Tech-tonic shift: Officials become salesmen

Live-streaming is turning around the way agricultural produce is sold

One December afternoon, Wang Shuai, deputy chief of Shandong province's Shanghe county, was given a challenging task-to record a video of himself eating braised chicken and imitate the marketing style of Li Jiaqi in his live-streaming shows. And he had to eat enough braised chicken to be called a "big stomach king".

It was no mean task-livestreaming idol Li Jiaqi once sold 15,000 lipsticks in just five minutes.

Wang Shuai had reason to be worried. He had tried live-streaming before. When he first entered the studio, he was nervous and it showed. Viewers said he looked dull and failed to immediately respond to their queries.

The 30-something Wang Shuai had a lot to prove. He picked up wisecracks and internet slangs he had seen the specialists use. In the video that emerged, he is dressed in a white shirt and glasses, like any other Chinese official, and is seen devouring four braised chickens. He even says what Li Jiaqi usually does in his shows. "All you girls, your demon is coming!" he screams excitedly while digging into the meat. "Amazing! OMG! Buy it!"

The short video got 100 million hits and that week's online sales surpassed the whole year's. After over 40,000 braised chickens were sold out, raking in one million yuan in half a month, the online selling platform had to temporarily put up the "out-of-stock" notice.

Even after eight live-streaming efforts since the middle of 2019, its huge purchasing power continues to amaze Wang Shuai. He admits the influence of short videos-on platforms such as Kuaishou, Douyin (popular outside China as TikTok) and Taobao-is underestimated.

Whither deputy counties?

When Wang Shuai's video went viral, some people began doubting he was really a deputy county chief. Someone then posted a page from the local government website to prove he was indeed one, but it only led to more astonishment.

Like Wang Shuai, a growing number of deputy county chiefs in China, many from poverty-stricken regions, have shaken off their initial reluctance and walked into live-streaming studios to hawk local farm produce and help farmers increase their incomes. "The work I do in office is totally different. So, the moment I enter a livestreaming studio, I have to motivate myself to sound passionate and excited about the whole affair," says Wang Shuai.

Once the live-streaming is turned on, the officials go all out to sell their wares. Liu Chunxiao, deputy chief of Changshun county in Guizhou province, consumed a raw egg live to assure customers of its pure qualities; Du Guohui from Le'an county in Jiangxi province joked that his face covers two-thirds of the screen thanks to his hometown's eco-friendly agricultural products. Zhu Mingchun, deputy chief of Dangshan county in Anhui province, sang a song, My Chinese Heart, to show how the locally produced pear syrup had done wonders to his vocal cords.

And this metamorphosis has endeared government officials to rural folk. "They don't seem like deputy county heads any more. They are more like public servants, just what officials should be like," someone commented on social media.

And application of information technology is turning around rural fortunes like never before. During a 15-minute live-streaming session with a top influencer in May 2019, Zhu Mingchun helped local villagers sell 75,000 kilograms of nectarine for 1.5 million yuan. Such is the mad rush to buy some products that the apps sometimes introduce a countdown, making prospective buyers wait a while before they can make a purchase.

Learning on the job

The deputy chiefs are not as equipped as their professional counterparts. Wang Hongtao, deputy chief of Zhenping county in Henan province, had to once make his mobile phone rest on a teapot so as to be able to use both his hands to cook locally made noodles live.

What clicks with the audiences is the sight of, otherwise, serious officials being so informal. Wang Hongtao calls his viewers "baobao (baby)". And he live-streams even while doing research in the countryside. Once, he began live-streaming to show luxuriant weeds growing beside fruit trees and assure his "baobao" that the agricultural produce he sells them has no pesticides.

"The quality of farm produce is often suspect," he says. Such endorsement helps create trust.

Wang Hongtao began live streaming in 2017 after local orchard owners approached the government for help as their peaches remained largely unsold during rainy season.

The farmers traditionally relied on middleman who would push down prices even when the produce was of high quality.

Wang Hongtao wasn't sure he could help. "People think deputy county heads have a serious demeanor. Would they take us seriously after an image makeover?" But take him seriously they did. His live-streaming efforts saw stocks fly off the shelves. Also, the price farmers got through live streaming-which helps establish a direct link with the customers-was higher than what middlemen would give them.

