Restoring the faith

Tiantishan Grottoes get the attention needed to keep cultural relics in good shape, Wang Kaihao in Beijing and Ma Jingna in Lanzhou report.

Editor's note: In 2020, the State Council, China's Cabinet, issued the first national-level and long-term guideline specifically for the protection and study of grotto temples in China. China Daily journalists talk with researchers and conservators to showcase the cultural splendor and how people take care of them.

A 28-meter-high Buddha statue stands on a cliff in Wuwei, Gansu province, along with his heavenly guards. In spite of the solemn atmosphere, the Buddha's face wears an enigmatic smile, from which many pilgrims derive a sense of inner peace.

As the biggest statue in Tiantishan Grottoes, the Buddha, in No 13 Cave of this Buddhist grotto complex, has been there for over 1,300 years.

In ancient times, it was probably hard to reach this sacred place due to the rugged landscape.

The name, Tiantishan, means "a mountain with a ladder to heaven".But today's visitors have an easier way to reach the spot.

A dam was erected just in front of the Buddha statue in 1960. People can enjoy the view of the reservoir and the cultural heritage from the top of the dam. The landscape explains how modern people live with history.

Nevertheless, continuous seeping water from the grotto rocks has been a threat to the Buddha statue for a long time.

The feet and bottom of the garments on the Buddha and his heavenly guards have eroded. Appearance of the Bixi (a turtle-shaped sacrificial animal) statues, upon which the guards stand, has also been affected. Some rocks began to collapse. Mice often made their shelter in the cracks of the statues.

"Water and salt kept oozing out of the rock," says Liu Zhi, director of Tiantishan Grottoes Protection and Research Institute.

"The aged statue had 'disease'. It urgently needed to be cured."

Restoration program

A project to rescue the cluster of statues was launched in May 2020 and was completed in August. The program was led by Dunhuang Academy, an institution based in Dunhuang, Gansu, best known for its expertise in protecting the Mogao Caves, a complex of Buddhist grottoes and a UNESCO World Heritage Site thought to have been built between the fourth and the 14th centuries.

Unstable rocks were cleaned in Tiantishan's No 13 Cave. Frames made of waterproof material, such as fiber-reinforced plastics, were set inside the foundation of the statues. Pebbles were used to fill the frames and keep the ground water from rising.

A drainage system was also designed to usher the water in the statue's foundations into a well.

"It's impossible to thoroughly keep water off the statue," says Qiao Hai, the restoration program leader. "The key is to drain it smoothly."

Nevertheless, traditional material like mixed earth and foliage dominated the restoration. It was how the Buddha statue was built in the beginning.

Referring to old pictures and surviving Buddha statues elsewhere from the same historical periods, Qiao's team fixed the Bixi and Buddha's feet as well.

Though the feet were broken earlier, the renovation team decided to restore them.

"For integrity of the statue, we still preferred a beautiful and harmonious appearance," Qiao says.

"It took rounds of trials and expert appraisals before we chose the best method."

After the No 13 Cave of Tiantishan Grottoes was constructed during the Tang Dynasty (618-907), it had been renovated several times throughout the following millennia. And, completion of this most recent restoration does not mean the work is done once and for all.

"I cannot promise how many years the Buddha will be secure due to our restoration," Qiao says.

"But a scientific and dynamic monitoring system will closely follow how the statues' natural environment changes.

"Once we detect a problem, we'll fix it via restoration on a smaller scale. It's a long-term project, and prevention will play a key role."

Statues at museum

Eighteen caves remain in Tiantishan today. In 2001, the grottoes got inscribed onto the list of national-level cultural heritage units under key protection.

Though the site's popularity among tourists cannot compete with Mogao Caves, the significance of Tiantishan has always been highlighted by scholars.

The oldest grottoes in Tiantishan were carved in the fifth century, hosted by a regional king, and its construction lasted until the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911).

"Consequently, it has a key status in the history of Chinese grotto temples and remains an important witness of how Buddhism spread in China," says Liu, the Tiantishan institute's director.

