It's hard to bottle the holiday spirit

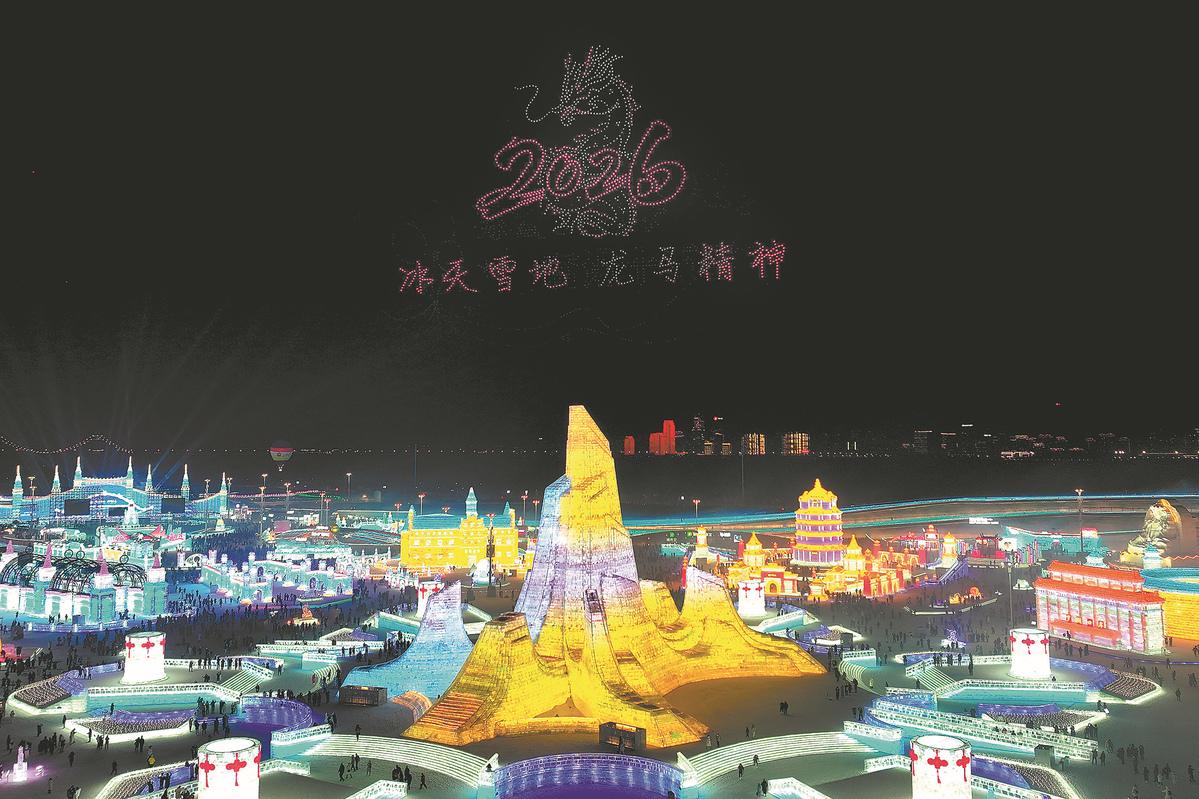

| The three-day mini-holiday for Duanwu Festival has triggered cries from some, but applause from others. Wu Jun / For China Daily |

Healthy diversity of attitudes necessary to keep Chinese Festivals relevant to modern era

There's a joke going around the web: Marx left us tons of inscrutable texts to rack our brains, and Qu Yuan gave us three days off. Luckily, it is Chinese who take care of their compatriots.

Marx, of course, is Karl, not Groucho. Every high-school and college student in China has to take a crack at his writings or at least commit long passages to memory to pass the mandatory tests. And Qu Yuan (c. 340-278 BC) was an ancient Chinese poet in whose memory the Duanwu Festival is held. Actually, it is a one-day public holiday, but, combined with a weekend, stretched to a three-day affair.

The festival falls on the fifth day of the fifth month on the lunar calendar, which means it is never fixed on the Gregorian calendar. This year it happened to be a Wednesday, June 12, right in the middle of the week. The State Council issued a decree that made the preceding Saturday and Sunday normal work days and Monday and Tuesday as days off, creating a nifty mini-holiday.

Unexpectedly, there were cries of foul. The agony of working seven consecutive days seems to outweigh the joy of a prolonged weekend or an extension of tradition-induced celebration. As I see it, you have to really hate your job to dislike this arrangement. With only Wednesday off, you couldn't have traveled farther than your local park.

