US inmates exploited in private prisons

Forced labor, operators' drive for profits among issues found in jail facilities

The private prison system in the United States is rife with issues such as forced prisoner labor and operators' drive for high profits, research has shown.

The US incarcerates more people than any other country. Despite having less than 5 percent of the world's population, the country locks up 20 percent of the world's prisoners, according to Prison Policy Initiative, a nonprofit group that researches the harm caused by mass incarceration.

In 2019, 2.1 million people were incarcerated in the US criminal justice system, data from the US Department of Justice shows. This means that 1 in 40 US adults was put under some form of supervision.

Private prisons have a long history in the US, but first attracted attention in the 1980s as a result of then-president Ronald Reagan's war on drugs. That campaign filled the country's jails.

To alleviate overcrowding, the Federal Bureau of Prisons began to contract with operators of private prisons, a policy that gave rise to companies like the Corrections Corporation of America, since rebranded as CoreCivic.

According to The Sentencing Project, an advocacy center working to reduce incarceration in the US, the country has the world's largest private prison population. Around 8.5 percent of the 1.5 million people locked up were held in private facilities, the organization said.

The center estimated that another 26,249 people of those detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE, were held in privately run facilities in 2017. They accounted for 73 percent of those detained by the agency.

Two of the largest companies in the industry are CoreCivic and GEO Group, which together have more than half the market share in the private prison business. They generated a combined revenue of $3.5 billion in 2015.

Private prison operators, as a for-profit business, have to contend with a range of pressures. For one, they "face a challenge in reducing costs and offering services necessary to maintaining safety in prisons while also generating a profit for shareholders", researchers at The Sentencing Project found.

One way they tried to save money is by employing workers on low wages to run the facilities. The website CorrectionalOfficerEDU estimates that correctional officers working at private prisons earn an average annual salary of $30,460, at least $20,000 less than their peers at federal prisons.

A 2016 report by the Department of Justice's Office of the Inspector General reviewed conditions at for-profit prisons by examining areas such as the presence of contraband, reports of incidents and inmate discipline.

"We found that in a majority of the categories we examined, contract prisons incurred more safety and security incidents per capita than comparable BOP (The Federal Bureau of Prisoners) institutions," the report said.

People held at privately operated facilities are also twice as likely to report that they were sexually victimized by staff as people in public facilities, according to a 2014 special report by the US Department of Justice.

An issue attracting increasing concern is forced labor.

The Convention Concerning Forced or Compulsory Labor, adopted by the International Labor Organization in 1930, defines forced labor as "all work or service which is exacted from any person under the menace of any penalty and for which the said person has not offered himself voluntarily". The private prison system in the US has long faced allegations of forced labor.

In 2019, immigrants at detention facilities owned by the GEO Group sued the company for allegedly violating the California Minimum Wage Law by paying them $1 a day for their labor.

Solitary confinement

Under GEO's Housing Unit Sanitation Policies, the company also requires all detained immigrants to work for free or face penalties, such as interference with their immigration cases, solitary confinement, or punitive housing reassignments.

In 2017, Washington state's attorney general sued GEO Group for allegations that the company violated the state's minimum wage laws by mandating immigrant detainees work for $1 a day.

Wilhen Barrientos, an immigrant from Guatemala, who was forced to labor for CoreCivic, earned an average of $1 to $4 a day as part of the "Voluntary Work Program", an ICE program that requires private immigration detention contractors to pay detainees at least $1 a day for work.

"When I arrived at Stewart, I was faced with the impossible choice-either work for a few cents an hour or live without basic things like soap, shampoo, deodorant and food," Barrientos, a plaintiff in a lawsuit against CoreCivic's Stewart Detention Center in Lumpkin, Georgia, said in a media statement.

The conditions at one private prison were recorded by journalist Shane Bauer, who went undercover as a correctional officer at Winn Correctional Center in Louisiana, which was run by CoreCivic. He wrote his experience in the book American Prison.

Bauer recounted that compared with public prisons, private correctional facilities pay guards less, a practice that leads to low staffing. As a result, the companies usually don't have the prisoner's best interests at heart. "I saw-I met a man who had lost his legs and fingers to gangrene in the prison who had been begging for months to go to a hospital and would just repeatedly be given MOTRIN (a type of pain and fever relief) and put back, you know, on his tier," Bauer said in an interview with NPR in 2018 about his time in the prison.

Today's Top News

- Washington should realize its interference in Taiwan question is a recipe it won't want to eat: China Daily editorial

- Responsible role in mediating regional conflict: China Daily editorial

- US arms sale only a 'bomb' to Taiwan

- China-Cambodia-Thailand foreign ministers' meeting reaches three-point consensus

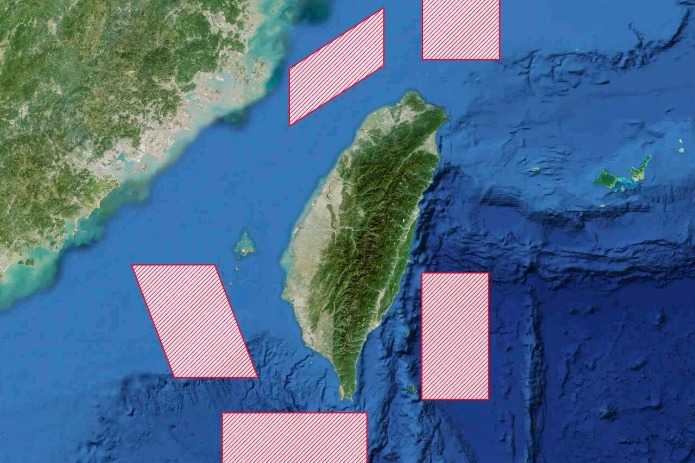

- Drills demonstrate China's resolve to defend sovereignty against external interference

- Trump says 'a lot closer' to Ukraine peace deal