US university, college towns face dual threat

Combination of pandemic and remote learning results in hardship

Many of the cities and towns that are home to the 4,000 universities and colleges in the United States are worried-and some of them are going broke.

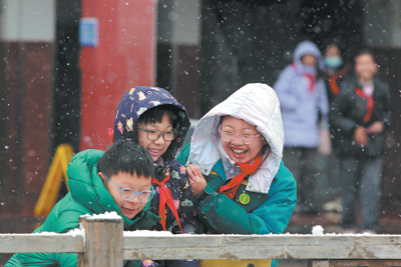

College towns, like many other areas of the country, experienced major losses of income and jobs in the spring as a result of the coronavirus pandemic.

The outbreak also led to thousands of students leaving campuses for home.

Now, as campus reopening plans are announced for the fall semester, the use of remote learning to prevent the spread of COVID-19 will keep thousands of students at home.

Numerous international students, a major source of revenue for many US universities and colleges, will be among those who remain at home, not only because of the threat from the disease-they also face US travel restrictions and new immigration policies.

A report last month from the Institute for International Education found that 50 percent of US colleges had experienced a reduction in applications from international students.

Meanwhile, a report from the National Foundation for American Policy warned that international enrollments could fall by 63 percent to 98 percent from the levels in 2018-19 as students stay away from US schools.

According to the Chronicle of Higher Education, only some 23 percent of US universities and colleges still plan to fully or mainly conduct in-person classes this fall, while 15 percent will offer a mix of online and in-person instruction. For the rest, full or primarily virtual instruction will be used during the semester.

Cases of COVID-19 have been reported at schools that have reopened. At the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, outbreaks led to plans for in-person instruction being abandoned.

Stephen Gavazzi, professor of human sciences at Ohio State University, told NBC News: "When a university sneezes, the town gets pneumonia. Now, when the university has pneumonia, what does that mean for the town?"

In Athens, Ohio, where the university is located, the lack of students and parents attending graduation ceremonies, homecomings and sports events in the spring led to hotels losing millions of dollars, including occupancy taxes that fund part of the city's general budget. Several local businesses closed.

The university is the city's largest customer for water and sanitation services. Thousands of its 17,000 students left in May, resulting in a budget shortfall of $100,000. Mayor Steve Patterson expects a similar shortfall next month.

"It's bordering on the worst-case scenario," Patterson told CBS Money-Watch, a personal finance website. "If the university were to move to a largely online model, I'm going to start to see more businesses permanently closed just because they can't make ends meet."

Canceled commencement ceremonies have cost South Bend, Indiana, home of the University of Notre Dame, about $17 million in lost revenue.

Kurt Janowsky, the owner of Navarre Hospitality Group, said: "It's our busiest weekend of the year. Commencement is a four-day extravaganza. Our restaurants and catering businesses are incredibly busy, so losing it is a body blow to South Bend."

In Amherst, Massachusetts, home to the University of Massachusetts and Amherst and Hampshire colleges, canceled commencement ceremonies cost the town about $3 million in revenue, according to the local chamber of commerce.

Last month, the town council raised annual water and sanitation charges by an average of $100 per household due to a significant reduction in the use of water after about 25,000 students left-nearly 75 percent of the local population.

In Ithaca, New York, home to Cornell University and Ithaca College, 25,000 students, who contributed $4 million per week to the city's economy, have left. Mayor Svante Myrick said he is prepared to cut $14 million from the $70 million budget. He has already furloughed 25 percent of employees.

Ronald Filippelli, the mayor of State College, Pennsylvania, home to Pennsylvania State University's main campus, said, "The absence of students since March has been crippling our city." He estimated the losses to be in seven figures.

"We are a city of 42,000, and two-thirds of our residents are students," he said at a briefing for congressional staff members hosted by the National League of Cities, or NLC, on July 20.The gathering was called to discuss how the pandemic has affected the economies of university and college towns.

State College municipality shut down parking, resulting in revenue losses of about $750,000, and has also delayed a number of improvements, while Penn State has furloughed many workers and laid off dozens.

More than 8,000 international students are enrolled at Penn State and the absence of a large number of them will further affect State College and the school.

Penn State is resuming classes and going ahead with plans to offer in-person teaching, along with a range of hybrid and online learning options. However, there will be no football weekends this year, with the Big Ten Conference, one of the oldest college athletic bodies in the US, announcing this month that the season had been canceled.

Penn State football games usually attract more than 100,000 fans, with many coming from outside the area. They bring revenue to bars, hotels, restaurants and many other businesses.

Local leaders said during the NLC meeting that with many classes being held online and the attractions of campus life off-limits, it is harder to interest students in returning.

Ames, Iowa, home to Iowa State University, has reported a $9.1 million budget shortfall for the 2019-20 fiscal year.

Gloria Betcher, an Ames City Council member, said local hotels have lost $8.9 million in revenue since March, and two have closed. Students account for about 50 percent of the population of 67,000.

In Ann Arbor, Michigan, students at the University of Michigan contribute an estimated $95 million a year to the local economy, excluding spending on housing and groceries.

According to Destination Ann Arbor, the city's convention and visitors' bureau, travelers spend as much as $12 million collectively at a single football game. Of the nearly 3 million visitors in 2018, about 60 percent had some kind of relationship with the university, and nearly 30 percent came to the city for the school's athletic events.

Many small towns across the US are in the same predicament.

In Hickory, North Carolina-home to Lenoir-Rhyne University and Catawba Valley Community College-local sales tax revenue has fallen by $100,000 a month and 28 employees have been furloughed.

Schools are absorbing the financial impact of students leaving in the spring.

Last year, cities with higher education institutions were forecast to see an 11 percent rise in employment, according to a report by McKinsey &Co. Instead, schools hit by COVID-19 are cutting jobs.

The Chronicle of Higher Education reported that according to the US Labor Department in May, the number of people employed in higher education in the country fell by 19,200 in February and March.

Some schools are freezing salaries, but are hiring. Ohio University has announced layoffs, while at the University of Wisconsin, most of the 3,500 employees will be furloughed for six to eight days during the next five months.

The University of Tennessee in Knoxville has paid $15 million in refunds to students, while Clemson University in South Carolina has told its board of trustees it could lose up to $100 million if classes are held online in the fall. However, it will still hold in-class instruction.

The University of Michigan is predicting pandemic-related losses of as much as $1 billion across its three campuses by the end of this year. The school's medical workers have been furloughed and construction of a new hospital halted.

Ari Weinzweig, co-founder of Zingerman's, a delicatessen company with a number of outlets in Ann Arbor, said he has furloughed nearly 450 of 700 employees, and estimates that sales have fallen by 50 percent of the level since the onset of the pandemic.

"It's only going to get worse because nobody, not even really the school, knows how many students will come back," Weinzweig told the The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization.

Another cause for concern is the national census, which every decade determines the number of seats each state has in the House of Representatives and the amount of federal funding distributed to local and state governments.

College towns reported significant undercounting, as students were leaving campuses when the census was being carried out.

Students at Ohio University comprise 75 percent of the local population, so excluding them from the census could result in the official headcount being slashed from 24,000 to 6,000.

In Ithaca, a remote college town, 50 percent of the population consists of students-meaning that if they are not counted, the figure could shrink from 31,000 to 15,500.

Today's Top News

- China's message in Davos draws praise

- Consensus, not coercion, key to Ukraine crisis

- Wide view seen as key to full grasp of China

- Trump seeks immediate talks on buying Greenland

- Cutting edge of manufacturing boosts resilience

- Asian Cup run reignites soccer hope