Intertwined in China's history

An ancient fabric, silk is still greatly appreciated today and has evolved over the ages in language

A symbol of luxury, this smooth, exquisite, translucent fabric was once blamed for having corrupted the Roman Empire - a material that allowed Roman women to flaunt their exotic dresses in public. As to its origin, it was commonly believed at the time that it grew on trees far away. Philosopher Pliny the Elder, for one, described a mysterious people living on the eastern edge of the world called the Seres. He recorded in his encyclopedic work Natural History that the Seres soak tree leaves in water and then comb off the white down, which was later woven into silk. Pliny also depicted the Seres as being "mild in character" and "resembling wild animals, since they shun the remainder of mankind, and wait for trade to come to them."

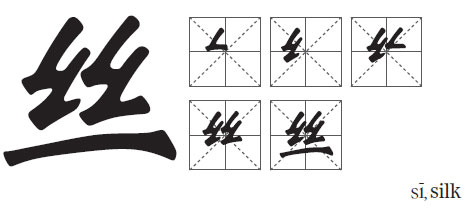

We now know that Pliny was pretty far off the mark. The word "silk" comes from the Greek word "serikos", which in turn was borrowed from the Chinese word 丝 (sī). The character's earliest form appeared as a pictorial symbol of a pair of thread bundles. Legend has it that Leizu (嫘祖), the wife of the Yellow Emperor (黄帝), or Huangdi, was the first to rear mulberry silkworms and invented the method to reel silk from cocoons. Archaeologists, on the other hand, have put the date of China's silk production at more than 5,000 years ago, supported by evidence of a piece of purplish red silk wrapping the body of an infant excavated in the Neolithic Yangshao cultural site in Xingyang, Henan province. Scholars thus hypothesize that the metamorphosis of silkworms from larvae to moth symbolized rebirth to the ancient people.

Though large-scale silk trade with the West started in the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 24), traders in Pliny's time wouldn't have been privy to the process of silk making - a closely-guarded secret in the realm. What Pliny may have been describing was people picking mulberry tree leaves to feed to the silkworms and the reeling of cocoons in hot water.

Silk production was an important part of ancient Chinese life, from which many frequently-used phrases were derived. For instance, 剥茧抽丝 (bō jiǎn chōu sī) means "to reel silk from a cocoon" and is used metaphorically to describe the action of hunting for logical clues in a confused or chaotic situation. Another common saying, 病来如山倒,病去如抽丝, states that "illness comes like a landslide, but goes like reeling silk from a cocoon", meaning that people should be patient in recovery. Another phrase, 丝丝入扣 (sī sī rù kòu), is used to describe artistic performances done with meticulous care and flawless artistry, literally referring to the weaving process where the threads are closely knit together.

A large number of related words contain the silk radical, 纟, such as in 纺织 (fǎngzhī, textile) and 缝纫 (féngrèn, to tailor). Whenever you see the 纟radical in a character, you can make a not-so-wild guess that it has something to do with textiles.

丝绸 (sīchóu) refers to silk cloth, while 丝 alone more or less represents its string stage. Therefore, 丝 also refers to strip-shaped objects that are long and soft. In the culinary world, add 丝 behind an ingredient to mean "sliced", such as "sliced potato", or 土豆丝 (tǔdòu sī ), and "sliced meat", or 肉丝 (ròusī).

Silk threads are used as strings on certain musical instruments, giving 丝 the meaning "stringed instruments", usually referring to the erhu, the Chinese lute pipa, and the zither. The term 丝竹声 (sī zhú shēng) makes up China's favorite traditional musical duo, strings and the bamboo flute, referring to "instrumental music" in general.

Perhaps inspired by the soft fabric's shine and luster, 丝 also carries with it a gentle and romantic connotation. For instance, 青丝 (qīngsī, black threads) means long black hair, usually in reference to great beauty. For the sentimental type, a drizzle is 雨丝 (yǔsī, rain threads), which conjures up the image of a world covered in haze. Poets would describe love or sorrow in terms of long-lasting threads, as in 情丝 (qíngsī, love threads) and 愁丝 (chóusī, sorrow threads).

丝 is used metaphorically in many interesting phrases, such as 藕断丝连 (ǒuduàn sīlián, the lotus root snaps but its fiber stays joined), referring to the lingering affection separated lovers have for each other. 蛛丝马迹 (zhū sī mǎ jì, thread of a spider and trail of a house) refers to clues or traces.

And, because the silk threads are extremely thin (one cocoon normally yields a thread hundreds to thousands of meters long), 丝 also describes how tiny things are, such as 丝毫 (sīháo, thread and hair), meaning "the slightest amount or degree". In the same sense, it also refers to subtle feelings or senses, such as 凉丝丝 (liáng sī sī, slightly cold) and 甜丝丝 (tián sī sī, slightly sweet).

As an ancient and revered fabric that is still greatly appreciated today, 丝 certainly has influence in China and throughout the world. Wars have been fought over it and its mysteries were hidden for centuries, but perhaps most impressively, this little fabric has evolved over the ages in our language.

Courtesy of The World of Chinese, www.theworldofchinese.com

The World of Chinese

(China Daily Africa Weekly 04/10/2015 page27)

Today's Top News

- S. Korea's ex-president Yoon apologizes to public for own shortcomings

- CPC Central Committee congratulates DPRK on WPK's Ninth Congress

- Engagement with China pragmatic amid fraying transatlantic relations

- China submits first comprehensive policy document outlining its stance on WTO reform

- S. Korea's ex-president Yoon sentenced to life in prison on insurrection

- Chinese envoy urges advancing multilateral cooperation at UN committee meeting