Art for artists' sake

Updated: 2011-12-08 13:27

By Mark Graham (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

The wealthy Belgian benefactor Guys Ullens has been supporting contemporary Chinese artists since the 1980s. Mark Graham reports.

During regular visits to Beijing, billionaire businessman Guy Ullens became intrigued by contemporary Chinese art, a fascination that developed into founding the personally funded Ullens Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing. The Belgian benefactor knows many Chinese big-name artists, having struck up friendships and bought their work on business trips to the capital city during the 1980s - long before the world woke up to the wealth of new talent emerging in China.

"I spent my weekends with art people," he recalls. "It just happened by sheer accident that the place to relax was the art community; they were not overloaded by work and had plenty of free time and I started to spend time with them.

"It was unique, it was a fun time, and they were soaking up information like sponges. They wanted to know what was happening in the rest of the world.

"They were called 'embassy artists' because the only people they would see were the cultural attachs and they would sell 15 paintings a year. They were the first to have cars, Japanese cars.

"At first, I started to buy the art as a hobby I would not fall dead from the prices, so I would buy 15 or 20 at a time. The next step was to promote the artists. Foreign museums would write to me and ask to lend pieces and I said yes, naturally. We then started to promote them in Europe and CCTV did a prime-time program about the enthusiasm for Chinese art. It grew from there."

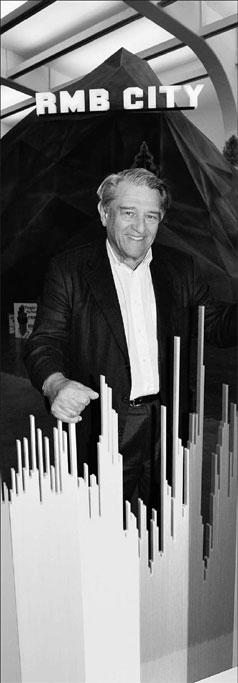

Belgian Guy Ullens helps to promote Chinese artists with his Ullens Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing. Mark Graham / For China Daily

|

|

Belgian Guy Ullens helps to promote Chinese artists with his Ullens Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing. Mark Graham / For China Daily |

After a long series of negotiations, Ullens secured space in part of a disused suburban East German-built factory, an imposing brick structure designed in the Bauhaus style.

The 798 factory complex already housed a rag-tag collection of artists and small galleries, while the debut of the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art (UCCA) in 2007 put the location firmly on the map for locals and visitors.

A rite of tourist passage for anyone vaguely interested in art is to visit UCCA and then spend time wandering around the scores of smaller galleries and coffee shops.

"Some say that is gentrified but do you want to go to a place that is dilapidated?" asks Ullens rhetorically.

"Some people didn't come here originally because they thought it was too crummy but I think it is still very bohemian. I don't think you have this in any other Western cities.

"Personally, I have a nice relationship with the Chinese artists - they are a pretty unruly crop. They say, 'Why don't you do this, why don't you do that' all the time."

Ullens bankrolls the operation, stumping up sponsorship for the artists to embark on wild flights of fantasy without worrying about the cost.

A recent show had a waterfall gushing noxiously smelly black ink, giant plastic bubbles filled with butterflies, a video installation housed in a makeshift building named RMB City, and a darkened room showing a series of black-and-white movies beamed on screens from old-style projectors.

Just how much it cost to found and fund the UCCA is a question Ullens politely declines to answer but - apart from one-off exhibition funding by fashion brands such as Dior, ticket sales from the modest entrance fee and income from T-shirts, posters and plates and the popular restaurant - every last yuan comes from the deep pockets of the founder.

It has allowed the recruitment of top professionals, such as Paris-born director Jerome Sans, an expert on China contemporary art and sometime rock musician.

Visitors familiar with art-world landmarks like the Tate Modern in London, another building with a former industrial heritage, are invariably impressed, amazed even, to find such a slickly run operation in China.

Ullens can easily afford the costs, having made his fortune from leveraged buy-outs, but is keen for the showcase project - the most important contemporary art facility in the country - to eventually be funded locally, with help from corporate sponsorship.

"We need to expand," he says.

"The Tate Modern in London, for example, is one of the most stunning (art museums) in the world. They are putting up a huge new addition and using the old fuel tanks.

"In many ways, that was a template for the UCCA. I am trying to send this message that you have more of these kinds of buildings around it, and keep them all together, it could be a new concept."

"At first we were going to have a museum and then we thought no it would be too boring."

Ullens, who is in his 70s and semi-retired, spends some of the year on his custom-built luxury yacht, Red Dragon, and makes several annual visits to Beijing, with wife Mimi, to check on his pet project.

The tycoon's family connections with China go back to the early part of the 20th century, a time when expatriates generally had a reputation for taking art out of the country, not encouraging its development.

His father was posted to China as a junior Belgian embassy attach, arriving fresh from military service in World War I.

"As a child I heard a lot about his love of China, he was very much impressed by Beijing," Ullens says. "He was a boy diplomat, aged 21 and just out of the trenches. He ran errands around China for the embassy - the Belgians were very active in railways and tramways. He met a lot of ordinary Chinese."

Ullens senior could little have imagined that his son would become a major art-world player in the dynamic new 21st-century China, building a collection of 1,000 key works.

His contribution to the development of new art is indisputable, the question now is how the UCCA will fare when the benefactor is no longer personally involved.

"This place has to be run by Chinese in the long run and we should fade out," Ullens says. "Who will take the risk? It is very common in the rest of the world. What we are trying to demonstrate to China is that you can have places like this."