Tribute to the men of down below

Updated: 2011-10-05 11:18

(China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

|

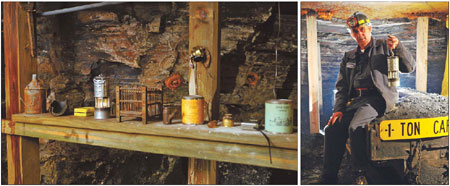

Left: Miners used, from left, lamps, a bird cage to house a canary, an oil lamp shaped like a teapot and canisters of carbide. Right: LeRoy White, who leads tours of Exhibition Coal Mine, sits on top of a coal-filled cart. A century ago, miners used picks, shovels and dynamite instead of great excavating machines. Provided to China Daily |

The life of a miner has always been tough, but no more so than in the United States 100 years ago. Timothy R. Smith reports.

Coal miners seldom get glory. Cowboys, astronauts and cops do, but how many boys strut around in coal miner helmets?

In my imagination, miners are grim and unsmiling, with futures as bleak as the tunnels they descend into, only making the news if they go on strike or tunnels explode.

Well, LeRoy White is proud to have been a coal miner, thank you very much. He spent nearly 30 years in the mines, just like his father and his grandfather before him. Now he leads tours into Exhibition Coal Mine in Beckley, West Virginia, coal country's tribute to the men of down below.

On a recent Friday, I took a seat in a rail-riding "man car" with about 19 others as White snapped on his headlamp. The car clattered forward, and he took us 281 meters underground.

Though there were lamps in the tunnel roof, the ride was dark. The tunnel is 1.8 meters high, stately for a mine, where shafts can be as low as 1.07 meters.

White drove several dozen meters down the track before stopping. He stepped from his perch and stood in front of us.

"Do you want to know the best part of this job?" He asked. "The air conditioning." True enough. Despite the 32 C day, everyone was wearing jackets: The mine stays a constant 14 C year-round.

White proceeded to give us a tutorial on the miner's grueling life.

This mine, he told us, was small by West Virginia standards and operated from 1890 to 1910. The coal miners of 100 years ago used picks, shovels and dynamite instead of great excavating machines. Each man was expected to remove six tons of coal per day. A top-notch miner could do 10.

Back then, mines didn't have lighting, save for what the miner brought along. At first, miners brought in oil lamps that looked like teapots, but these lasted only an hour at best. Later, they used longer-lasting carbide lights. White showed us one, added a few drops of water, and smoke writhed from the top of the lantern as chemical reactions inside created acetylene.

"We've got a striker like a cigarette lighter. But it don't light good," White said, snapping the striker.

"But you put your hand over it," he said, cupping his hand over the plate. "Shut the air off around it."

Poofttt! A bright flash startled everyone. White's hand backed off, and the plate emitted bright light.

Methane gas, which is a byproduct of coal, can be deadly in a mine, White said. So a fireman would come through and burn out pockets of gas with his lamp.

Most miners would drill narrow, holes into the coal with hand-held drills. After boring a few holes, they would stick in dynamite, blow the coal apart and load it into a cart.

A few people gasped at the idea of lying on a damp floor putting your whole body into cranking a drill for hours. As a boy, I was an avid hole-digger, so I thought it sounded kind of fun.

What was most shocking was how awful the coal companies treated the miners. They often paid them in company scrip, redeemable only to the coal mine and worthless in the outside world, effectively creating indentured servitude.

In the miner's home was a 1937 pay stub. The miner made $74.16 for two weeks of work. After returning a payday loan to the mine, paying for a doctor's bill, burial insurance and for the company to haul his coal out of the mine, and then buying coal to heat his home, he had $1.68 in company scrip left. As a result, he'd take out another payday loan to get through the next two weeks.

"The company provided you a hole in the ground to work," White said.