On the 'write' side of history

Exhibition celebrates UNESCO's recognition of key archaeological site and inscriptions that confirm depth of Chinese civilization, Cheng Yuezhu reports.

In China, there has always been a fine line between language and calligraphy. From the oracle bone inscriptions to the scripts that are widely adopted today, the transformation of Chinese characters and that of calligraphy seem to closely interact with one another.

Fascinated by such dynamics, artist Lu Junzhou is driven to explore their extremes by using his avant-garde calligraphy style to present the prehistoric pictographs-created even before written Chinese-with his Liangzhu Writing exhibition at the Liangzhu Culture and Arts Center in East China's Zhejiang province.

Open from July 6 to Sunday, the exhibition celebrated the two-year anniversary of the Archaeological Ruins of Liangzhu City being granted UNESCO World Heritage Site status.

At the ruins, which provide evidence of Chinese civilization's 5,000-year history, a seminal discovery was that many artifacts, such as receptacles and tools made of ceramic and stone, were found inscribed with pictographs.

Although their meanings are yet to be deciphered, many experts believe that these inscriptions, if not the precursor of Chinese characters, were at least symbols with communicative functions used by ancient Liangzhu residents to convey certain messages.

When Lu was invited on a field trip to the archaeological ruins and Liangzhu Museum, he was awed by the aesthetics of the sites and the pictographs, both of which revealed to him a kind of crude beauty.

"Our language and words are being constantly enriched, but it seems to me that it's getting harder and harder to express ourselves without misapprehension," Lu says.

"In ancient times, the way people communicated was almost animal-like. They could complete their communication with a few simple sounds. These simplistic expressions fascinate me greatly."

With a keenness that each one of his exhibitions should display new work with connections to the local culture, after returning from the field trip, he concentrated on creating a series of pieces centered on the pictographs.

An iconic piece in the exhibition is an art installation entitled Qianzishi (stones with a thousand characters), which features several hundred stones placed in circular, concentric layers, giving the work a radiating effect.

The inspiration for the exhibition comes from the Liangzhu city walls, the foundation of which are made of stacked stones. Seeing the walls during his field trip, Lu was immediately reminded of the architectural methods in his childhood village near Wenzhou, also in Zhejiang province, whereby locals built walls with stones found in the rivers and streams.

So, he and his brother went to collect stones from the river in his hometown and transported them to the museum.

Shi Xingeng (1911-39), the discoverer of the Liangzhu site, wrote a preface in his book reporting on the preliminary excavation of the ruins in the 1930s, which Lu replicated on the hundreds of stones.

"The preface moved me greatly. When he wrote and published the book, he had already joined the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression (1931-45) and Liangzhu was occupied by the Japanese army," Lu says.

"As a young intellectual who held such love for his hometown and his country, the preface was so much more than an archaeological report. It is his reflection on the culture of a nation."

After writing down the text, Lu then collaborated with the curation team in arranging the stones to present a conversation across time and a tribute to Shi.

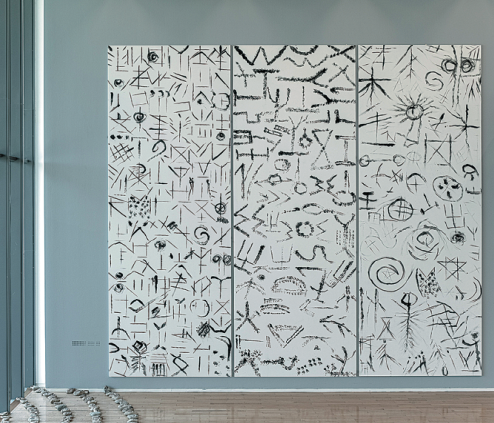

Also in the exhibition, Lu showcases his own rendition of the pictographs found on the artifacts, including a large-scale calligraphy work. Although the symbols have little in common with modern Chinese characters, Lu does not find it difficult to create calligraphy works based on them.

Curator of the exhibition, Zhang Weina, commends Lu as a genius, with a unique calligraphy style to be able to reproduce the primitive imagery. "The pictographs in Liangzhu Culture are very natural and interesting, and his writing allows us a deeper understanding of Chinese civilization more than 5,000 years ago," Zhang says.

With a belief that Chinese characters have great potential in terms of their shape and structure, Lu's style of calligraphy is an unconventional one that is not always accepted by the general public.

While the conventional standard for a good calligraphy is to imitate the style of a particular master, such as Wang Xizhi of the Eastern Jin Dynasty (317-420) or Mi Fu of the Song Dynasty (960-1279), Lu wants to present his own way of expression, unrestrained by any standardized font.

Lu says that growing up in the 1980s, he was actively involved in the calligraphy scene. With a fervor for calligraphy, he participated in any competition he heard about and won wide acclaim.

In his early teenage years, he played to the crowd by fitting into the orthodox calligraphy criteria and imitating the styles of ancient calligraphy masters, only experimenting with new forms of calligraphy in private.

"I am not a person who likes to go by the book," Lu says. "By the time I entered high school, I stopped participating in any competition or organization. But I continued to practice calligraphy and explore unconventional methods in the art form, until my first solo exhibition in 2018 at Suzhou Museum.

"Although texts are very important to my creations, in the end I aim for 'de-textualization'. I hope that when visitors come to see my works, instead of reading the prose or poetry created by the classical masters, they can see my artistic language and my expression."

In Lu's vision, the ideographic origin of Chinese characters gives Chinese calligraphy the potential to be portrayed in different forms, such as installation art, and to be appreciated despite language barriers.

"Cultures are diversified and, sometimes, even alienated from one another, but the languages of art, music and dance, for example, are shared by all humanity," Lu says.

"So I've been thinking, if we emphasize the artistic elements of calligraphy, it will become a language understood by all. Even for an international audience that doesn't understand Chinese, people will be able to grasp the rhythmic pattern of the writer and interpret Chinese calligraphy as a visual art."

Today's Top News

- Jimmy Lai found guilty of colluding with foreign forces

- Hong Kong court opens session to deliver verdict on Jimmy Lai's case

- China's economy posts steady growth in Nov

- Death toll rises to 16 in Sydney's Bondi Beach shooting

- Firm stance on opening-up wins praise

- World looks to new engines for growth in 2026