Guardians of heritage

Restorers battle against the clock to protect cultural treasures from the ravages of time, Wang Kaihao reports.

The statue is a reassuring presence, a calming feature. As if relishing and bathing in the eyesight of Lushena Buddha, an atmosphere of tranquillity and dignity envelops visitors.

For 1,350 years, that 17-meter-high statue has stood in the most hallowed cave among the Longmen Grottoes, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Luoyang, Henan province.

Nonetheless, for Liu Jianshe, the Buddha's charm may not be as impeccable as it is in the enthralled minds of tourists. Over the past half century, his everyday job was to patrol, scrutinize and check his beloved Lushena (the Chinese translation of Sanskrit word vairocana meaning "illuminator") and other Buddhist statues all across Longmen, one of the world's largest grotto temple sites.

The slightest crack did not evade his keen eyes. But even he could not stop the ravages of time. Regrettably, rocks become unstable and the statues are aging, which is inevitable.

"As long as I have strength, I'll carry on the duty," says Liu, 67, from a village only about 5 kilometers from the grottoes, laughing. "Thank goodness, I'm still healthy."

In 1971, Liu followed his father to join a squad of 30-odd restorers to protect the cave in which the Lushena Buddha is located. The cave is named after Fengxian Temple, a site which was in front of the Buddha statue during the Tang Dynasty (618-907) but no longer exists.

Liu recalls that almost every family in his village then had a member who was a stonemason.

"I don't know how many generations of my ancestors dealt daily with stones, and some of them probably carved those grand statues," Liu says, proudly. "We know how to take care of stone best."

In his home village, there was also a Buddha statue with an inscription indicating it was carved in the year 1000. It was considered almost a patron, protecting generations of villagers who had created marvels through chisels and hammers. It is now in the custody of the Longmen Grottoes Research Academy.

Liu's participation in restoring the Lushena Buddha statue in 1971 led him to a career as a conservator at Longmen. Fifty years seem hardly anything in the life span of a grotto, but for a man, it is almost a lifetime.

A new round of massive restoration, consolidating the statue, was launched in December. Perhaps, no one is a better candidate than Liu to join the ongoing project.

There are about 30 restorers working on the scaffolds, but none of those who participated in the 1971 project are involved in this restoration, except for Liu. "I'm the only one standing here again," an emotional Liu says. "It's an honor that I'm still needed."

Much better restoration equipment and technology are used today, but grouting the cracks, precisely and smoothly, still relies on experience and craftsmanship. And, crucially, a human touch.

"Only hands can make details perfect," Liu says.

Birth of Longmen

Back in the mists of time, in 493 to be precise, when the capital of the Northern Wei Dynasty (386-534) was moved from present-day Datong, Shanxi province, to Luoyang, the royal tradition of carving Buddhist grottoes was introduced to this city.

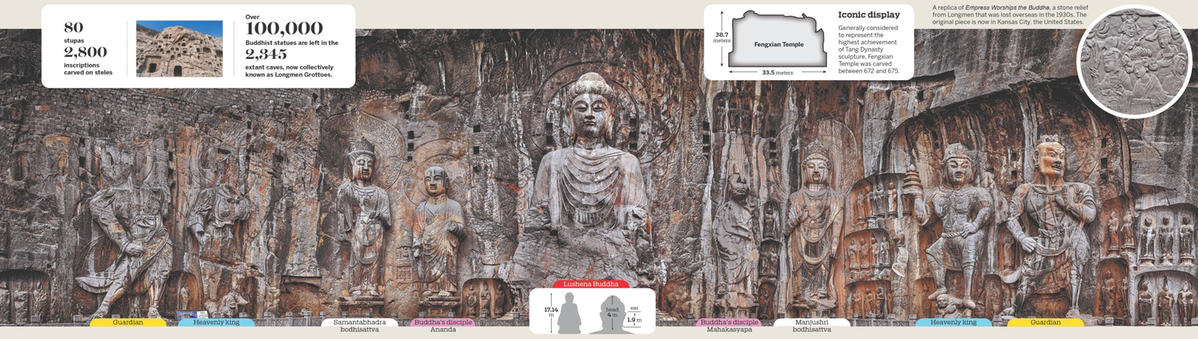

In the following centuries, thousands of caves and niches were carved on the cliff, and the most intensive carving period dated from the end of the 5th century to the mid-8th century. Over 100,000 Buddhist statues were left in the 2,345 extant caves, now known as Longmen Grottoes.

"The sculptures of the Longmen Grottoes are an outstanding manifestation of human artistic creativity," according to UNESCO." (The grottoes) illustrate the perfection of a long-established art form which was to play a highly significant role in the cultural evolution in this region of Asia."

