After testing the beam successfully in clockwise direction, CERN plans to send it anti-clockwise. Eventually two beams will be fired in opposite directions with the aim of recreating conditions a split second after the "Big Bang", which scientists theorize was the massive explosion that created the universe.

|

|

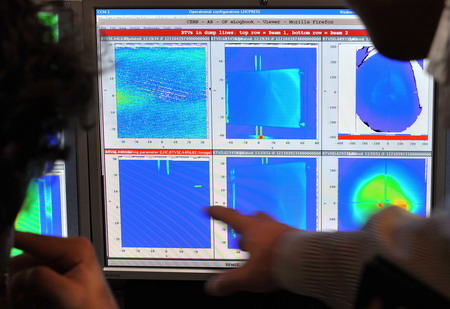

Scientists look at a computer screen at the control centre of the CERN in Geneva September 10, 2008. Scientists at the European Organisation for Nuclear Research (CERN) started up a huge particle-smashing machine on Wednesday, aiming to re-enact the conditions of the "Big Bang" that created the universe. [Agencies]

|

The skeptics' fear is "nonsense", said James Gillies, chief spokesman for CERN, before Wednesday's start. CERN is backed by leading scientists such as Britain's Stephen Hawking in dismissing the fears and declaring the experiment to be absolutely safe.

Gillies said that the most dangerous thing that could happen was for a beam at full power to go out of control. But the beam would damage the accelerator itself and burrow into the rock around the tunnel.

Nothing of the sort occurred Wednesday, though the accelerator is still probably a year away from full power.

"Today we start small," Gillies said. "A really good result would be to have the other beam going around, too, because after you've got a beam around once in both directions you know that there is no show-stopper."

The project, organized by the 20 European member nations of CERN, has attracted researchers from 80 countries. About 1,200 are from the US, an observer country which contributed $531 million to the experiment. Japan, another observer, is a major contributor, too.

The collider is designed to push the proton beam close to the speed of light, whizzing 11,000 times a second around the tunnel.

Smaller colliders have been used for decades to study the make-up of the atom. Less than 100 years ago scientists thought protons and neutrons were the smallest components of an atom's nucleus.

But in stages since then experiments have shown they were made up of still smaller quarks and gluons and that there were other forces and particles.

The CERN experiment could reveal more about "dark matter," anti-matter and possibly hidden dimensions of space and time. It could also find evidence of the hypothetical particle - the Higgs boson - believed to give mass to all other particles, and thus to matter that makes up the universe.