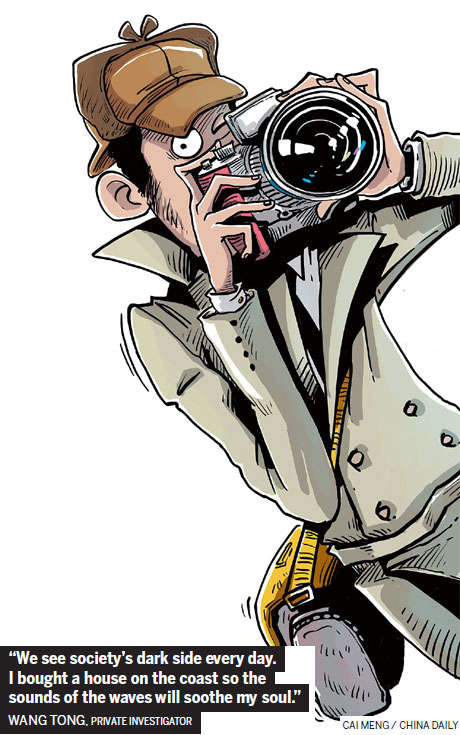

Risky business

Private investigation is booming in China, despite existing in legal limbo

Wang Tong's colleague quit after he was beaten and had a gun shoved in his face two days after becoming a private investigator. He was caught trailing a man in an infidelity case.

"We thought it was simply an extramarital affair. But the guy was a bigwig gangster," Wang recalls. "Our car and cameras were smashed. The detective was beaten, and the target put a gun in his face."

PIs enjoy little legal protection since they fall into a legal gray area - albeit one that rakes in a lot of cash.

"The profession is still without a legal status in China," Beijing-based private detective Mu Yeyue says.

"So we don't call the police when we're attacked or our equipment is destroyed. We just call it a bad day."

Wang recalls another time when he'd been scheming for days to infiltrate a well-guarded factory in Liaoning province's Anshan city in vain - until he saw a stray cat. He realized he could make the creature his unwitting accomplice.

He captured the feline and tossed it into the factory. Then he approached the guards on the guise of searching for his "pet" and was allowed in to retrieve the animal. Wang wandered around the factory under the pretense of looking for his "housecat" until he found the plastic film he was actually hunting. He extracted a small camera from his pocket and snapped a few shots. His mission accomplished, he caught the cat, thanked the guards and left. Quickly.

The Liaoning Fuer Investigation of Affairs Co private investigator had the evidence he needed to show the factory was infringing upon his client's intellectual property rights. His client had applied to patent the plastic film but discovered the products were already on the market. He suspected a technician had sold company secrets.

"The technician couldn't deny it when faced with the photos and records of his visiting the factory," Wang says. "My client recouped a great loss."

That was just one of a dozen big cases Wang and colleagues take a year. There are about 200,000 PIs in China, compared to about a dozen private detectives working for a single agency in the 1990s, insiders say. There are no official figures.

Wang entered the sector in 1993 and started his own agency a decade later. He points out detectives look different from film portrayals. "You've screwed up if people can tell you are a private detective," he says. "We try to be the most inconspicuous people in a crowd. Sometimes, we pretend to be deliverymen or cleaners to gather intelligence."

His first case was to track a doctor. He failed. "People rode bicycles in those days," he recalls. "I followed him for more than 20 kilometers on a cold winter day. My hands were nearly frostbitten. Yet I got nothing useful."

Mu says most cases he takes are economic disputes but are still risky. "Simple business disputes can be complicated, especially when the investigation involves officials or executives," says the 50-year-old former policeman. "We often receive threatening messages and e-mails, and even get knives in the mail."

Mu terminated some cases because keeping a distance from politics is a rule of thumb.

Wang says the job entails "pressure".

"We see society's dark side every day," he says. "I bought a house on the coast so the sounds of the waves will soothe my soul."

Not only has the sector's size expanded since its inception but also its scope. It deals with much more than suspicious spouses, fraud and corruption.

The industry has chiseled out China-specific contours as it has taken shape. Parents hire companies such as China Sai'an to monitor their children's school lives and performances, and to make sure they don't have a secret puppy love or hang around the wrong crowd.

