Tune in, rock out

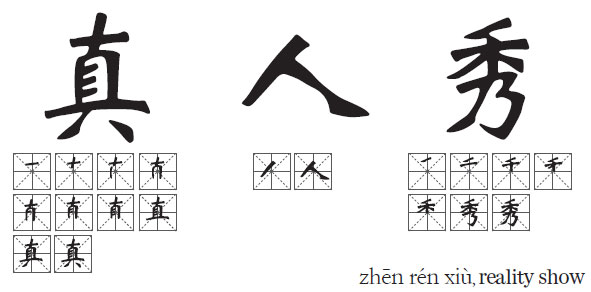

How reality TV is rejuvinating the Chinese music industry 真人秀电视节目是如何改变中国流行音乐产业的?

The lights dim and smoke begins to creep along the stage. Suddenly, a bright light beams out and a woman appears in silhouette, drawing gasps of excitement from the audience.

Another performance on I Am a Singer, a popular talent show produced by Hunan Satellite TV, starts in typical dramatic fashion.

Off to the side of the stage is music director Kubert Leung, surrounded by computers, mixing equipment and microphones. A Hong Kong native, he is a songwriter, producer and performer who has produced and written for many stars of Cantopop and Mandopop, including Faye Wong.

For the show, he manages a team of 50 or so musicians who must adapt to each performer - in this case Taiwan pop star Huang Liling, better known as A Lin, who gives a quick nod to indicate she is ready.

Leung hits the spacebar on his Macbook, the central nervous system of his band, while pony-tailed conductor Jin Haiyin raises his bow in anticipation of the first notes from keyboardist Liu Zhuo. Soon the room reverberates with the power of drummer Hao Jilun and guitarist Tommy Chan's angry power chords, and then A Lin raises the microphone to her lips.

As an industry once considered stagnant, rife with plagiarism and piracy, reality TV is breathing new life into Chinese pop music, creating an image that is fresh and marketable.

The idea behind I Am a Singer is simple: Pit former stars against one another and make the audience vote for their favorites. Each week, the least-popular contestant is axed and replaced by another has-been. This season started with seven contestants, including musicians from Singapore, Malaysia and Taiwan. The Hunan extravaganza is one of several shows that are helping to revitalize China's music industry. In CCTV-3's Sing My Song, producers choose songwriters through blind auditions and must create original music, while Zhejiang Satellite TV's The Voice of China has judges pick teams of young hopefuls to face off against each other. The Voice has featured top names such as Wang Feng and Andy Lau, and the latest season will reportedly feature Jay Chou.

While many of China's music shows derive from South Korea and Japan, the roots of Chinese pop date back to 1930s Shanghai, when American jazz trumpeter Buck Clayton collaborated with playwright and composer Li Jinhui.

Clayton and his band, The Harlem Gentlemen, had played at the Shanghai Canidrome Ballroom and regularly socialized with the likes of Chiang Kai-shek and his wife, Soong Mei-ling, until they were sacked over a bar fight. The band moved to another club in the city where, after working closely with Li, Clayton began to take Chinese folk melodies and perform them as jazz arrangements.

The US jazzman left China shortly before the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression (1937-45), but Li would continue to write music for young Chinese starlets, sending them to the top of the charts right up until the end of the Chinese civil war in 1949.

In Hong Kong and Taiwan, Li's style, known as shidaiqu, formed the backbone of what we know today as Chinese pop.

While Hong Kong and Taiwan were able to commercialize their music industries after 1949, the Chinese mainland was in a stickier predicament after the "cultural revolution" (1966-76). Intellectual property law often conflicted with the rampant economic development in the era of economic reform, and in the digital age this trend has largely continued.

The Internet has long been seen as a haven for piracy, and China's search engines are no exception.

In April 2007, a Chinese court allowed the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry to represent international record labels Universal, Warner Brothers and Sony BMG in a domestic lawsuit against search engines Baidu and Sogou for providing links to MP3 files for users in China. They wanted $9 million from Baidu and $7.5 million from Sogou. The federation lost its initial lawsuit, yet Chinese courts have since heard more than 300 cases, with the federation winning 90 percent of them.

TV music shows, which viewers often stream online, have the power to change the way music is produced and sold in China.

Not only do they generate massive advertisement revenues, they spawn subcategories of shows that continue to generate revenue simply from name-brand recognition. For example, agents for vocalists on I Am a Singer take part in a separate competition called I Am a Manager.

Now in its third season, I Am a Singer, which is based on a South Korean format, commands the lion's share of viewers on Hunan Satellite TV and nationally. According to the state media monitor CSM, more than 30 percent of all viewers in China tuned in to the season finale.

The explosion in pop music TV has not been without its problems. Super Girl China, one of the first shows to gain a large mainstream following in the country, was cancelled in 2011, as the unofficial opinion was that the text voting system was politically problematic. As such, TV shows with voting are limited to the jurisdiction of the studio audience.

How to make contestants marketable after they appear on show such as I Am a Singer also remains an issue, and competitors have even sued certain productions for infringing intellectual property rights.

Of course, there is always more than meets the eye, especially when it comes to exporting culture. The growth in Chinese pop television overseas has given the Chinese state a way of developing diplomatic soft power with the international community.

China Central Television, the state-run broadcaster, is available to view in the Middle East, Africa, Europe and the US, while the state information bureau recently co-produced a three-part show with the Discovery Channel on the "hidden" side of China.

Music television is just one thread within a wide-spanning narrative to redefine Chinese culture within the context of the modern, global consumer market.

I Am a Singer featured The One, which won the second season of the South Korean version of the show. The messages are always overwhelmingly positive - musicians coming together from across the world take part in a friendly, competitive atmosphere to bring out the best in Chinese pop culture. Singers often choose to sing songs that are familiar to Chinese audiences, and as such pay homage to China's modern age of music.

For the third season of I Am a Singer, competitors Tan Weiwei, Sun Nan, Han Hong, A Lin and Li Jian all chose music that featured minority and folk musicians, instruments, melodies and costumes as frequently as old, sappy ballads. To raise awareness of the beauty of the music from her three favorite non-Han cultures, the eventual season winner, Han Hong, played alongside Mongolian, Tibetan and Uygur musicians over the course of the season.

Through this tribute to 20th century Chinese society, and to select parts of its traditional history, I Am a Singer is, in a sense, the best of China's musical culture, translating into a unique and valuable export that is not only valued in currency, but also in influence.

As the last notes of her heart-throbbing aria leave her lips, A Lin lowers the microphone. The crowd rises to its feet, the applause thunderous. Grown men are bawling. As if momentarily dazed by the strength of her own voice, she comes back to earth, down from the metaphorical high of her last notes and turns to Leung, hand to her heart in a curt but reverent bow that shares her gratitude for such a euphoric performance and walks off the stage, a smile on her face. She's nailed it.

Leung smiles back. For a moment, he seems to be thinking about the emotional and metaphysical place her music came from. All of a sudden the lights dim again, signaling another round.

As if jolted from a pleasant dream, Leung reaches for the keyboard as the next contestant walks out onto the spotlight. One, two, three ...

Courtesy of The World of Chinese, www.theworldofchinese.com

The World of Chinese

(China Daily Africa Weekly 06/19/2015 page27)

Today's Top News

- Mainland vows stringent countermeasures against diehard Taiwan separatists

- US a 'cop' without rules seeking dominance over Latin America

- China's foreign trade up 3.8% in 2025

- 2025 a year of global health milestones, challenges

- Elderly care economy to get a fillip

- FM's Africa visit reaffirms commitment