Live-streaming also allows farmers to tweak supply according to demand. Following sweet potato shortage in 2018, a village Party secretary in Wang Hongtao's Zhenping county urged farmers to increase plantation area in 2019. Even the increased produce was all sold out.

Yuli county in Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region calculates online demand for its produce a year in advance. To meet demands, the county has introduced a new variety of more fertile lamb that weighs double when fully grown.

Farmers' new tool

Holding a selfie stick, He Miao, deputy head of Yuli county, was walking through the stalls at a fair on New Year's Day, peddling local specialties and tourism live. And when he began eating a block of brown roasted lamb live, the internet erupted with some 60,000 people viewing him online. Altogether 1 million viewers hit the show in a time span of three hours. He Miao is no stranger to the power of new media. He keeps himself abreast with the latest advances in communication tools.

In 2016, his single post on Weibo boosted the sales of three metric tons of jujube. But even with over 200,000 followers on social media, live-streaming videos' sale potential continues to amaze him.

"China is leading in the application of information technology," said Sun Jiashan, a researcher of cultural studies at the Chinese National Academy of Arts. It is believed that using this technology, deputy county chiefs can achieve a lot more for rural areas. And it can only get better with 5G.

In 2019, a third of lambs in Yuli county was sold online.

He Miao says live-streaming helps high-quality-and-high-price agricultural products find targeted consumers. Over half of their products made it to first-tier cities like Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Shenzhen last year.

"Urban residents yearn for a rural feel," Sun said. "Live-streaming makes them feel they are doing just what the live-streamer is doing." No wonder Li Ziqi, with her popular videos on rural life, has over 22 million followers on Weibo and over 8 million on YouTube.

And Liu Shujun, deputy chief of Chengbu county in Hunan province, over 200 kilometer away from the nearest city, usually sets up his livestreaming studio in the fields. He is shown live, catching chicken, extracting honey from beehives or showcasing the entire process from the time paddy is harvested till it reaches a dining table.

Live-streaming is also bridging the huge distances and gaps between rural and urban areas. Officials are now trying to dispel some misgivings farmers have and encouraging them to live-stream their produce themselves. Some critics say live-streaming will encourage farmers to play with phones all day. "We had to tell farmers that while they do have to use smartphones more often, it is for the sake of farming and will increase their incomes," says Wang Shuai.

E-commerce training sessions the government holds for farmers have seen full attendance. Smartphones are easily becoming the farmers' new tool. Wang Shuai said the development of e-commerce is also luring young people back to their hometowns to start new businesses, doing wonders for China's poverty alleviation campaign.

In He Miao's Yuli county, livestreaming is providing jobs to the disabled who cannot go looking for one elsewhere. E-commerce firms pay 5 yuan more for lambs from impoverished households.

Similar schemes helped pull Wang Hongtao's Zhenping county-where there are about 3,000 live-streamers-out of poverty in 2018. But some loopholes exist. "E-commerce for poverty alleviation measures require greater coordination of government departments, enhancement on credits and logistics, and large-scale production," said Hong Yong, a researcher of e-commerce at the Chinese Academy of International Trade and Economic Cooperation.

