Berlin. It was in 1951 and a Chinese delegation of children participated in the World Youth and Students Festival there. She made friends with the Chinese Young Pioneers of her age, and they exchanged red scarves.