Scientists and looters vie for treasure

Retrieving and saving ancient heritage requires a lot more than an indiana jones swagger

After a descent of 16 meters into waters off the coast of Fujian province, Zhao Jiabin touched the sandy seabed.

The turbid water meant the maritime archaeologist's vision was restricted to just 1 meter. Apart from a group of curious shrimps attracted by the beam of his flashlight, Zhao saw nothing until a blurred reflection on the seabed caught his eye.

"My instincts told me it wasn't the reflection of shells. This was porcelain - art treasures that had remained untouched for hundreds of years," says Zhao, a veteran with nearly 20 years' experience in the field.

In the eerie, grayish seawater Zhao had discovered a wooden merchant ship believed to date from the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911).

Laden with fine porcelain, the vessel was part of the flourishing trade that helped spread Chinese culture and influence from East Asia to Southeast Asia and even to Europe.

"To be out on the ocean and come up with a 400-year-old ship makes you shiver," Zhao says. "I was so excited that my jaw dropped, and I almost lost my regulator."

However, when the unexpected sight came slowly into focus, Zhao saw that the 17th-century vessel had been ripped open by illegal treasure hunters.

Thousands of pieces of porcelain, all piled on top of each other in a huge jumble, were spread over the 23-meter-long wreck, half buried in sand and fallen rocks.

About 300 years ago, the porcelain ware - bowls, plates and jars decorated with delicate blue and white patterns - were en route to Europe, before the ship sank and became a hidden museum.

But now the porcelain had been looted, Zhao says. In an effort to grab as many pieces as possible, the looters had torn off the deck and dragged the art treasures out, causing many of the priceless relics to be broken in the process.

"The debris will soon be washed away by the current and nothing will be left," says Zhao, director of the underwater-archaeology department at the National Museum of China in Beijing. "I feel so sorry that we didn't protect the ship before it was looted. Having been overlooked and lacking many resources, the development of China's maritime archaeology has experienced many twists and turns."

Beating the looters

The biggest headaches come from looters and treasure hunters, according to Zhao, who has witnessed an illegal salvage operation firsthand.

"Dozens of fishing boats were floating above an ancient sunken cargo boat," he says. "Each had a diver working underwater. They (the looters) don't mind destroying the hull to get at the porcelain. They don't even mind breaking some of the pieces because their rarity brings a high price. All they care about is money."

Professional archaeology and commercial salvage are irreconcilable, says Zhao. Outright looters are systematically scouring the best of the wrecks in search of gold and other booty. They supply the underground art market and unscrupulous or unsuspecting collectors, but in doing so they also destroy the archaeological context that provides scholars with invaluable evidence.

Although the government has launched a series of crackdowns, in many coastal areas divers have picked many accessible wrecks clean. Now, few of the conspicuous wrecks lying in waters shallower than 20 meters are worth excavating.

"They sail out at night or on typhoon days to dodge the police," Zhao says. "One diver died because of a problem with his gear as he dug up relics of the coast of Fujian. Once, we covered a wreck with sand to hide it from looters before we left, but it was gone after a few months. Only a large piece of the bottom of the hull was left."

The researchers are competing with looters for the best wrecks, says Zhang Wei, a maritime archaeologist and deputy director of the National Museum of China. But with their limited resources and public attention, the archaeologists are falling behind in the race.

Founded in 1987, a half-century after its Western peers, China's Underwater Archaeology Research Center sent Zhang to the Netherlands to learn diving skills.

"I didn't know a thing about diving and had just two weeks of training in a swimming pool before my coach dropped me into the ocean," Zhang says. "I didn't even have my own wetsuit, so I borrowed one from other divers in the Netherlands."

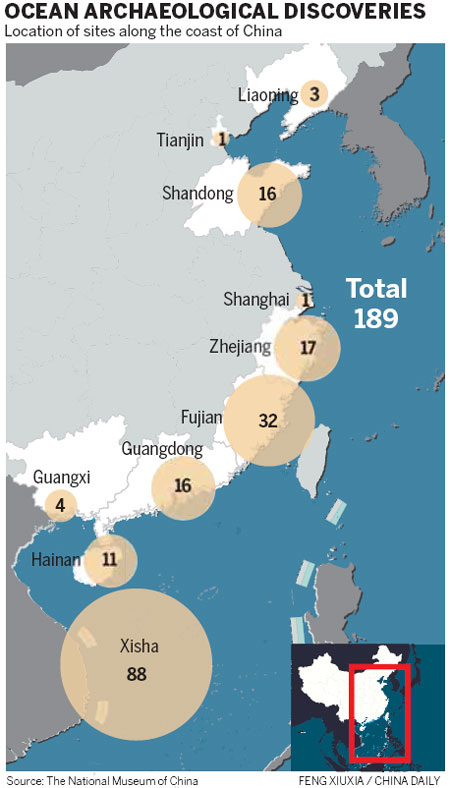

Since that humble beginning 27 years ago, the number of archaeological divers working along China's coast has risen to 55. Among them, 31 are able to dive deeper than 60 meters, but only three are capable of descending to 100 meters.

But the number of divers is far from enough to search the entirety of China's 180,000 km coastline, says the National Museum. The researchers are divided between several salvage projects, each requiring considerable time, money and personnel. Each salvage site needs a team of 10 to 12 people, including at least six to eight divers.

"We've found more than 200 wrecks that are worth studying, but our biggest problem is that we don't have enough underwater archaeologists," says Qiu Gang, head of the Hainan Museum. "Every time we find a wreck, we must protect it before the looters arrive. But we have no people available."