I can imagine the kind of people who are detractors: it must be those who are young, stuck in dead-end jobs and live far away from their family or friends. One day of idling around is better than three days of hearing of others' journeys to the suburbs or even overseas, which will only accentuate their feeling of loneliness.

For the growing middle class, a three-day break is a godsend. They could make all kinds of plans, which would preferably take them away from urban commotion and pollution, at once relaxing their minds and body and stimulating the economy.

The length of a public holiday is a tricky thing. If it's too long, say a week, almost everyone would be tempted to travel and therefore strain the resources, such as transport, accommodation and recreational facilities, to the limit. The Spring Festival, aka the Chinese New Year, poses the ultimate challenge, and the government can do nothing about it other than building up the infrastructure (The high-speed trains are truly a huge relief).

China, the mainland that is, used to have a similar weeklong holiday for the Labor Day centered on May 1. In 2008 it was shortened from three days (turning seven days with two weekends joined together) to one day. At the same time, three one-day holidays were designated, all traditional festivals with roots going back thousands of years.

That was a giant step in the right direction: It eliminated one of the three weeklong festivals (the other non-traditional one being the National Day on October 1) and its limit-pushing headache, and at the same time it gave prominence to Chinese customs that were either taken for granted or fading from modern hustle and bustle.

Ironically, the biggest enemy for traditional Chinese holidays is not transplanted Western ones like Valentine's Day or Christmas, but the newfound affluence that has enriched almost every Chinese. In the old days we looked forward to feasting upon a plate of zongzi (rice dumplings wrapped in bamboo leaves) because we could not afford it for most of the year; children counted days to the Spring Festival because that was the only occasion their parents would buy them new clothing and handed them a red envelope holding cash.

Nowadays we can turn every meal into a New Year's Eve banquet, which essentially makes the real thing into an also-ran. We still visit our parents on Chinese New Year's Day, but instead of sitting around the table and nibbling on sunflower seeds we now sit in front of the TV and watch the Las Vegas-style gala and practice in sardonic reviews. We still send each other mooncakes for the Moon Festival, but it is more an act of consumerism than associating a moonlit night with thoughts of loved ones. We don't need to rely on the moon as we have WeChat that allows instant video chat for those living oceans apart. Technology has brought us closer and killed off the esoteric beauty of mooncake-inspired longing.

Ancient rituals were mostly born out of either inconvenience or a respect for the unknown. We didn't know what happened to those beloved who left us, so we would burn ghost money and paper-folded assets during the Qingming Festival. If we are absolutely certain our ancestors would not be using that money to buy up properties in whichever level of heaven they are now, it would look ridiculous, right? It is safe to say Chinese holidays, or holidays of most countries, are not created by scientists. Sometimes we need to resort to the metaphysical to appease our heart and soul.

Back to Duanwu, which is also known as the Dragon Boat Festival. I've never seen a dragon-boat race except on TV, let alone taken part in one, and I grew up in a place crisscrossed with rivers. There are many practices associated with the occasion and different places often emphasize one or two of them. In my hometown we don't drink realgar wine or race dragon boats, but we do eat zongzi. And the origin story for zongzi in relation to the great poet has many versions. We all know Qu Yuan was a great patriot, but few could digest his poetry, with the exception of the couple of oft-quoted lines. I had to use Yang Xianyi and Gladys Yang's English translation to decipher the Chinese original, which was written in an archaic language only linguists and literature professors can fathom.

If left to ordinary people, we would rather create a public holiday that celebrates Li Bai, the Tang Dynasty poet known for his hard drinking and, when drunk, penning some of the most sublime and also highly accessible verses in the Chinese language.

I have a vague notion that customs fall into two categories: those endorsed by the government and those ignored by the government. Official endorsement brings the gloss of media coverage, but most of the rituals tend to be staged, devoid of spontaneity while grassroots activities shared by one village or a large swath of the population often go unnoticed by everybody except a handful of diehard anthropologists. For example, survivors of the quarter million people killed in the 1976 Tangshan earthquake have made it a ritual to burn joss paper in the wee hours of July 28, a sight briefly portrayed in Feng Xiaogang's movie Aftershock. However, the officially sanctioned commemoration is to lay flowers at the memorial wall that was erected only in recent years. Which way has sustaining power?

Traditions and the holidays that celebrate them are bound to be chaotic and evolving. Once you preordain them with strict conventions, you'll risk disconnecting what is done from what is meant. In this sense, it is good that people can choose to love or hate the three-day combo deal of the past week as they see fit just as they can pick whatever fillings for their zongzi. It's the spirit that counts.

Contact the writer at raymondzhou@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily Africa Weekly 06/14/2013 page30)