Falling fertility rates reshaping outlook around the world

Countries from Asia to Europe look to various methods to adapt to changing demographics

People throughout Europe can undoubtedly recall a giant inflatable baby wearing a slogan T-shirt floating around. The 7-meter-high mascot has been in London, Glasgow and countless other locations as part of a global campaign by Population Matters, a UK-based charity that addresses the problem of overpopulation.

On their website, a big screen is used to show the current total world population growing with every second. "Our population has become so large that the Earth is struggling to cope. Right now, we are still adding more than 80 million people a year," the group states below the growing number of more than 7.9 billion.

It is true that the world population is still growing, however, the problem that the majority of the world is concerned about is the total opposite: declining birthrates in both developing and developed countries.

In a recent announcement, Tesla CEO Elon Musk shone a spotlight on Japan's declining population by saying that the world's third-largest economy will "cease to exist" if low birthrates continue.

"At the risk of stating the obvious, unless something changes to cause the birthrate to exceed the death rate, Japan will eventually cease to exist. This would be a great loss for the world," Musk said on Twitter, commenting on the fact that Japan's population fell by 644,000 in 2021, its largest drop on record.

While there is nothing new about Japan's population decline, given that 2021 marked the eleventh consecutive year that the population has decreased in the country. The tweet nevertheless caused a stir, pointing to the fact that the world is ill-prepared for the global fertility bust.

Globally, fertility rates are used to measure the average number of babies a woman is projected to have over her lifetime. Demographers say that if the number falls below 2.1, the size of a population will start to fall, meaning a country's population can only grow without net inward migration if couples have at least 2.1 children on average. And that number should be higher in order to maintain replacement in nations where childhood mortality is high.

Across the world, although some countries continue to see their population grow, especially in Africa, population stagnation and a declining fertility rate are occurring almost everywhere else: Ghost villages appearing in Japan and maternity wards are shutting down in China and Italy. South Korean universities are having a hard time finding enough students and thousands of houses were razed in Germany to build parks.

According to a United Nations report, World Fertility and Family Planning 2020, total fertility has fallen markedly over recent decades in many countries, resulting in close to half of all people globally living in a country or area today where lifetime fertility is below 2.1, and the global fertility rate declined from 3.2 live births per woman in 1990 to 2.5 in 2019.

The report said even places with the highest fertility levels are seeing a decline as sub-Saharan Africa's total fertility fell from 6.3 births per woman in 1990 to 4.6 in 2019.

Niger tops list

In fact, the vast majority of countries with the highest fertility rates are in Africa. Niger tops that list at 6.8 children per woman, followed by Somalia at 6.0 and the Democratic Republic of the Congo at 5.8. The North African country of Tunisia has the lowest fertility rate on the continent at 2.2. But even this, the lowest rate in Africa, rests roughly in the middle of the global list of more than 200 countries and territories.

Another Jaw-dropping study in 2020 by researchers from the University of Washington's Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation showed that women in 1950 had an average of 4.7 children in their lifetime but in 2017, the global fertility rate nearly halved to 2.4 and the study predicts it will further fall below 1.7 by 2100.

The United States fertility rate will decline from 1.8 in 2017 to 1.5 in 2100, with China, the most populous country, seeing a fall in its population from 1.4 billion in 2017 to 732 million in 2100 and the population of India, the second largest in the world, would set to hover around 1.09 billion in 2100, according to the study.

By then, the researchers said fertility rates in 183 of 195 countries in the world, will not be high enough to maintain current populations, adding that Japan, Thailand, Italy and Spain are among the 23 countries seeing populations shrink by more than 50 percent over the same time frame.

"The last time that global population declined was in the mid-14th century, due to the Black Plague. If our forecast is correct, it will be the first time population decline is driven by fertility decline, as opposed to events such as a pandemic or famine," Stein Emil Vollset, lead author of the study said.

Environment enthusiasts argue that a population decline could ease pressure on natural resources, help to curb the impact of climate change and free more women from household burdens and macroeconomists said reductions in fertility enhance economic growth as a result of reduced youth dependency and an increased number of women participating in paid labor in the short term, but demographers say that it also invites all the negative consequences of an inverted age structure in the long run, meaning there will be more old people than young in society.

"The structure threatens to upend how our societies are organized," said Yu Qiang, a professor at Beijing Technology and Business University, "We assume that in a society, a surplus of young people will drive economic growth and pay for the healthcare of the elderly. But that concept needs to be changed when countries learn to live with a population decrease. Along with it, a lot of things we are now familiar with will have to be changed like the streets, the houses, the offices, the way of traffic and our idea of consumption and retiring."

Nineteenth-century French philosopher Auguste Comte said, "demography is destiny", and that claim seems more persuasive today as population trends are increasingly recognized as the strongest forces in economics, affecting global prosperity, the growth of individual nations and the strength of public finances.

The World Economic Forum said the consequences of world population decline are severe as there were six people of working age for every retired person in the 1960s, but there are only three-to-one now and by 2035, it will only be two-to-one.

In an article published on WEF's website, Darrell Bricker, CEO of the public opinion research firm IPSOS Public Affairs, argued that "Some say we must learn to curb our obsession with growth, to become less consumer-obsessed, to learn to manage with a smaller population. That sounds very attractive. But who will buy the stuff you sell? Who will pay for your healthcare and pension when you get old? Because soon, humanity will be a lot smaller and older than it is today."

Bricker also predicts that the global population of over-80s will be up 148 percent in 50 years but the working population will be up only 2 percent.

As scary as it sounds falling fertility rates are a success story in many ways.