In addition to the shortage of human resources, Qiu stresses the importance of financial support. Training a world-class archaeological diver costs about 400,000 yuan ($65,000; 57,000 euros), and that figure does not include the cost of the equipment, which is about 30,000 yuan for each diver.

Support industry

The lack of money is not the only problem, says Meng Yuanzhao, an archaeologist at the National Museum.

"Even if we had sufficient funds, maritime archaeology is systematic work. We still need to conduct more work to build the support industry, including the related training, education and infrastructure," he says.

"In the US, the divers sail out with heritage experts who are able to recognize and preserve the submerged relics. The team also includes medical-support personnel and equipment in case of accident or illness, such as decompression sickness," Meng says. "Compared with their peers in the West, where underwater archaeology originated, China's researchers are still working in a humble environment."

In 2007, Meng was present at a salvage site in the South China Sea where more than 40 field researchers spent 56 days digging up relics from a sunken cargo vessel. Experts hope that items recovered may shed more light on 12th-century China.

Far removed from the riotous swagger of Indiana Jones, the members of the team lived on dilapidated fishing boats and wore bamboo hats, the typical headgear of the local fishermen, to avoid the burning tropical sunshine.

Mandarin ducks

Maritime archaeology is a slow and dirty business, followed by an even slower process of recording the recovered items. The divers worked on their hands and knees in 20 meters of water, sifting through the ruins of what some archaeologists regard as one of the best-preserved Song Dynasty (960-1279) wrecks.

Meng displayed a photo of one of the thousands of porcelain shards found in the wreck. Two mandarin ducks, symbols of love and peace in Chinese tradition, were vividly drawn on the surface. Untouched for nearly a millennium, the shard, which is probably part of a bowl or plate, looked like a piece of jade.

It is easy to imagine a scene from 800 years ago: A small wooden merchant vessel is plying the South China Sea, laden with tea and porcelain for European consumers. A storm whips in from the east and the boat struggles, its simple sail proving more of a hindrance than a help. Unable to navigate the narrow shipping lane, the boat is dashed against the jagged rocks that rise from the blue-green water. Its fragile hull cracks, sending the valuable cargo to the sea floor to remain undisturbed for centuries

The scene shifts to the present. While China's cultural heritage on land has increasingly benefited from national and international measures to safeguard precious items, the country's underwater cultural heritage still lacks sufficient protection, says Wu Chunming, a professor of maritime history at Xiamen University in Fujian province.

China has conducted three archaeological surveys of its land-based heritage, but only one of underwater relics. Although the survey took two years, it did not cover all the maritime areas.

In addition to rectifying the shortages of personnel and funding, Wu urged the stronger implementation of existing laws on the protection of underwater heritage.

"China has laws relating to the protection of our underwater heritage, but treasure hunting and the illegal sale of cultural relics are still serious problems," he says. "We have a long way to go to build a systematic approach to protection."

China has a rich history of overseas trade and a remarkable history of navigation, and maritime archaeology has made considerable headway in recent years, Wu says.

The country's underwater cultural heritage has yielded pottery, tools and other relics that have provided scholars with information about ship construction, navigational skills and the trading habits of earlier periods, he says.

Furthermore the lack of oxygen - which facilitates the deterioration of biological material - underwater means that the submerged cultural heritage is often much better preserved than at similar sites on land. That makes the submerged sites unique. They are time capsules.

"For our future development and success, China needs to shift from the land to the oceans," Wu says. "And to explore the seas, an understanding of maritime history is a crucial prerequisite."

Timeline

1983: In the South China Sea, British marine explores Michael Hartcher salvages 27,000 pieces of porcelain from a sunken Chinese cargo ship dating back to 1643.

1985: Hartcher salvages another ancient Chinese ship. The cargo of gold and porcelain sells for $20 million at auction.

1987: Hartcher's success leads directly to the founding of China's Underwater Archaeology Research Center, a branch of the National Museum of China.

1989: The first Sino-Australian maritime archaeology training program is founded. China assembles its first team of professional maritime archaeologists.

1990: A course in maritime archaeology is established at Xiamen University in Fujian province. Later, the course becomes a staple of Chinese university education.

1996: China launches its first maritime archaeological survey, in the South China Sea.

2001: Chinese archaeologists dive to research Nanhai-1, a 30-meter-long merchant vessel built during the Song Dynasty (960-1279) that sank off the coast of Guangdong province about 800 years ago. It was first spotted in 1987.

2007: China raises Nanhai-1 and its artifacts, including porcelain, gold and jewelry. The ship is placed in a pool-type container in the Maritime Silk Road Museum of Guangdong.

pengyining@chinadaily.com.cn

| In 2008, Chinese archaeologists undertook research into a merchant vessel built during the Song Dynasty (960-1279) that sank off the Huaguang reef near the Xisha Islands in the South China Sea. Provided to China Daily |

| Archaeologists from the National Museum of China work at a seabed site off the coast of Kenya in November. Along China's 18,000-km coastline, Chinese researchers are vying with looters for the best wrecks. Photo by Nie Zheng / for China Daily |

| Members of the salvage team wear bamboo hats as protection from the tropical sun. Wang Ji / for China Daily |

(China Daily Africa Weekly 03/14/2014 page24)

Today's Top News

- China is assessing impact of US Supreme Court's tariffs ruling

- Xi congratulates Kim on election as general secretary of Workers' Party of Korea

- US tariffs deepen Asia's uncertainty

- Mini landscapes drive village's economy

- Nation sees consumption boom during Spring Festival holiday

- Winter Olympics closes as China sets overseas medal record