Banknote buys new vision of history

| Song Mingyuan, the son of Song Jinde, a forced laborer from China, discovers his father's name on a memorial to those who died in a riot in Odate, Japan, on June 30, 1945. Photos by Wu Gufeng / Xinhua |

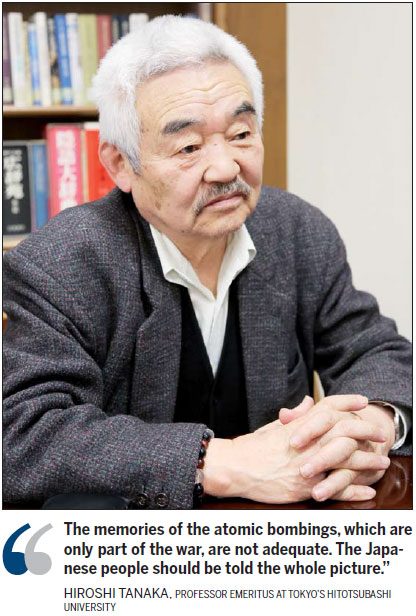

Japanese professor digs into truth of nation's past and is determined his compatriots learn the truth

For Hiroshi Tanaka, money can teach history. In his case a 1,000 yen ($10) note printed in 1963 was the window through which the professor emeritus at Tokyo's Hitotsubashi University saw for the first time a chapter in the deliberately darkened room of Japanese history.

The note carried a portrait of Hirobumi Ito, who was Japanese prime minister four times - the first, fifth, seventh and 10th - and resident-general of Korea when the country was colonized by the Japanese.

Back in 1964 when Tanaka oversaw the living quarters of foreign students, one asked why Ito's portrait was printed on Japanese money. The question caught Tanaka by surprise because he had no idea that Ito was an issue.

When he discovered the answer, Tanaka concluded that Ito's portrait on the note was inappropriate.

Ito was hated by many Koreans and was assassinated by An Jung-geun, a Korean independence activist, on Oct 26, 1909. In 1964, most of the foreign students in Japan were Korean. They had to use paper money bearing a portrait of a person they loathed. The banknote was in circulation until 1986.

"Why shouldn't Japan have taken the Koreans' feelings into consideration?" Tanaka asked, his conscience troubled.

As he researched the issue, his view of Japan's involvement in World War II was shattered.

Tanaka was born in 1937, the year Japanese troops committed the infamous Nanjing Massacre.

Chinese government statistics show that 300,000 people were killed during the six-week operation that began on Dec 13 that year.

By the time the war in the Pacific ended, Tanaka was in the third grade. At school, he was taught that the conflict began with the attack on Pearl Harbor and was ended by the use of atomic bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Moreover, the official version claimed that Japan only fought the United States. Shortly after the war, Tanaka, along with other young people, began studying English, nursing the ambition of building Japan into a US-style country.

"This is the way people of my age know about the war," Tanaka said. "Had I not got to know those foreign students, I would have lived with this false knowledge for the rest of my life."

More windows to the ugly chapters of Japan's wartime history had been opened, appealing to his better nature. Moreover, they changed him into an activist, and he has since worked to educate his compatriots about the facts of history.

Late last year, Tanaka joined many Japanese scholars and veteran diplomats to push the government to abide by what has become known as "the Murayama statement".

"Since Prime Minister Shinzo Abe took office, historical negationism has reared its ugly head in Japan," he said. "Therefore, it's necessary to raise public awareness of the importance of the Murayama statement."

In a 1995 statement, the then-Japanese prime minister Tomiichi Murayama apologized for the country's "mistaken national policy ... [that] caused tremendous suffering to the people of many countries, particularly those of Asian nations". During a recent trip to Seoul, Murayama said his statement was of crucial importance to the country's future.

On Feb 12, describing the "comfort women system" - a euphemism for the system under which women were forced to work as sex slaves for the Japanese military during the 1930s and '40s - as an "indescribable wrong", Murayama told the National Assembly in Seoul that Japan needs to resolve the issue and confront other historic wrongs.

But as Japanese politics and society appear to be moving increasingly to the right and conservatives still seem reluctant to confront their country's war record, concerns have arisen over the effectiveness of the Murayama statement.

Historical revisionism

At his inaugural news conference on Jan 25, Katsuto Momii, chairman of Japan Broadcasting Corp, or NHK, claimed that all warring nations had the equivalent of "comfort women".

The strong showing of Toshio Tamogami, the former chief of staff of Japan's air self-defense force, in the Feb 9 election for Tokyo governor suggested an undercurrent of ultraconservatism among the electorate. Tamogami, who denies Japan's war of aggression, came in fourth with 611,000 votes, or 12 percent, leading his camp to declare that a new political force had been born.

Canvassing on the streets of Tokyo on Feb 8, Tamogami said the war of aggression, the Nanjing Massacre and the "comfort women" were all fabrications. The crowd erupted into applause

The 65-year-old said he will continue to visit the Yasukuni Shrine - which commemorates leading war criminals, along with the nation's war dead - to restore pride in Japan's history. He also expressed opposition to allowing foreign residents to vote in Japanese elections.

While campaigning for Tamogami, Naoki Hyakuta, a writer and NHK governor, argued that the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal was designed to cover up US atrocities during World War II, such as the Great Tokyo Air Raids and the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He also denied that the Nanjing Massacre occurred.

Tsunehira Furuya, a commentator who also backed Tamogami, claimed that Internet right-wingers have emerged as a new political force.