While spying on spouses isn't new, more Chinese are paying for "premarital personal character investigations" from such companies as Feidu Detectives before deciding to commit. Zhao Yan Investigation Services helps Chinese parents who fear their children may be spending too much time in Internet cafes, and foreigners who are perhaps being scammed by sketchy local suitors.

"We can do anything you want," says 34-year-old Wang Dacheng, who runs an agency in Jilin province's capital Changchun.

Still, investigations generally fall into three categories - missing people, extramarital affairs and business disputes, says Meng Guanggang, who founded the country's first PI agency in 1993.

Meng points out affairs are increasingly common, especially among people in their 30s. "Some clients want to know who seduced their spouses, while others hope evidence can help them claim more property in the divorce," Wang Tong says.

Meng points out clients are "deeply influenced by gangster movies".

"They ask if we have the most advanced wiretaps, cameras and tracking tools," Meng says.

"They're disappointed to learn we use ordinary equipment. Unlike in the West, Chinese PIs can't touch criminal cases, which are the Public Security Ministry's exclusive domain. There's no need for advanced technology in civil cases. Sometimes a smartphone is enough. But IT is increasingly used in the Internet age."

Wang Tong's agency typically charges 5,000-7,000 yuan (about $800-1,150) for short and simple cases. The big bucks are in the business disputes. He made 70,000 yuan in the plastic film case, for instance.

Wang Dacheng declined to reveal his income but says it's "considerable".

"Case costs vary depending on difficulty and customers' ability to pay," he says. "Wealthy clients sometimes tip."

But satisfied customers don't translate into societal approval. Privacy infringement is one of the main concerns about the industry, Beijing Jihe Law Firm partner Wang Xiuquan explains.

Take extramarital affairs, for instance. Affairs violate the Marriage Law, but only evidence gathered in public can be used in court. Installing monitors on private property and hotel rooms are serious intrusions, he says. "It's a common practice in which private detectives track their targets and call the clients to deal with the situation when the man and mistress are inside a room," Meng says.

While bank accounts, and call or chat logs can be used in court, they can only be obtained illegally - by, say, conspiring with bank employees, public security bureaus or communications companies.

"Evidence gathered illegally can't be used in court," Wang Xiuquan points out. "But lawyers can apply to the court to collect illegally procured evidence, making it legally presentable."

Yet lawyers' ability to do so is limited, and the procedures are complicated, he says. Private investigators could play a greater role if lawyers had more rights.

Renmin University law professor He Jiahong says: "Some people use illegal methods to gather information. Their actions are no different from gangsters."

Wang, the lawyer, says a PI once attempted to blackmail his client, a company boss, after discovering the man was having an affair.

The industry should be regulated by clarifying its legal classification and placing it under such frameworks as the Forensic Investigation Law, He says.

"It'd be good if private investigators' selection and training could be like lawyers' judicial examinations," he says.

Instead, they exist in legal limbo. The Ministry of Public Security issued a 1993 directive against private investigation, pointing out PIs sometimes use powers exclusive to law enforcement. "But it's just a notice - not a law," He says.

"Economic and legal reform have increased awareness about evidence's role in the judicial system. Government departments can't keep up with the proliferation of extramarital affairs, business disputes and IPR violations. Private detectives are meeting demand."

Wang Dacheng says: "We lack legal status. But growing demand shows we have value. I don't blame anyone, but the reality is that law enforcement sometimes can't help the helpless, while private investigators can."

The industry can help the government maintain social order and reduce costs if properly managed, He believes. He prefers the term "folk investigators" because it doesn't connote privacy violations.

Mu says: "Private investigation can complement the justice system to help public security departments solve cases," he says. "If the government can guide and regulate the industry, I'm sure more cases, including criminal cases, can be solved. The police could take more holidays."

He points out the industry is better controlled than a decade before. "But we're still like underground guerillas. We work without a sense of achievement," Mu says.

"I really hope one day I can publicly identify myself as a legal private detective."

Han Junhong contributed to this story.

Contact the writer at hena@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily Africa Weekly 12/12/2014 page24)

Today's Top News

- Mainland denounces Taiwan-US trade deal as 'sellout pact'

- Steering Sino-US relations in the right direction

- Retired judges lend skills to 'silver-haired mediation'

- Are you ready for robots to roam your streets?

- Good start for new five-year plan stressed

- Nation calls for cooperation and free trade