Op-Ed Contributors

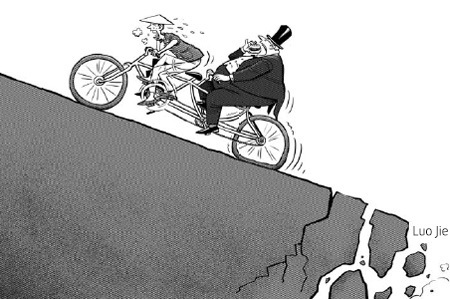

Rebuilding the globe after double trouble

By Andrew Sheng (China Daily)

Updated: 2009-12-30 07:51

|

Large Medium Small |

I was partly wrong last year when I suggested that global solutions would not be as achievable as regional and national reforms. In 2009, however, there was greater consensus at the global and national levels than at the regional level, but as recovery gathered steam, global opinion has once again diverged. The blame game is now rearing its ugly head. Instead of being praised for being the first to have a substantial fiscal stimulus to regenerate domestic and global economic growth, China is now being blamed for maintaining the yuan's peg with the US dollar that gives it competitive advantage.

Hence, there are two things that must be rebuilt if the world is to move ahead on a stable keel, one being more obvious and concrete than the other. The first is the global financial architecture, which will involve transparent rule changes and architectural adjustments that reflect the changing balance of economic power. The second is the hidden rules that underlie serious differences of views on the crises and their solutions, namely, the differences in economic thought and philosophy between the East and West.

Obviously, rebuilding physical structures is easier than rebuilding mindsets, but one cannot change without the other.

Since the US economy accounts for nearly a quarter of global GDP, the cutback in consumption will slow global growth and give time to the world to restore its imbalances both from the regional and ecological points of view.

Unfortunately, the "G3 rescue plan" of doing "whatever it takes" to relieve pain used huge public sector deficits to assume losses of the private sector. The solution replaced excessive financial sector leverage with large unsustainable public sector leverage, and instead of changing the incentives to deter excessive speculation that worsened the bubble, rewarded speculators by providing zero cost funding through the central banks. It replicated the Japanese solution of the 1990s with almost identical consequences of large carry trades, creating volatile capital flows to emerging markets.

In essence, the world is now suffering a reverse Triffin dilemma. What appears appropriate for the monetary policy of the reserve currency country is wrong monetary policy for the rest of the world. I for one would not object to a zero -interest rate-policy if it goes toward subsidizing the damage suffered by the US real estate sector, but instead most of the benefits were captured by the financial sector that paid itself more in the form of huge bonuses.

Hence, to combat the deflation in the West's bubble we seem to require a bubble in the East instead. The unspoken assumption is that if Eastern people who save were to become large spenders, replacing their Western counterparts, the world would return to its high growth path. This argument forgets that it was excessive expenditure that drove unsustainable resource depletion in the first place.

How to change this unsatisfactory global architecture is more controversial and cannot be done overnight. It is one thing to complain about a single dominant power, but to build a global central bank, regulatory system and reform international financial institutions without global fiscal structure and with a G20 of profoundly different views will be a daunting task.

My prediction is that there will be relatively little change, because there is no good unifying vision of what could be a viable alternative. To have a coherent architecture requires an architect. Sadly, we do not have anyone remotely like John Maynard Keynes to show us the way.

Hence, the real intellectual crisis today is one of obsolete economic thought, of departmental silos trying to cope with complex inter-related issues that are beyond the power of any single bureaucracy and of fragmented nations dealing with global problems that affect all humanity.

Having consumed too much, the West is now blaming the East for saving too much, forgetting that the East's savings come from producing for Western consumption at the expense of polluting its own environment and exploiting its cheap labor. If the West did not consume, the East could not have had the income to generate their savings. Both sides gained but Mother Earth lost. We ignored the externalities of ecological degradation because conventional economic theory and national statistics found them either difficult to measure or convenient to assume away.

Hence, the quick fix is not about asking the East to consume more to replace the decline in Western consumption but to think a little more long-term on how to make human development more sustainable without destroying the environment. We all need profound changes in economic thinking, including adopting measures of "green" GDP that would enable us to measure more accurately the consequences of unsustainable consumption and production.

Parallel to building these new standards of sustainable growth will be the need to rebuild our institutions.

The financial crisis was operationally an institutional crisis because the national and global institutional structures cannot cope with the externalities of financial institutions that operate internationally, but are regulated and die nationally. Rescuing these "too large to fail" dinosaurs are now beyond national resources. We need to appreciate that networked institutions are enmeshed into the global ecosystem and are not easy to remove surgically. Nor are their externalities easy to isolate or contain.

The author is adjunct professor at Tsinghua University, Beijing, and University of Malaya, and has the recently published book, From Asian to Global Financial Crisis, to his credit.

(China Daily 12/30/2009 page9)