According to the World Population Review, three main factors have been credited for a decrease in the global fertility rate: fewer deaths in childhood, greater access to contraception, and more women getting an education and seeking to establish their careers before-and sometimes instead of-having a family.

A paper published in Economics of Education Review in 2022 by Chen Jiwei and Guo Jiangying from Nanjing Agricultural University further proved the idea by analyzing the relationship between female education and the fertility rate in China after the country conducted its compulsory schooling reform.

"Our estimates show that an additional year of female education significantly reduces the number of births by 0.24," said Chen and Guo in their paper, adding that "the negative impact of women's education on fertility operates by reducing the number of children per woman rather than increasing the incidence of childlessness."

A research paper, from Keio University in Japan, in 2022 by Cyrus Ghaznavi, Takayuki Kawashima and others found that the COVID-19 pandemic also negatively affected people's willingness to have children.

Impact of pandemic

"Marriages and divorces declined during the pandemic in Japan, especially during a state of emergency declarations. There were decreased births between December 2020 and February 2021, approximately 8 to 10 months after the first state of emergency, suggesting that couples altered their pregnancy intention in response to the pandemic. Metropolitan regions were more affected by the pandemic than their less metropolitan counterparts," the research said.

To handle the deteriorating situation, countries have taken various approaches. In 2020, South Korea paid every pregnant woman approximately $500 for helping the country address its dire demographic crunch, and that number has increased to $1,700 now. Countries like Sweden and Japan have sought to boost the birthrate by introducing better parental leave, state-provided child care and stronger reemployment rights. Others like Canada have expressly set out to offset aging populations and low birthrates by immigration intake.

However, all those policies tend to have a limited impact as fertility rates are still falling rapidly across the rich world.

In their 2019 book Empty Planet: The Shock of Global Population Decline, Bricker and John Ibbitson argue that developed countries can emulate Japan, which has tried and failed to boost the birthrate through various noncoercive measures and yet maintains strict limits on migration, even as the dearth of young people drags down growth and reshapes society in momentous and hard-to-measure ways because an older country may become less innovative and creative.

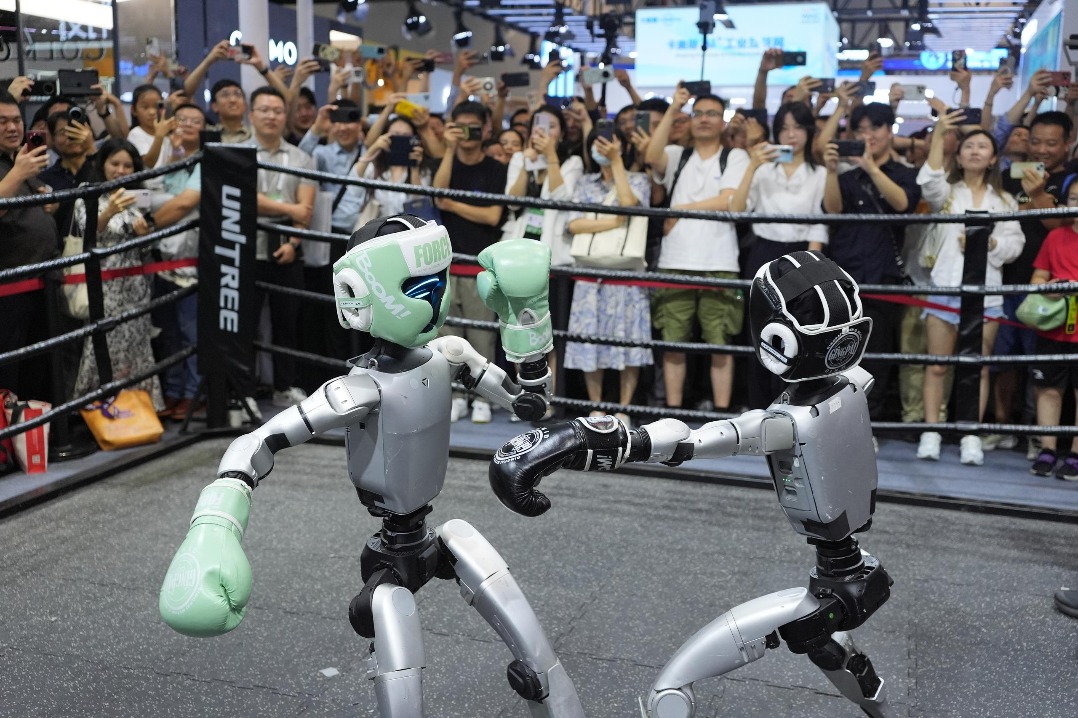

"What Japan did is meaningful to the developed world as the country is probably 10 or 20 years ahead when it comes to depopulation," said Yu in Beijing, adding that introducing immigration, promoting technologies like Artificial Intelligence and robotics and welfare-oriented methods such as redeploying the elderly population in some way while raising the age limit of people working, has already taken effect.

"To be clear, some people have a big problem with prolonged retirement age and I think governments should be flexible on this. I mean, if there are people who have special knowledge, or some kind of skill that is useful, and there are people who want to work way past their retirement age, that's definitely something that the government should be pushing for," Yu added.

Yu said another way to get better prepared for a depopulated future is for the government to get more involved in childbearing and in children's socialization.

"Socialization is the process by which children are raised and educated to become successful members of society. This requires the learning of knowledge, skills, ideas, and values needed for competent functioning in society and more broadly, it requires a culture to be transmitted or reproduced in each new generation," Yu said.

"Under the assumption that we need a more talented and sophisticated new generation to face a more complicated future world, many parents nowadays are no longer capable of teaching their children in that way and there is where the government should get involved, by providing professional guidance while parents should focus more on love and caring for their children."