The bone collectors

Updated: 2012-02-27 17:08

By Zhao Ruixue (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

Oracle bones were medicine, not archaeological relics. Thanks to the efforts of two men, these historical relics escaped the fate of being all ground up and digested. Zhao Ruixue reports from Shandong, where the museum is now home to a rich collection.

Wang Yirong was a scholar and high ranking official in the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), and we would never have known his name if he had not fallen ill one day with malaria in 1899. To make him feel better, he was given a prescription by his doctor that included "dragon bones".

These dragon bones were occasionally unearthed by local farmers, and sold to traditional Chinese medicine practitioners, who often prescribed them whole or crushed for certain diseases. Wang's doctor decided he needed a dose of ground-up "dragon bones".

Wang got curious about these so-called dragon bones. What were they? To find out, he sent a servant out to buy a whole bone, and he found some strange hieroglyphics on them. He looked closely and saw that the scratches resembled the earliest Chinese writing from almost 13 centuries ago.

His discovery shook the academic world of that time and the history of Chinese writing was, well rewritten. The dragon bones were recognized for what they really were - oracle bones used for divination.

But it was thanks to Luo Zhenyu (1866-1940), a famous Chinese antiquities collector, that the Shandong Provincial Museum now has a rich collection of oracle bones on exhibit, with some pieces that are of particular significance to ancient China.

"The oracle bones left by Luo Zhenyu contain very important historical information for the study of etymology," says Yu Qiuwei, an archeologist at the Shandong Provincial Museum.

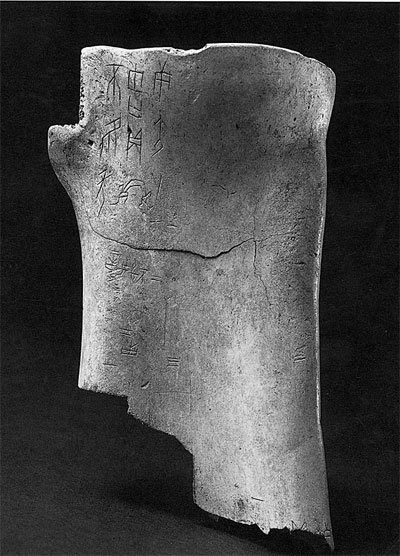

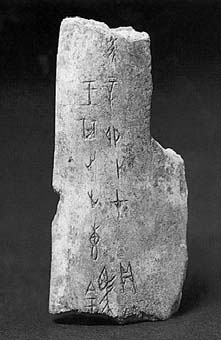

Two significant pieces in Luo's collection are the Ma Divination Bone (鎷卜骨) and the Rainbow Divination Bone (虹不韦年卜骨), both of which are from the later Shang Dynasty, from 16th century to 11th century BC.

The first bears a Chinese word "鎷" with the word for gold as a prefix. And since "gold" was also used as a general term to denote metals, it was interpreted as proof that bronzes were already popular among high-ranking officials of that period.

The Rainbow Divination Bone bears the Chinese characters that literally mean "the year that rainbows appear", which does not augur well for agriculture, according to Xu Bo, another archeologist at the museum.

"The information on the Rainbow Divination Bone is China's earliest record of rainbows," he says.

The Shandong Provincial Museum has 1,319 pieces from Luo's oracle bones collection.

They were recovered from a Japanese arsenal at Dalian in Liaoning province after China won the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression.

In the 1950s, the oracle bones were sent to Shandong and kept in the Shandong Provincial Museum.

How did Luo's collection end up in enemy hands in the first place?

Luo was the first academic who collected oracle bones being excavated near the present site of Xiaotun Village at Anyang in Henan province. This was where the capital of the Shang Dynasty was located.

After Luo died, however, his descendants sold his collection, with many of the oracle bones scattered both inside and outside China.

Another important collector was James Mellon Menzies, a Canadian who came to China in 1910, and who had gathered about 50,000 pieces of oracle bones by 1917.

He brought his collection to the Jinan-based Qilu University in 1932 when he went there to teach. In 1936, he returned home, and never came back because of the wars.

Menzies' collection later went to several museums in China, and 8,000 pieces are now with the Shandong Provincial Museum.

Unfortunately, many of those are small or crushed, and only 3,668 pieces are inscribed, according to Xu Bo.

The oracle bones are testaments to the shaman practices of the Shang Dynasty, when every important occasion involving kings and aristocrats needed divinations. The oracle bones themselves, contrary to belief, are not from dragons. They were mostly the shoulder blades of oxen, and the shells of tortoises and turtles.

During the divination ceremony, the date, the diviner's name and the question to the oracle were written on the bones, which were then heated until cracks appeared. These cracks were read as signs from the gods.

"When the kings wanted to make decisions, whether it be on national affairs or on going out hunting, they would seek an oracle for the success or failure," Xu explains. But for us, the oracle bones do not hold answers for the future. Instead, they tell us much about the past.