Language should be a matter of choice

Making every college student pass a uniform test of English has created unexpected fallout, which a new testing system under consideration may rectify

The recent week has seen a spate of seemingly contradictory news stories about the fate of English language testing in the all-important national college entrance examination. First came whispers that it will be kicked out of the testing system; then it was confirmed by someone of note at a forum, even with a date attached, 2017; and finally the correction or clarification emerged that it was still under deliberation and it won't happen at least in the next three years.

But if you care to read the fine print, you'll find much in common from all the reports: Testing of English as a second language will evolve from a mandatory part of the once-a-year college entrance exam to regular testing that takes place several times a year, and yes, the earliest it may happen is 2017 - three years away. Most important, the score will be figured differently by different recruiters, depending on the emphasis of the school and the discipline of the applicant's choice.

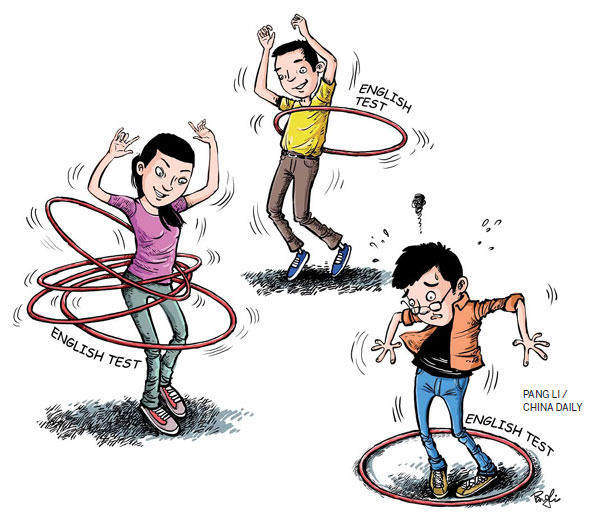

Many of my friends and acquaintances expect me to oppose this change in policy because they perceive it as a downgrading of English in the nation's testing system. They were shocked when I said I actually endorse it. Sure, I benefited from the educational system and have been using the language as a crucial part of my day job. But I don't believe people will, or should, love English or any other course with equal zeal. We all have different preferences and hobbies. When I read of Chen Danqing, the painter-educator who quit Tsinghua University, talking about some of his best fine-arts students being rejected simply because they flunked their English test, I realized that English had morphed into a stumbling block for a significant part of the nation's student body.

Just imagine the top 100 of China's artists and writers, such as Zhang Yimou and Mo Yan. Had the English test been rigorously applied to their college examination, the majority of them would have been denied an advanced education, and by extension, the chance to excel in their professional fields. Of course, nowadays college education itself is not as crucial as three decades ago in striving for excellence as it becomes available to a growing percentage of the nation's young. If you write a book that sells a million copies or make a movie that grosses hundreds of millions of yuan, it doesn't matter whether you have a college education or the ability to ace the standard English test.

The way I see it, the request for all college students to pass the same English test has not raised English proficiency per se. For most people, hundreds of hours of rote learning has fostered a culture of using English to create Chinglish. A hundred or so words in a vocabulary are not enough for any real-life use of the language. Such a limited vocabulary is good enough only for what I call "decorative English".

Decorative English is designed to show goodwill or other attitudes. When you speak a few words of English to your English-speaking host, you are essentially saying you have made an effort to be a good guest. In China, you'll see the flip side of the coin every day when you attend international events. "Ni hao" or "Dajia hao" has almost replaced "Good morning" or "Good evening" as the opening remark when executives who have just descended from their chartered planes flood you with their newly memorized Chinese words. The tactic never fails to warm the atmosphere. How can you not smile when your foreign guests overcome their jet lag and talk in a funny accent but in your language? Sometimes when I'm in a cynical mood, I even equate it with the ancient kowtow ritual.

Multinational managers probably take an hour or less to phonetically learn a few words of Chinese, but Chinese students have to spend the best years of their lives to achieve the same result. How pathetic! Other than the linguistic effect of manifesting hospitality or goodwill, there is a downside to peppering one's mother tongue with a smattering of English. It can be a subtle or not so subtle way to be snobbish - as if to say, "I know English and if you're not up to my level you'd better not join my conversation".

When I first came back to China in the late 1990s, my friends advised me to refrain from the practice, then habitual only among new returnees. I explained to them that Chinese in America insert English words in otherwise Chinese conversations not to show off, but as a necessity, because it is more practical to retain the original English for proper nouns than to transliterate them into Chinese homonyms. By no means does it speak to one's English proficiency or even preference, I said.

But in the past decade and half, things have developed in interesting ways. The ubiquity of English learning among the Chinese population, or rather, the urban young, has triggered an avalanche of unintended humor. Phrases like "people mountain, people sea" and "seven up, eight down", which are verbatim translations from Chinese, float like golden fish among certain crowds. The recent inclusion of "no zuo, no die" in the Urban Dictionary, a Web-based slang dictionary that contains seven million entries, is seen in China as a confirmation of the practice. Honestly, I do not think most of these Chinese-flavored terms are able to cross over from expatriate communities in Chinese metropolises into North America or Europe. And they would probably bring no more than a chuckle, if not a blank stare.

Whether you think this is tainting the purity of English or enlarging the sway of Chinese, I believe it is quite innocuous. The real adverse effect of a great number of people learning a little English is the illusion that you can turn to anyone for a job that only well-trained professionals can perform. Bad English is so widespread in China that some signage in big cities has become tourist destinations for Westerners. When I hear accusations that Chinese tend to be rude when talking to foreigners, I come to the defense by saying that much of the fault should be attributed to language ability, or lack thereof. Most Chinese students have learned to read, but not to verbally communicate, in English. The tones of emphasis are much harder to master for those who speak the four-toned Mandarin. If you don't know what I mean, all you need is take a bus or subway in Beijing and listen to the announcements. "Get off the train" is not wrong on paper, but with a slightly strident tone you'll feel you're being kicked off.

I once attended an opera performance of The Peony Pavilion, a classic piece with great beauty. The projected English titles essentially turned many of the passages into bawdy humor. I learned that the hack job was delivered by some translating agency, probably staffed by people rolled off the college assembly line. I told the show's producer that a certain Chinese professor spent his whole career fine-tuning every word of his English translation of this piece. This is not a job for which a four-year education is adequate preparation. Why not license that high-quality version?

China does not need a billion people who speak English badly; it needs a much smaller population whose English skill is adequate for their jobs. Let each individual decide how much English he or she should master. And the new testing mechanism is a right step in that direction.

The writer is editor-at-large of China Daily. Contact him at raymondzhou@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily Africa Weekly 05/23/2014 page30)

Today's Top News

- Xi chairs CPC leadership meeting to discuss draft 15th Five-Year Plan, govt work report

- China steps up preparations for crewed lunar mission

- China's import growth good for world trade

- HK to set up key industrial innovation site

- Major battery breakthrough paving way for EV upgrade

- Meetings promise shared growth