The site of Fengxian Temple, where nine giant statues of Buddhist deities were vividly carved, is undoubtedly the most recognizable icon among the grottoes. Carved during the peak years of the Tang Dynasty, it is speculated that Lushena's facial appearance was based on that of Empress Wu Zetian, and the cave also presented a scene of grand royal rituals from one of the most prosperous periods in ancient China.

As UNESCO highlighted, "the high cultural level and sophisticated society of Tang Dynasty China are encapsulated in the exceptional stone carvings".

The devastating flood in Henan province last summer did not damage this marvelous cave. However, compared with the extreme weather, which can usually be forecast, the invisible but haunting damage of seeping water is a more dangerous enemy to the rocks, according to Ma Chaolong, director of the conservation center with the Longmen Grottoes Research Academy.

Ground penetrating radar, 3D scanning, infrared-thermal imaging and other modern detecting methods, which were unimaginable in the 1971 project, are adopted this time to draft a restoration plan. This will focus on tackling water-related problems and thus strengthen rock solidarity. "It's also like having a comprehensive physical checkup for Lushena," Ma says.

Shi Jiazhen, a veteran archaeologist and director of the Longmen academy, says: "Today, the restoration of grottoes is not merely an engineering project like in the old days. It provides a precious platform for various academic programs involving many other institutes and universities and it will be lastingly beneficial after the renovation ends."

Shi also considers that the case of Fengxian Temple gives new thoughts on how archaeology is viewed.

"People used to think archaeology is to excavate the ground," he explains. "But during restoration of the statues, we also have to research different dimensions of space."

For example, vestiges of gold foil that once covered the Buddha's face were detected, thanks to high-tech equipment, but no historical document that survives ever mentioned this key feature.

Experts know that, no matter how important their work is, it is eventually in the interest of the general public beyond the academic circle.

Tourists are welcomed to offer their ideas on restoration. Some are even allowed to climb up the scaffolds after professional training.

"It's a supervision of our work and a good education program as well," Shi says.

Eternal charm

The renovation is scheduled to last until the end of July. In spite of the conservators' endeavors, Shi knows a bitter but irreversible fact. "Through our work, we can only slow down the aging process of the grottoes, but the rocks will continuously be eroded, and, one day, they will eventually disappear."

Digitization is probably a solution to help people in the future remember their fading glamour. For Longmen, by ushering today's viewers, it can regain its lost luster.

In the 1920s and '30s, like some other Chinese grotto temple sites, Longmen was looted by foreign antique dealers and bandits, which saw its numerous statues being carved up and trafficked overseas. More than 700 spots across the grottoes were found to be deliberately damaged.

Some foreign explorers and Sinologists also took pictures of the Longmen Grottoes, providing an important reference for today's restoration work in the digital age.

"Through analysis of the old photos and field research, we can use virtual rehabilitation and 3D printing to bring damaged relics back to life," says Gao Junping, who is in charge of the information center of the Longmen academy.

Digitization also makes it possible for the separated treasures to be reunited. According to Gao, their recent survey found more than 200 lost Longmen relics in overseas collections.

With the help of overseas institutions, the high-definition digital scanning of separated parts of Buddhist niches are virtually rejoined.

"We can gradually establish a database of the Longmen relics and make them eternally preserved," Gao says.

Currently, the largest-ever project of this type is ongoing. Dihou Lifo Tu (Emperor and Empress Worship the Buddha), a pair of highlighted stone relief paintings from the Northern Wei Dynasty, are now separately housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City. Some of their scattered fragments were left in the Longmen academy.

"Thanks to cooperation among three institutions, the splendor of this national treasure will be shown again in life-size replicas," Gao says.

Last year, a series of short online video clips, in which young dancers of Henan present works featuring the province's cultural relics, including Dihou Lifo Tu, went viral on Chinese social networking platforms.

"You can see how eagerly people want the lost treasures to come back," Shi says. "But if their physical return still faces hurdles, at least we can find a practical solution to let their charm be admired by young generations. Protecting heritage is to face the future."

For Liu, the conservator, the golden age of stonemasons has vanished as if into thin air. Young people want more modern jobs, and the villagers have also moved to a modern residential community.

"My son doesn't deal with stone anymore," he says. "He is a bus driver taking tourists to the grottoes every day. It's all right because my family still serves Longmen."

Longmen means "the dragon gate", a typical auspicious signal in traditional Chinese culture indicating prosperity and success.

Today's Top News

- China's industrial profits down 1.8% in H1

- Thailand responds to Trump's ceasefire call

- Recall vote shows DPP's manipulation runs against Taiwan people's will: mainland spokesperson

- Top DPRK leader visits China-DPRK Friendship Tower

- China proposes global cooperation body on AI

- Scholars propose inclusive human rights framework