highlights

Experts: Man controlled robotic hand with thoughts

(Agencies)

Updated: 2009-12-03 10:29

|

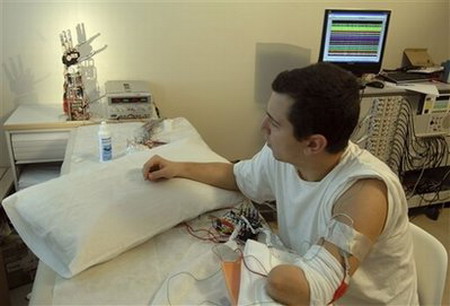

This undated photo made available from the Bio-Medical Campus University of Rome on Wednesday, December 2, 2009 shows at center Pierpaolo Petruzziello's amputated hand linked with electrodes to a robotic hand, seen at left, as part of an experiment, called LifeHand, to control the prosthetic with his thoughts. [Agencies] |

ROME: An Italian who lost his left forearm in a car crash has been successfully linked to a robotic hand, allowing him to feel sensations in the artificial limb and control it with his thoughts, scientists said.

During a one-month experiment conducted last year, 26-year-old Pierpaolo Petruzziello felt like his lost arm had grown back again, although he was only controlling a robotic hand that was not even attached to his body.

Though similar experiments have been successful before, the European scientists who led the project say this was the first time a patient has been able to make such complex movements using his mind to control a biomechanic hand connected to his nervous system.

The challenge for scientists now will be to create a system that can connect a patient's nervous system and a prosthetic limb for years, not just a month.

The Italy-based team said at a news conference in Rome on Wednesday that in 2008 it implanted electrodes into the nerves located in what remained of Petruzziello's left arm, which was cut off in a crash some three years ago.

The prosthetic was not implanted on the patient, only connected through the electrodes. During the news conference, video was shown of Petruzziello as he concentrated to give orders to the hand placed next to him.

During the month he had the electrodes connected, he learned to wiggle the robotic fingers independently, make a fist, grab objects and make other movements.

"Some of the gestures cannot be disclosed because they were quite vulgar," joked Paolo Maria Rossini, a neurologist who led the team working at Rome's Campus Bio-Medico, a university and hospital that specializes in health sciences.

The euro2 million ($3 million) project, funded by the European Union, took five years to complete and produced several scientific papers that have been submitted to top journals, including Science Translational Medicine and Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Rossini said.

After Petruzziello recovered from the microsurgery he underwent to implant the electrodes in his arm, it only took him a few days to master use of the robotic hand, Rossini said. By the time the experiment was over, the hand obeyed the commands it received from the man's brain in 95 percent of cases.

Petruzziello, an Italian who lives in Brazil, said the feedback he got from the hand was amazingly accurate.

"It felt almost the same as a real hand. They stimulated me a lot, even with needles ... you can't imagine what they did to me," he joked with reporters.

While the "LifeHand" experiment lasted only a month, this was the longest time electrodes had remained connected to a human nervous system in such an experiment, said Silvestro Micera, one of the engineers on the team. Similar, shorter-term experiments in 2004-2005 hooked up amputees to a less-advanced robotic arm with a pliers-shaped end, and patients were only able to make basic movements, he said.

Experts not involved in the study told The Associated Press the experiment was an important step forward in creating a viable interface between the nervous system and prosthetic limbs, but the challenge now is ensuring that such a system can remain in the patient for years and not just a month.

"It's an important advancement on the work that was done in the mid-2000s," said Dustin Tyler, a professor at Case Western Reserve University and biomedical engineer at the VA Medical Center in Cleveland, Ohio. "The important piece that remains is how long beyond a month we can keep the electrodes in."