A hard-luck story that ended well

After a life burdened by misfortune, author finds encouraging words of comfort, Wang Ru reports.

Bad luck always seemed to shadow Yang Benfen. Until that is, when she suddenly, and deservedly, became popular as a writer at 80. This was a turn of events she just could not believe.

The second of six children from a poor family in Hunan province, she was born in 1940, and did menial jobs in childhood. When she finally managed to get a chance to go to school as a teenager, the school closed down just several months before her graduation. If she had been recruited by an automobile transportation company in Tonggu county, Jiangxi province, a few days earlier, she could have become a regular employee, but she ended up doing casual work until retirement.

The change happened more than two decades ago, when Yang resigned. She went to Nanjing, Jiangsu province, where her daughter Zhang Hong lived, to help take care of her young granddaughter.

One day, she read an article written by Zheng Shiping, in which he emotionally recalled his late mother. Yang was deeply moved. Her mother Liang Qiufang had passed away several years before, and she missed her very much. It occurred to Yang to write something about Liang.

"I realized if no one puts my mother's stories down, traces of her will eventually disappear from the world," says Yang.

The calling to write was so strong that she decided to act on it straight away. Between doing household chores, she wrote diligently in the 4-square-meter kitchen.

"When I was waiting for the soup to boil, I sat down and quickly wrote something on a piece of paper with just the booming noise of the smoke exhaust ventilator to keep me company," said Yang in the preface of her first book Qiuyuan, which tells the story of Liang.

Born into a doctor's family in Henan province in 1914, Liang saw her family fortune decline after the death of her two sisters-in-law and father at 12. At 18, she was married to an army officer surnamed Yang, who is Yang Benfen's father, and went to his hometown in rural Hunan province.

Due to turbulence of the times, her father lost his position, was cheated by his relatives, lost properties, and also made a series of wrong decisions. As a result, the family of eight people struggled to live. Since he suffered from bad health, and died in the middle age, the heavy load was put on the shoulder of Liang, who had a pair of "lotus feet", due to the former custom of foot-binding.

The ancient Chinese say the three biggest misfortunes in one's life are losing your father at a young age, a spouse at a middle age, and children at an old age. Liang, unfortunately, experienced all of them. Although she worked hard to support the family by teaching and sewing clothes for others, the family just managed to survive. Ill fortune seemed to follow her and she had to endure the heartbreak of the deaths of her three children, one after another.

Yang Benfen used the name Qiuyuan in the book to refer to Liang, and told her story in the namesake novel. After finishing the first draft, her handwritten manuscripts weighed about four kilograms.

"My mother used to tell her stories to us often, and I was very curious about them. Every time she told me her stories, I formed clear pictures in my mind. When I started writing, I was trying to interpret the pictures into words," says Yang.

"It's very strange that with my age increasing, my memory is getting bad and I often forget what happened a few days ago. But the early memories are still so clear that they seem like being engraved into my heart. I will never forget them," she adds.

Zhang found her mother's writing touching, and pasted it on the online forum Tianya in 2009. To Yang's surprise, many people admired her writing, sympathized with her, and encouraged her. Moved by the goodwill of strangers, she bought a computer, and learned to type so that she could reply the comments.

In 2019, Yang's writing was recommended to Tu Zhigang, editor-in-chief of publisher Pan Press. He was surprised by the "vitality" in the book and decided to publish it.

"The book offers the perspective of an ordinary Chinese woman reflecting on history. Yang has her own style in telling stories, which makes them very vivid," says Xin Ningning, the book editor.

Qiuyuan was published in 2020. In the preface of the book, Yang emotionally wrote "Qiuyuan has come to the world. She once struggled, and experienced both desperation as well as great joy. Today, her 80-year-old daughter tells the story of this ordinary woman to the world".

After its publication, Yang sent three copies to her hometown in Hunan, and entrusted her relatives there to burn them in front of the tombs of her parents and elder brother as an act of commemoration.

Writing, for Yang, is a painful process as she reexamines the lives of her family members, especially the hardships they have gone through. That made her further realize and appreciate how great her mother was.

"As I described in Qiuyuan, after my father's death, my family was very poor. I was a teenager and could have helped my mother a lot to earn money and take care of my younger brothers, but my mother insisted on making me go to school and shouldered all the responsibilities herself," says Yang.

"I didn't realize how incredible this decision was until writing this book. I feel so regretful that I didn't ask her why she was so resolute," she sighs.

But Yang never completed her education, and regrets it to this day. Since the secondary vocational school she was admitted to closed down before her graduation, she then migrated to Yichun, Jiangxi province, to work, where she met her future husband. She got married and the husband promised to fund her return to education, but after the births of her three children, she never had a chance to realize her dream.

As a result, Yang highlighted the importance of education to her children. They were all admitted to universities, which was rare in the 1980s.

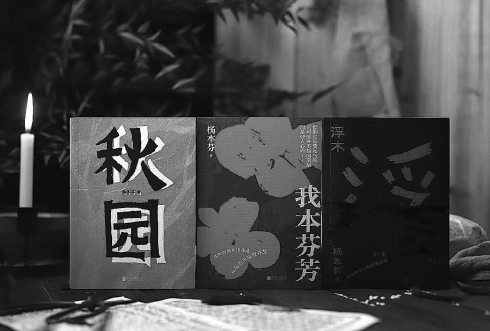

She continues to write. In 2021 her second book Fumu (Floating Wood), about stories of other villagers Yang met in childhood was published and in February the third one, Wobenfenfang (I was fragrant) about Yang's own unhappy marriage, was also published. The three books have achieved 8.9, 8.4 and 8.1 points out of 10 on China's popular review site Douban. Their circulation, in total, has reached 250,000 copies, according to Xin.

"I wrote about my mother, about how our family struggled to live just like a floating piece of wood, and the lives and deaths of villagers who once lived in Central China. If the stories of ordinary people are not put down, they will surely be buried forever," says Yang.

"Many people say the books strike a chord for them, making them think of their own family members. As a matter of fact, we didn't expect them to have such an influence before publishing," says Xin.

Qiuyuan and Wobenfenfang are set to be published in Korean.

"In the first 60 years of her life, my mother was an ideal example of being a good wife and mother who always gave priority to the family," said Zhang to Shenzhen Special Zone Daily. "But since she started writing after 60, she suddenly became a popular writer. We marveled at that."

Yang writes on an iPad now. But due to a failed surgery several years ago, she suffers from frequent knee pain and doesn't often sit in front of a desk. Sometimes she just writes lying on the bed.

"It's my luck to live long enough to see my books come out. But it would be better if I was 10 years younger," she says.

Today's Top News

- China ranks among top 3 trading partners for 157 countries, regions: official

- Restoring truth is the least we can do to serve history

- Israeli airstrikes hit Gaza amid worsening humanitarian crisis

- Book on Confucianism launched in Brussels

- Right track for China-ROK ties lauded

- Nursery rooms help fathers take part in parenting duties with more ease