According to studies by the late Su Bai, a renowned archaeologist at Peking University who focused on Chinese grotto temples, Tiantishan represents a typical style of early-stage Buddhist statues in China that had great influence on grottoes of later periods.

For example, Longmen Grottoes in Henan province and Yungang Grottoes in Shanxi province, both UNESCO World Heritage sites, were deeply influenced by Tiantishan. Even Mogao Caves largely absorbed elements of Tiantishan.

"Tiantishan is seen by historians as an origin of Chinese grotto temples," Liu says. "But systematic studies of it are still quite new, compared with the more well-known sites."

Tiantishan first came to the attention of the wider public due to the construction of the reservoir to facilitate irrigation in the arid region.

According to the calculations of its designers from the former Soviet Union, the grottoes would be inundated once the construction of the reservoir was finished. Consequently, all frescoes and Buddhist statues in the grottoes were relocated to Gansu Provincial Museum in Lanzhou, capital of the province, in 1959.

Due to the huge size of the statue cluster in No 13 Cave, they became the only ones to remain in situ.

People later found that, over the following decades, the highest level of water in the reservoir was still 5 meters below the lowest grotto of Tiantishan.

In 2006, the relocated relics from Tiantishan were transferred back to Wuwei.

A comprehensive conservation program covering the returned relics started in 2015, led by Dunhuang Academy. The project was completed in June, giving new life to over 70 statues and frescoes, which cover over 300 square meters. For the stability of the relics, Liu says it is not suitable to put them back in the caves.

"Unlike statues in many other grotto temples, these statues have become 'movable' relics, and are better placed in museums," he adds.

A new museum for the display of the returned relics has been planned on the site of Tiantishan. Before their new home is set up, some are now being temporarily exhibited at Wuwei Museum.

About 170 old photos of the 1959 relocation have been collected from scholars and Wuwei residents, which Liu says are important references for future display of the relics.

The lack of research capacity is another bottleneck. Liu's institute is composed of 23 people, but only five are full-time researchers.

Though academic exchanges with other institutions like Dunhuang Academy will continue to play an important role in the study of the site's treasures, Liu says efforts will be made to introduce more researchers to Tiantishan.

To echo the first national-level guidelines, specifically for the protection and study of Chinese grotto temples, which was issued by the State Council in October 2020, a comprehensive study of Tiantishan Grottoes was carried out from November to April and the first official "status quo" report of the grottoes was produced.

"We want to have the best conditions to welcome the relics home," Liu says.

"The newly completed restoration is just a beginning. Many more projects will follow."

Today's Top News

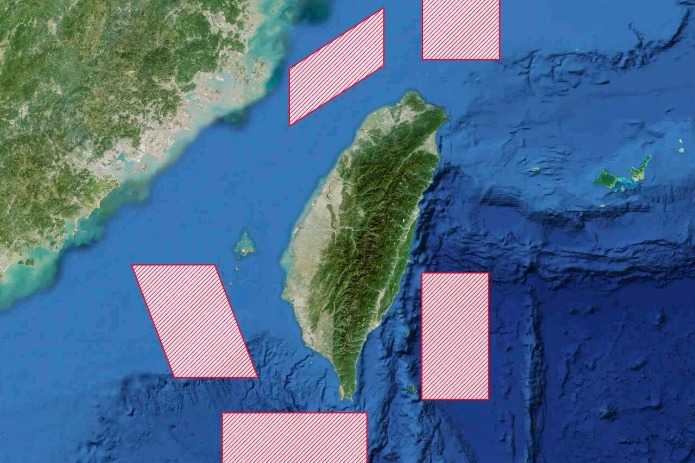

- Drills demonstrate China's resolve to defend sovereignty against external interference

- Trump says 'a lot closer' to Ukraine peace deal following talks with Zelensky

- China pilots L3 vehicles on roads

- PLA conducts 'Justice Mission 2025' drills around Taiwan

- Partnership becomes pressure for Europe

- China bids to cement Cambodian-Thai truce