Taking a page from tradition

One man's determination turns a new chapter on forgotten art of dragon-scale binding, Yang Feiyue reports.

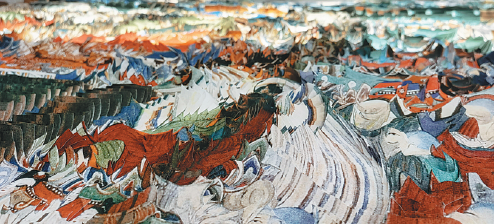

They are book pages but unlike anything modern-day readers are used to. When the pages are unfolded, they resemble the bellows of an accordion or waves approaching a beach. This is the result of dragon-scale binding, a technique that goes back more than 1,000 years to the Tang Dynasty (618-907). Hundreds of sheets of thin paper are delicately and accurately placed on a long strip of paper. They can then roll back into a handscroll or open up to show a moving picture, as the myriad sheets of paper tilt up and seemingly dance when they catch the slightest movement of air. Each page, it was thought, seemed to resemble a scale, hence the description.

Zhang Xiaodong has been intrigued by the intricate tomes for more than a decade and has been trying to save the art form from fading away. He is now the only inheritor of the intangible cultural heritage.

In ancient times, the dragon-scale binding technique was favored by royals and well-off families, because it could shorten a book's length and make for efficient reading and indexing.

However, the complex and time-consuming process required by the distinctive bookbinding style has pushed it to the verge of extinction.

"Every sheet of paper needs to be in exactly the right place," Zhang says.

"Any misstep, as little as a millimeter, could produce an eyesore when the whole thing is displayed."

Currently, the only existing ancient book using dragon-scale binding is preserved in the Palace Museum in Beijing.

"I didn't feel it was a very ancient thing. Quite the contrary, it seemed very modern," Zhang, 41, originally from Zhangjiakou, North China's Hebei province, says, recalling the first time he saw dragon-scale bound books.

The artist had a passion for books in college. Upon entering the Shenyang Aerospace University as an art and design major in 2002, Zhang often went to the library to kill time.

It was then that he stumbled upon works of Kohei Sugiura, a Japanese graphic designer and researcher in Asian iconography.

Sugiura's works gave Zhang new perspectives on the relationship between life and the cosmos.

When Zhang found out Sugiura also engaged in book design, it planted a seed in him to explore the field further.

As Zhang looked into more of Sugiura's designs, he gradually developed his own understanding about book creation.

"I realized making books could be so much fun", and it can allow people to see another world, Zhang says.

"They are not just simply a carrier of words, but their forms, shapes and sizes are also part of the content," he adds.

His experiences in the field while at college led him to pursue a career in book design after graduation.

Since 2008, he has studied under experienced professionals in the field, including book designer Lyu Jingren.

Even though e-books have increasingly made their presence felt, Zhang is confident that people would still appreciate printed books with distinctive physical properties and ornamental attributes, especially those that are collectible.

"E-books do satisfy a particular need, but printed books bring a different enjoyment," Zhang says.

In his mind, books are the buildings that house words and poetic meanings. And just like the buildings in our everyday lives, their architecture needs to be both functional and aesthetic.

"It's relatively easy to get information on other binding techniques, but that's not the case with dragon-scale binding," he says.

When Zhang began his project, it was not plain sailing.

After searching to get materials that were traditionally used in bookbinding, such as rice paper, bamboo, silk and wood, Zhang was faced with the most crucial and difficult part of the binding process: controlling the placement of each page.

With few historical references to fall back on, Zhang could only continuously check with book design experts, and refer to the Palace Museum's one existing dragon-scale bound book to get it right.

The rest involved perseverance-trying over and over again until it was correct.

"The whole process was one of desperation," Zhang recalls.

His first attempt was to bind the ancient Buddhist text, Diamond Sutra, in dragon-scale style.

When he finished the first small section, he wasted no time in sharing his brilliant work with his teacher Lyu, who rapidly poured cold water on the flames of his enthusiasm.

"He told me I got it all backward," Zhang says. "So, it was back to the drawing board and I had to start from square one again."

Zhang's determination and interest in the ancient binding technique got him through those early setbacks and, eventually, after two and a half years, he tasted success with the completion of a 73-meter-long scroll with 217 scales.

Instead of completely copying the old style, he innovated. Zhang arranged the patterns on the top edge of each paper sheet, and once they were all rolled out, they formed an image of Buddha.

"Images can offer stronger stimuli (to the eye) than words, and people usually first get interested in the image they see before starting to turn the pages," he explains.

"The image breaks as the pages are turned, symbolizing a progressive reading experience."

The goal is to create a three-dimensional dialogue between a reader's senses and the book.

"You can smell the paper, touch and feel it, all of which can be part of your reading experience," he says.

It's the idea of integrating the shape of a book into its content that drove Zhang to design, in dragon-scale binding, Dream of the Red Chamber, a classic novel by Cao Xueqin during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911).

The book runs to more than 100 meters in length and sits more than a meter high when closed. It has 120 chapters with re-creations of 230 images by the Qing Dynasty painter Sun Wen.

As his experience grows, Zhang further explores the possibility of this unique expression, and has developed his own Infinite Leaves series. The superposition of pages builds a multidimensional world, attaching a new spatial meaning to the traditional bookbinding technique.

His new works take the form of unique "paper sculptures", and shift to a more abstract visual language. These works appear more mysterious under light, thanks to the casting of shadows, as when viewed from multiple angles, there appear Buddha statues and subtle landscapes.

Through years of bookmaking, Zhang has become a paper expert. In addition to traditional rice paper, he has also experimented with various materials such as silver paper and chestnut shell dyed paper, offering the viewer different visual and tactile experiences.

For example, Zhang obtained sand-colored paper by soaking and fermenting chestnut shells for more than two years.

Zhang's solo exhibition is being staged in Shanghai and will run until April 17.

"This bookbinding technique requires a very high degree of precision, and any slight deviation will affect the final overall effect," says Zhang Linmiao, curator of the exhibition.

"The paper grows, extends, folds, rises and falls, fully revealing the artist's sophisticated skill and unique perspective," Zhang Linmiao adds.

Speaking about his future plans, Zhang Xiaodong says he would keep an open mind to enrich his artistic creations.

"I believe printed books will keep evolving in their formats and won't disappear, so it needs constant learning and willingness to try new things to come up with more creative works," he says. "What I need to think about is how I can do my part to push them in a certain direction."

Today's Top News

- Xi taps China's deep wisdom for global good

- New rules aim for platforms' healthy growth

- Chinese web literature grows overseas

- Postgrad exam trend points to thoughtful approach

- World's highest urban wetland a global model

- How China's initiatives are paving a new path to a better world