US doctor comforts patients in last days

Editor's note: When the planet's most populous country thrives, the rest of world does too, and friends from other lands have been willing to help. This series explores the contributions of foreigners to China's success.

Like an angel descending from the heavens, Eric Miller, a 52-year-old American doctor with light skin and blue eyes, makes his appearance in a remote village in Shanxi province, known for hardworking coal miners and the Loess Plateau.

Miller's arrival is always a blessing, the beginning of a season of serenity.

He came to the village to comfort the dying, to relieve their suffering in their last days and help them exit the world with dignity.

Palliative care-also known as hospice care-which Miller provides, helps vanquish pain and anxiety, both for the patient and family members, through a combination of counseling and medication. It allows peace and love to settle in before the final breath is drawn.

"Palliative" refers to relieving pain and suffering without treating the underlying cause. In the sorts of cases Miller deals with, there are no cures. Death is certain.

So it comes down to a single question: Will an elderly person who lived an honorable life pass away peacefully or in agony? Miller's empathy for others drives him to do all he can to ensure it's the former.

The welcome he receives when he visits an elderly patient in Pingding county is always warm-a close embrace, a meeting of the eyes, a smile and encouraging words. It's much warmer than what he expected when he first undertook the quest to relieve terminally ill patients in the Yangquan area of Shanxi in 2013, together with his wife, Li Ruoxia, 44.

He has witnessed many touching moments. Even people at the end of life, who may be desperately ill, are often focused not on themselves but on the well-being of the loved ones around them, he said. Turning their own dire situation on its head, they reach out to comfort others.

Given the travel challenges of the region, including the steep and winding mountain roads of Pingding county, a visit from Miller always comes as a surprise. Sometimes, his 6-year-old daughter accompanies him, adding a bit of vivacious energy to the household of a terminally ill patient.

Doctor, teacher, friend

In the village, where people speak an obscure dialect, Miller is known as "Lao Mei".

He speaks with everyone, but especially those near death, in a friendly, conversational way-like a counselor or friend. He tries to calm the minds of the dying and settle their spirits. He holds their frail hands gently as he gives soft instructions and advice. He feels their pain in an intimate, personal way.

Wearing a brown T-shirt with a slogan on the back-"Start a conversation"-Miller presents an unconventional picture of a doctor. He loves to practice calligraphy in his spare time and occasionally demonstrates baduanjin qigong, a set of traditional Chinese fitness exercises whose roots reach back 800 years. He teaches some of the movements to patients who are able, or he plucks a string instrument to cheer them up.

But sometimes he struggles to make sense of life and death as he talks with patients whose lives are ending, especially the younger ones.

"I feel very sad about it, but I know there's nothing else we can do," he said.

At such times, a small group meeting with his wife and social workers will be convened in their workroom to vent the emotion.

Refuge for the weary

The word hospice comes from the Latin "hospitium", or guesthouse. It originally described a place of shelter for sick and weary travelers. Nowadays, it means supporting people in the final phase of life.

The idea is to address the patient's social, spiritual and emotional needs, controlling pain so that every day can be lived as fully as possible. It's a way of treating the whole person.

The hospital where Miller works as a counselor and board member, Yangquan You'ai Hospital in Yangquan, Shanxi, has a team of social workers led by his wife, and offers hospice care to terminally ill patients who have been admitted.

More than 120, ranging in age from 9 to 89, have completed their life's journey with Miller and Li helping make the final steps as pain-free as possible.

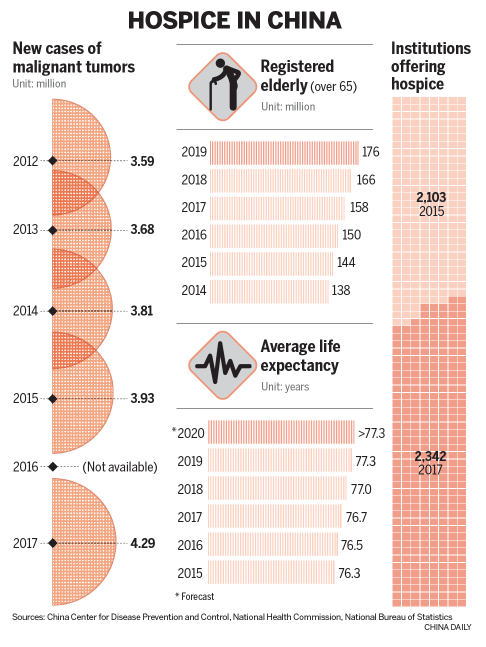

Eldercare has been recognized as a major weakness in China's social development over the past several decades. With the numbers of elderly people rising, nursing models for them have become a more prominent topic in the nation's effort to build a moderately prosperous society in all respects-especially in rural villages.

