The Retaking of Tiger Mountain

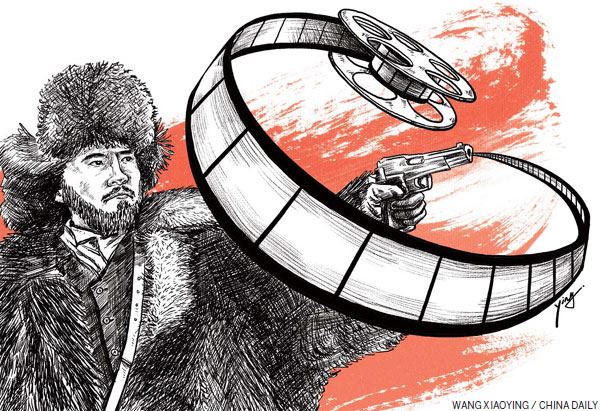

A vestige from an earlier era has spawned a new work of tremendous popularity, offering a second look at a special type of art that existed solely for the sake of politics

Before Tsui Hark's new film came out at year's end, I, like many critics, was expecting a fiasco. How likely could it be that a filmmaker reared in a freewheeling capitalist system would be able to adapt a "revolutionary" work? The values would clash violently, I presumed.

Surprise, surprise! The Taking of Tiger Mountain turned out to be a runaway hit, not only at the box office to the tune of 800-plus million yuan (more than $128 million), but also in word of mouth. The Hong Kong director has accomplished the near impossible - he has brought new relevance to a relic of the "cultural revolution" (1966-76).

To understand what Tsui has done, one has to have a firm grasp of China's cultural scene some 40 years ago. To put it bluntly, there was no culture as most would see it today. Almost all artists were sent into exile or labor camps. The whole population subsisted on only a dozen shows, which were filmed and screened repeatedly across the nation.

There is a lot of misunderstanding about the so-called Eight Model Operas. First of all, they were not born during the "cultural revolution"; most had their first incarnations before 1966. They were handpicked by Jiang Qing (Madame Mao), who essentially served as the producer, or even director, giving specific instructions on every detail, during the metamorphosis into what people later saw en masse. Even Mao himself had a hand in changing the ending of Shajiabang - by supplanting a subterfuge with a direct attack on the enemy. There's also lots of shuffling in casting as renowned performers became the targets of denunciation and were hastily replaced with younger peers.

Suffice it to say, only when the eight shows were filmed - some more than once - was it possible for them to gain a nationwide audience. They were re-adapted for the stage by local performing ensembles, often imitating every move of the screen version. Since they were the staple among a dozen films still permitted for public consumption and received numerous screenings, most people could recite every line.

Second, the Eight Model Operas were not all Peking Operas. Two of them were ballets: The White-Haired Girl and Red Detachment of Women, often shown to foreign visitors as they did not need translation. Not all of them were equally popular. Raid on the White Tiger Regiment, an opera on fighting US soldiers in Korea, was so low on the public radar that another opera, The Azalea Mountain, from a later batch of model operas, was often mistaken for one of the original eight.

Third, these works were never officially banned after the cultural revolution. The public was so sick and tired of them after a decade of extremely limited entertainment (even the word "entertainment" was frowned upon and the more politically correct "propaganda" was preferred), that they took to the plethora of music choices suddenly available. But one decade later, around the late 1980s, some started to show nostalgia for the forgotten operas. Arias and scenes reappeared, soon followed by fully staged productions. But only those portraying pre-1949 stories made a comeback because the others run counter to existing government policies, like entrepreneurs being public enemies as shown in the operas.

The debate on the nature of the model operas has since flared intermittently. Some argue they were the products of the revolution and convey its excesses and its ideology. Others contend that they embody the collective memory of a whole generation. Besides, we should not give all the credit to Jiang Qing. Many top artists put their creativity into them.

Jiang would pick filmmakers, who were released from detention and were shown films made in Hollywood - in a time when only a few top leaders had such access. They were supposed to learn Hollywood's art and craft and use it in filming the operas. Those artists had flourishing careers either before or after the revolution.

One person was widely perceived to be responsible for fusing the musical styles of traditional Peking Opera and Western orchestral music. Yu Huiyong, a musical prodigy, created the new, richer and mellower sound for the model operas. But he was not one of those suffering artists plucked by Jiang. He was a political climber who curried her favor and later gained the position of culture minister. During the post-revolution investigation, he killed himself, but his contribution to the model operas was never in question.

I grew up with these works, so I can intuit why people are so attached to them. For most of them, music heard during a certain phase of life would leave an indelible imprint, even bad music. The model operas are stridently ideological. The bad guy would not smile but grimace and the hero did not walk as much as strike heroic poses all the way. Modern audiences can enjoy them as red kitsch as every character seems to be a caricature of him or herself.

Artistically, the stories follow the rules of melodrama, with clashes between good and evil as defined by the establishment of the era. They are very easy to digest. There are occasional glimpses, such as the famous trio in Shajiabang with three characters scheming against one another, into the sophistication that went into the making of these works. Yes, much of the top talent of the country worked on them, but they were not given anything resembling a free rein. I believe art should be free, so art created in bondage, to me, does not represent the best from these artists.

I don't think people with fond memories of the operas are the same ones who want to revive or relive the revolution. The former are those in their 60s and 70s who failed to find resonance with later music, and the latter are mostly youngsters who were born after the revolution and want to vent their frustration over what they see today. The model operas are part of China's cultural legacy, an aberration that deserves to be studied rather than blindly idolized.

What Hong Kong filmmaker Tsui Hark did was a third way out. He took the story of Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy, one of the more popular of the eight, or more accurately, adapted the novel the opera was based on, and made it into a Hollywood-style action movie. The parallels between the so-called genre film and the model opera are evident: Both portray characters in black and white, but the movie is more palatable to modern sensibilities mainly because the main character, Yang Zirong, is now a lone hero with incredible smarts and devil-may-care chutzpah.

Some detractors of the movie say the historical character who became the villain in the opera, and now in the feature version, was actually not that bad. He fought Japanese invaders and was not that reckless with innocent lives. For me, these criticisms are irrelevant. This is not a documentary and a fictional film is not supposed to uncover truth beneath layers of urban myth. Tsui has to make the guy morally reprehensible to justify the raid on him. The bandit chief is still cartoonish, but in a more delicious way than in the opera.

In a sense, Tsui has substituted the old way with the Hollywood method, taking what's useful from the story and enhancing narrative elements that appeal to the young generation. He is not the first Chinese filmmaker to come up with this strategy. But with his success, there will be more efforts to mine the old field of ideological stories for the purpose of pure entertainment.

The writer is editor-at-large of China Daily. Contact him at raymondzhou@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily Africa Weekly 01/30/2015 page30)

Today's Top News

- Berlin and Beijing: Charting a course for stability and green growth

- China sees record daily passenger flow in Spring Festival travel rush

- China issues import tax incentives for sci-tech popularization

- Trump raises new global tariff from 10% to 15%

- Researchers conclude Antarctic sea survey

- Trump signs order for a global 10-percent tariff