|

|

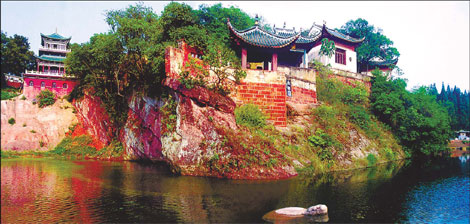

The Red Cliffs, where one of the country's best-known battles took place about 1,800 years ago, is an icon of Huanggang city, Hubei province. Du Jianxin / for China Daily

|

Song Dynasty Renaissance man Su Dongpo spent just four years in Hubei province's Huanggang city but left it with an enduring legacy.

Su Dongpo (1037-1101) was not only a man of letters but also a man of his word.

And the statesman's legacies as a scholar and poet are continuing to contribute to Hubei province's Huanggang city by creating a magnetic appeal for travelers fascinated by the place where the Song Dynasty (960-1279) man spent four years in exile.

It was one of three far-flung locations to which he was banished after incurring the ire of the official Wang Anshi by writing a poem critical of the government salt monopoly under the functionary's charge.

And it was in Huanggang, then called Huangzhou, that Su reached his literary zenith. There, he wrote most of his more than 2,300 poems and 800 letters that have survived to the present day.

It was about the settlement's Red Cliffs that he authored his best-known piece of prose, Chibifu (Red Cliffs Rhapsody).

|

The legacy of Song Dynasty poet Su Dongpo still thrives in the city of Huanggang. Provided to China Daily

|

The work commemorates the against-all-odds battle at Red Cliffs (AD 208-209) in which the direly outnumbered forces of the southern warlords Liu Bei and Sun Quan cunningly vanquished the massive military might of northern general Cao Cao. The victory sustained the national schisms that trisected the collapsing Eastern Han Dynasty (AD 25-220) into the Three Kingdoms (AD 220-280).

Su's ode to the victory is essential reading for the country's primary school students.

The cerebral scholar was born into a family of literati and passed the first of three civil service examinations with exceptional marks at age 19.

He dazzled the administrators when he satisfied perfectly a surprise addition to the test requiring an essay on Confucian philosophy to be written in ancient prose. The teenager took second place on that exam - the test administrator's apprentice took the first - and claimed the top spot on the following two tests.

He quickly rose through government ranks, ultimately becoming magistrate of eight states and holding ministerial positions in the departments of civil administration, defense and foreign affairs.

However, the up-and-coming statesman sealed his political fate when he wrote about an elderly farmer who suffered from the salt monopoly: "It's not that the music of Shao has made him lose his sense of taste. It's just that he's eaten his food without salt for three months."

Su was banished to an unpaid posting in Huangzhou in 1080.

The story of his four years in the settlement is showcased at

the Su Dongpo Museum, which will open during the Dabieshan Tourism Festival on Oct 25.

Alongside the predictable but essential displays and artifacts are several high-tech interactive exhibitions that give the museum's presentation of this ancient character a futuristic twist.

Visitors can row a pair of oars affixed to a stand set up in front of a projector that shows the digitally rendered helm of a boat navigating the waters near a cliff. The simulation allows visitors to pretend they are Su paddling along the river to his home near Chibi.

Upon completing the route and docking, rowers are rewarded with a surprise squirt of water in the face that sprays out of a hidden nozzle installed atop the oars. After taking their turns, visitors can linger to watch the startled reactions of other unsuspecting museum patrons taking their unexpected spritzes.

Near the nautical simulation is a computerized touch-screen display that allows guests to try their hands at replicating Su's calligraphy.

Visitors copy samples that flash on the screen by tracing the characters with their fingertips. Upon completing a line of prose, scribes are scored according to their penmanship.

Specimens of the calligrapher's handiwork hang on the wall nearby as additional reference points for those hoping to get a real feel of how the master manipulated his writing brush.

The museum also has several exhibits of robotic wax figures portraying scenes from the polymath's life. With a hoe in hand, one Su android tells his life story. Another depicts a folk tale in which the official tears up the deed to a poor woman's house he has purchased because he doesn't want to put her on the streets.

After leaving Huangzhou, Su was banished again to Huizhou in modern Guangdong province and once more to Hainan Island.

Having been sent to all three corners of the kingdom, the disgraced official was absolved with the crowning of a new emperor.

After decades in exile, he was finally heading to fill a desirable position in modern-day Chengdu, Sichuan province, when he died along the road in Jiangsu province's Changzhou at age 64.

While six decades of Su's life were spent outside of Huanggang, it was during his time there that he undertook his most celebrated works.

So, while he only dwelled in the settlement for four years, his legacy will live on in the city forever.

(China Daily 09/09/2010 page19)

|