Miller's own past work sheds light on the progress of eldercare in China. In 1997, he conducted field research in Zouping, Shandong province, focused on family support for the elderly in rural areas.

Many seniors strive to be independent to minimize the burden on their families.

"But houses for old people in Zouping back then were dirty, and people had bad habits," he said. "When their hot tea got cold, they would just pour it out on the floor. Traditional mindsets can hinder development."

Change for the better

But what he observed in Yangquan in 2014, after introducing the concept of hospice care from the United States, suggested that things were changing for the better.

"The habits and customs of the rural elderly have improved," he said. "There's been a mental transformation."

The elderly have received better care as their needs have begun to be taken more seriously in the community and in wider Chinese society.

Miller and his wife pioneered palliative care in Shanxi province, and they have labored to localize hospice services.

They envision a community-based system in the future to ease the way for the terminally ill.

"Their arrival broke through the bottlenecks in our hospital," said Li Youquan, founder of Yangquan You'ai Hospital."Dr Miller helped us improve the technology of cancer screening and introduced the concept of palliative care."

According to the National Bureau of Statistics, there were more than 176 million people over age 65 in China at the end of last year. Earlier, the National Health Commission had found that more than 180 million seniors over age 60 had chronic diseases. Nearly 40 million were disabled or partially disabled.

Cultural hurdles

It has been a challenge in China to tell dying patients how to face death when it's knocking at the door. Discussions of death remain virtually taboo, as a deep-seated cultural notion holds that talking about bad things makes them more likely to happen.

So people avoid talking about terminal cancer with relatives who are afflicted by it, and they avoid planning for death, as though the refusal to talk about it will somehow hold it back.

"The result, ultimately, is the loss of quality of life and wealth," Miller said. "Families in rural areas of China have plunged into extreme poverty because of the cost of treating serious illnesses. But we're improving, and they're accepting."

In Western countries, most deaths among the elderly come after years of decline. About two-thirds of deaths occur in a hospital or nursing home.

The trouble is that terminally ill patients who die in hospital wards typically experience more pain than those who die at home or in hospice care, Miller said.

With hospice, people have the opportunity to die without pain, at peace and surrounded by loved ones.

"China has done a lot in terms of developing medical care over the last several decades, from just treating infectious diseases to handling more chronic illnesses," Miller said. "What's really needed now is a program for taking care of patients after they leave the hospital-and preventive care also."

Dying with dignity

Wang Quanlin, 51, had advanced ovarian cancer. Miller encountered her after she had been bedridden in the hospital for six months. He advised her family to take her home and provide palliative care.

For late-stage cancer patients, tumors and toxins accumulate in the body, devouring it bit by bit. Rogue cells had been eating away Wang's health in increments for four years.

Her face was round, with pale lips, and a pair of dark eyes peered like little buttons from puffy cheeks that were shriveled and dull.

Her husband had died several years earlier and her poor financial situation had led her to choose a conservative, less expensive treatment for her disease, which allowed it to ravage her body all the more. Her son, a recent college graduate, was her sole support.

At the end of her life, in familiar surroundings at home, Wang could only take short breaths. But she wasn't in pain. Her eyes were open in her final moments, gazing heavenward as if observing a celestial scene, a common occurrence, according to experts.

The hospice team of social workers led by Miller, together with nurses from Yangquan You'ai hospital, provided powerful medications to ward off pain and ease Wang's breathing. Morphine may be used, and a sedative adds to the calming effect.

Under a dim light in her home in southern Yangquan, Wang died peacefully on the evening of June 17, surrounded by beloved relatives and with her son at her side. The love in the room was palpable, unlike an impersonal hospital ward that may be shared with strangers.

For Miller, such endings are worth all the effort. There is no escaping death, but the way in which the final scene unfolds can be managed to bless the lives of all.

"What matters most is that our efforts do, in fact, help ease the pain of both the patients and their families," Miller said.

His mission of mercy, he believes, makes a difference.

Today's Top News

- Cutting edge of manufacturing boosts resilience

- Asian Cup run reignites soccer hope

- Crackdown on Chinese firms politically driven

- Mainland denounces Taiwan-US trade deal as 'sellout pact'

- Steering Sino-US relations in the right direction

- Retired judges lend skills to 'silver-haired mediation'