Tragic legacy still matters

With a spike in hate crimes against Asians in the US, Paula Yoo's new book discusses how one fatal incident in 1980s Detroit sparked a nationwide movement, May Zhou reports in Houston, Texas.

In 1982, Japanese auto companies were on the rise and many American autoworkers, incited by politicians' rhetoric, blamed Japan for losing their jobs. Anti-Japanese sentiment was simmering.

A bar fight in the auto city of Detroit turned fatal, leaving Chinese American Vincent Chin, who was enjoying his bachelor's party a few days before his wedding, beaten to death by two white men, autoworker Ronald Ebens and his stepson, Michael Nitz.

As Chin's friend Jimmy Choi held him in his arms, his last words were, "It's not fair."

A waitress later testified in court that Ebens was shouting: "It's because of you … that we're out of work."

Fast-forward to 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic broke out, many Americans blamed the origin of the virus on China. Again, incited by politicians' rhetoric, crimes against Asian Americans have climbed sharply in the last two years.

"It's not just racism, it's xenophobia. The problem in this country is that people cannot separate our country of origin and cultural heritage from our American citizenship," says Paula Yoo, an accomplished writer and musician.

Yoo, whose credits include screenplays for popular TV series The West Wing and Supergirl, shared her thoughts on racism by discussing her book-From a Whisper to a Rallying Cry: The Killing of Vincent Chin and the Trial that Galvanized the Asian American Movement-published in 2021, at the two-day conference Moving Forward: Challenging the Racism, held at the Holocaust Museum Houston from Feb 26-27.

The conference complemented the ongoing museum exhibition Speaking Up: Confronting Hate Speech, says Nancy Li, event co-chair and museum board secretary.

"It takes a look at the history of Asian Americans and how to move forward through civic engagement, legislation, legal action and such, to foster equality and justice for all," says Li.

Yoo's new book, which has won numerous awards, examines the killing, the trial and the verdicts that followed Chin's death. Ebens and Nitz pleaded guilty to manslaughter, received only a $3,000 fine and three years' probation.

"Let the punishment fit the criminal, not the crime," presiding Judge Charles Kaufman said at the time.

Such a lenient sentence sparked outrage and led to the first federal civil-rights trial involving a crime against an Asian American. It lost due to a technicality, but it galvanized what came to be known as the Asian American movement, says Yoo.

The movement began in Detroit but spread nationwide. The Chinese American community joined hands with the Japanese American community and other Asian communities and the term "Asian American" became mainstream, says Yoo. The movement was also joined by the all-inclusive American Citizens for Justice.

As time passed, recollection of the name Vincent Chin faded. However, his name and story resurfaced after anti-Asian hate crimes spiked during the COVID-19 pandemic, says Yoo.

"I myself have experienced anti-Asian racism because of the pandemic. When I was walking down the street one day, a car drove by and someone yelled 'Chink!' at me. A white man refused to get on an elevator with me even though we were both wearing masks," she says.

In Atlanta in March 2021, a white man shot and killed eight people, six of them of Asian descent. "But yet the sheriff quoted the killer as saying he was having a 'bad day' and they did not, at the time, consider it a racist hate crime," Yoo points out.

That "bad day" comment, just like the lenient sentence in Vincent Chin's case, told the victims' families and the Asian community that "you don't count when it comes to civil rights. You don't count when it comes to the dialogue on racism in this country," Yoo says. "This is why Vincent Chin's legacy matters."

Today, the term Asian American has expanded to a more inclusive term AAPI-an abbreviation that stands for Asian American and Pacific Islander.

Yoo says that the fact that AAPI history wasn't taught in primary school was the key reason why AAPIs are often viewed as outsiders in this country.

She recalls that, a few years ago when she visited her parents' house, she found a box filled with drawings she had done in elementary school.

"I smiled at the cute images of myself in kindergarten, with my black hair and dark eyes. I clearly identified as Korean American. But as I flipped through the pages, I noticed something was off.

"The drawings of me with black hair and dark eyes were soon replaced with blonde hair and blue eyes. I was holding a tangible piece of evidence as to why representation matters not just in books, but in our schools and libraries," she says.

A recent survey reported that one out of four Asian American youths reported experiencing physical and verbal anti-Asian harassment and bullying because of the pandemic. That number could be reduced to zero if AAPI history was taught in school, Yoo says.

The media also needs to do a better job to cover news involving AAPI, says Yoo, who has worked as a journalist for the Detroit News and the Seattle Times.

"What we have seen in the social media constantly are videos of a black or brown man beating up an elderly Asian person. However, a recent survey found that 70 percent of all anti-Asian crimes were done by white perpetrators," Yoo says.

Such skewed coverage makes the minority communities look more racist than white people, explains Yoo. "That kind of treatment ignores the real elephant in the room, which is the white supremacism and systemic racism," she says.

Today's Top News

- China sees over 33.7 billion inter-regional trips in H1

- BRICS justifiably calls for IMF reforms

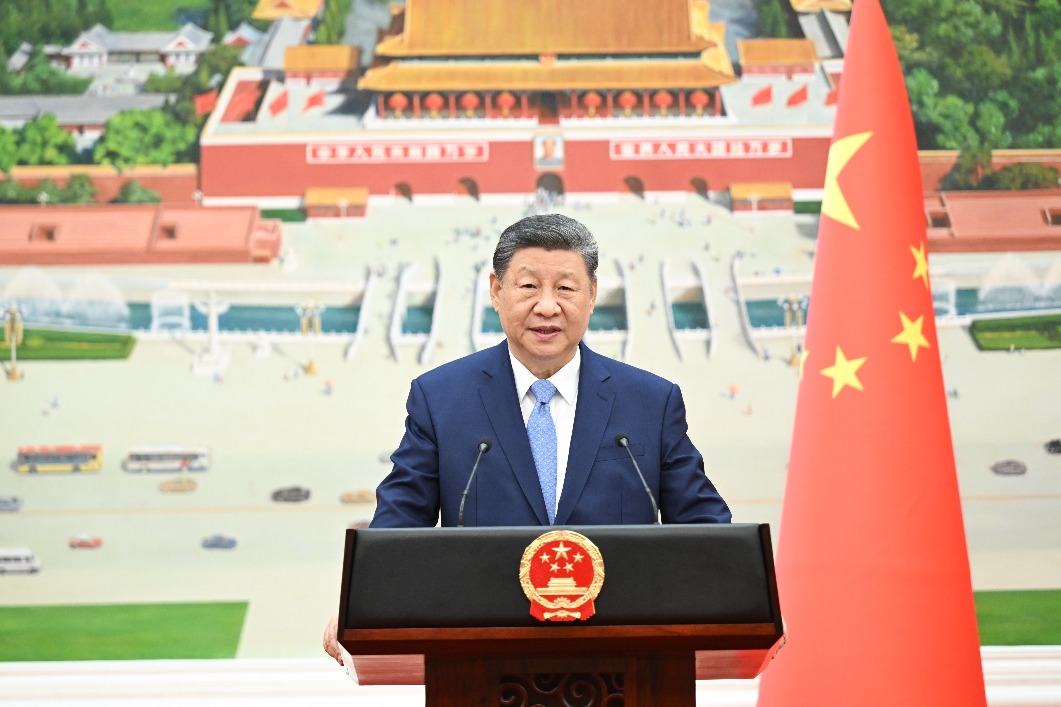

- Xi receives credentials of new ambassadors to China

- Sino-US trade talks key to global supply chain

- Medical insurance covers 95% citizens

- Great opportunities mark 50th anniversary