Today's Top News

- Foreign ministers of China, Egypt call for Gaza progress

- Shield machine achieves Yangtze tunnel milestone

- Expanding domestic demand a strategic move to sustain high-quality development

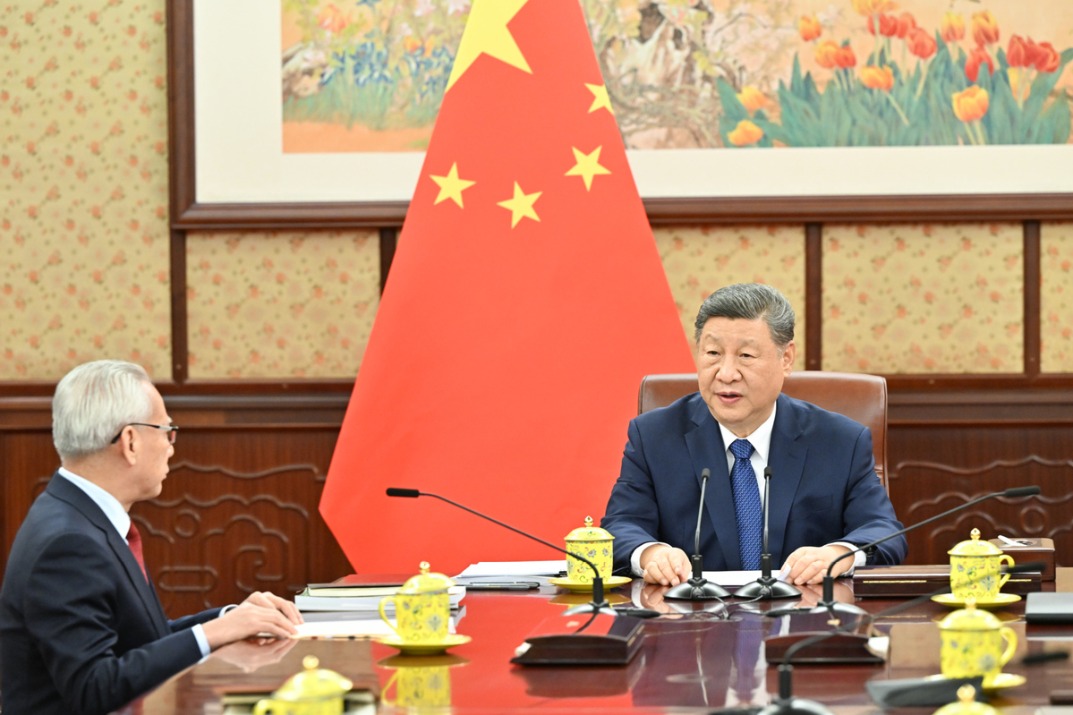

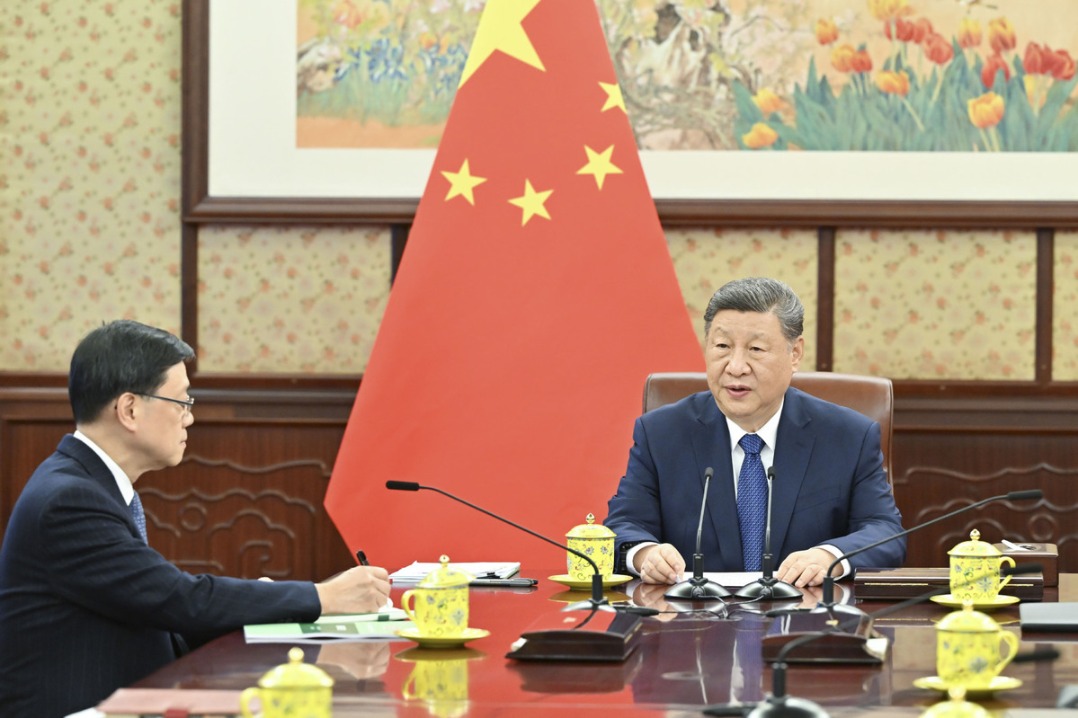

- Xi hears report from Macao SAR chief executive

- Xi hears report from HKSAR chief executive

- UN envoy calls on Japan to retract Taiwan comments