Statements like Furuya's left Tanaka decidedly worried: "Erroneous views are circulating on Japan's Internet. Young people read little and get the knowledge they want from the Internet. No wonder they are under the influence of the wrong views. It's a big problem."

Chinese forced labor

While Tanaka's personal experience with foreign students was the catalyst for his interest in Japan's wartime history, his research has provided evidence of more cruel acts committed by Japanese soldiers.

Even before his retirement from the post of professor of sociology at Kyoto's Ryukoku University, Tanaka became a representative of several citizens' groups that work to support foreign residents in Japan. He has also joined a movement to help survivors and family members of Chinese people forced to work in Japan during the war.

About 40,000 Chinese were abducted to undertake hard labor at 135 sites in Japan under a 1942 decree issued by the country's wartime cabinet. Postwar Japanese governments have remained stubbornly mute regarding the responsibility for the policy. Of the 35 Japanese companies that used laborers, about two dozen are still in operation. They uniformly sought to evade their responsibilities for more than five decades until 2000, when Kajima Corp reached a settlement with the Chinese forced to work at its Hanaoka site.

During the war, 986 Chinese were brought to the Hanaoka (present-day Odate in Akita prefecture) copper mine, operated by Kajima Corp, and forced into labor. On June 30, 1945, the laborers rioted because of the poor food, living conditions and forced labor; 113 were killed. By the end of the war, 418 of the forced laborers at Hanaoka had died.

In 1987, Tanaka and like-minded Japanese formed a group to help survivors and relatives of the dead.

Odate, a city with a population of slightly more than 50,000, built a memorial upon which the names of the Chinese laborers were inscribed. The mayor has invited their survivors and heirs to the city for the annual June 30 ceremony of observation.

"Odate is the only Japanese city that has observed the event and invited the survivors and the descendants of the Chinese forced laborers," Tanaka said.

A monument to the laborers will be erected in Tianjin on Aug 8.

The Tanaka approach

"What had the Chinese laborers done in Japan to make them subject to such inhumane treatment?" asked a descendant during a trip to Japan. He wanted to know what ordinary Japanese thought about the event, and asked Tanaka to get an answer from them.

"His question helped me understand the importance of exchanges between the ordinary people of the two countries," Tanaka said.

As a result, his group set up discussions between the visitors and local people.

The professor has also participated in a non-governmental group that encourages people to reflect deeply on the massacre in Nanjing more than 70 years ago.

In December, the group invited several survivors of the massacre to tour Japanese cities, including Tokyo and Osaka, for face-to-face discussions with ordinary Japanese people about their sufferings and observations.

The guests and their hosts watched a documentary produced by Osaka TV more than 20 years ago that reflected on what has become known as "The Rape of Nanjing". The film was based on secret footage of the carnage, taken by John Magee, a US priest who witnessed the event firsthand.

The documentary shocked the Japanese viewers, who, for the first time, saw film of the massacre.

"As society tilts toward the right, it is impossible for Japan's TV stations to produce films like this one. Even so, there is no chance they could be broadcast," Tanaka said. "But we will create opportunities to allow more people to view it."

Tanaka has devoted himself to presenting a factual account of history by illustrating specific events. By doing so, he wants to enable the Japanese people to be given a truthful historical account.

But it's an uphill battle, especially because Japanese publishing houses and bookstores are winning readers by printing and selling books disparaging China and South Korea.

Some bookstores in Tokyo have set aside special sections for these books.

The comic book series Manga Ken Kan Ryu (Hating the Korean Wave) has sold 1 million copies since its publication in 2005, according to the Asahi Shimbun.

Japan's weekly magazines have begun running a greater number of articles about China since the autumn of 2010 when a Chinese trawler and two Japanese coastguard cutters collided in the waters off the Diaoyu Islands in the East China Sea. Those that print articles with headlines that contain the words "China", "South Korea", "Senkaku" (the Japanese name for the Diaoyu Islands) and "comfort women" sell well.

To observers such as Tanaka, Japan has taken the mantle of "war victim" on itself because it's the only country to have been the target of atomic bombs. It talks a lot about the adversities its people suffered in the war, but blots out the pain and damage its imperial troops committed in other countries.

Conservative politicians frequently argue that Japan was bullied into the war and fought only to liberate Asia from Western imperialism.

"The memories of the atomic bombings, which are only part of the war, are not adequate. The Japanese people should be told the whole picture," Tanaka said.

In 1970, the then-German chancellor Willy Brandt knelt before a monument commemorating the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. In 2013, Abe saluted his country's war criminals.

Despite Abe's administration allowing the historic issues to fester, Tanaka has chosen to heal the wounds in his conscience, and those of his compatriots.

He still keeps one of the 1,000 yen banknotes with Ito's portrait in his wallet as a constant reminder of a chapter of Japan's history that he will never forget and is determined that other Japanese must acknowledge.

caihong@chinadaily.com.cn

| Japanese people lay flowers at the memorial in Odate to commemorate the deaths of the Chinese laborers in the 1945 riot on June 30, 2013. |

(China Daily Africa Weekly 02/28/2014 page24)

Today's Top News

- China releases white paper on arms control in new era

- Japan must fix stance on Taiwan question

- Anti-fraud effort defends public's property, dignity

- Drive to spur SMEs gains momentum

- Huge blaze engulfs residential area in Hong Kong

- Hong Kong residential area fire gradually brought under control: HKSAR chief executive