|

|

Two ethnic Miao women hospitably serve a guest homemade rice wine at a village in Jianhe county, Guizhou province, in this file photo taken in November 2009. Chen Peiliang / for China Daily

|

Ethnic rituals and languages under increasing threat as transport and communication access improves to remote areas. Hu Yongqi reports from Qiandongnan.

Tucked away in the sprawling hills and mountains of Southwest China's impoverished Guizhou province, Tonggu is a village that almost defines the word "remote".

To get there from the nearest city takes three hours on narrow, pockmarked dirt roads that would test the endurance of even the most ardent traveler.

Tonggu's seclusion has for decades played a pivotal part in protecting the rare rites and rituals of its 2,000 or so residents. Yet, like in other rural parts of China, the cultural customs of this village in the Qiandongnan Miao and Dong autonomous prefecture are today under threat.

Every new and smooth road that is built not only paves the way for incoming tourists but is also creating an "escape route" for younger generations, many of whom are leaving their heritage behind.

"The remote environment has helped many secluded villages preserve their traditions," said Cao Chunhan, director of the Qiandongnan Ethnic Museum 35 kilometers away in the prefecture's capital, Kaili.

But as this bubble slowly bursts, do villages risk losing more than they gain through modernization?

Cao thinks so. He warned that if more is not done to protect these traditions, "they will be confined to history".

The changes are already obvious in Tonggu, a predominantly ethnic Miao village known for its watercolor paintings. At its peak in the late 1990s, there were some 500 part-time painters (mostly women) producing the artwork. Today, there are just 20.

Apart from the lack of interest among young people, residents also blame the dramatic decrease on the sheer number of farmers who have left their land for better-paying jobs as migrant workers.

Ironically, talented villagers could potentially earn healthy salaries if they stuck with Miao watercolors.

Wang Shengcai, Tonggu's Party chief, said the industry has generated more than 500,000 yuan ($75,000) in revenue for the village since 2000. Works are sold either at a small gallery in Kaili or directly to tourists visiting the village.

"But as more flee villages for cities to make a living, fewer people are willing to learn the traditional handicrafts," said Yang Guangying, 75, a successful painter for more than three decades.

She revealed with sadness that her 8-year-old grandson has so far shown no interest in a skill that has played such a big part in their village's history.

After noticing that the number of artists was beginning to shrink, in September 2001 the village art association launched an ethnic painting workshop for children. It is now an annual event.

Classes run for one month and are led by locally renowned artists Chen Qilin and Zhao Yuanqiao, who coach 33 apprentices every year. Students have gone on to win 10 gold medals and 18 silver medals at prefecture and provincial competitions.

However, villagers described the workshop as a drop of water in the ocean - especially as one-third of children hang up their brushes for good after graduating.

"Painting doesn't mean money for me, so I quit," said a former student who refused to reveal his name.

Learning the language

And it is not only handicrafts that are at risk. Unique languages used only in remote regions of China could also disappear.

The dialects used in ethnic Miao and Dong villages have no written form and cultural heritage experts say they are racing against time to stop them dying out with older generations.

In the 1950s, almost every Miao could speak the ethnic language. Yet, today it is roughly only 45 percent, Lei Xiuwu, director of the Qiandongnan Institute of Ethnic Studies, said in his speech at the Ninth Senior Anthropology Forum in Kaili on June 22.

All 160 scholars in the audience agreed in a memorandum that a fundamental aspect of safeguarding ethnic cultures is to preserve their languages.

Museum director Cao Chunhan explained that, due to the popularization of compulsory education, children from ethnic groups no longer receive a bilingual education in Mandarin and their local dialects.

Youngsters living with migrant-worker parents in large cities also struggle to learn ethnic languages, usually because there is nowhere to study them.

To encourage a greater use of local dialects, Lei suggests authorities develop ethnic tourism.

Xiao Qianhui agrees. As a visiting professor of tourism with Nankai University in Tianjin, he has been helping Qiandongnan to better cater to visitors for three years.

"The prefecture has a great advantage in its ethnic diversities and unique ecological environment," he told China Daily, "so tourism should be promoted to improve the living standard and preserve the traditional culture."

Qiandongnan is home to about 1.7 million ethnic Miao and 1.3 million ethnic Dong residents, making it an area rich in heritage.

A total of 39 traditions are already recognized as intangible cultural heritage at national level, with another 124 listed by Guizhou province. Experts say that all have the potential to attract tourists, such as the famous Dongzu dage, grand choirs of Dong singers.

"The traditions (already recognized) are only a few outstanding examples of our diverse cultures," said Su Zhourong, the prefecture's director of intangible cultural heritage. "We have to make use of these invaluable resources."

She said her office is now applying to the United Nations to recognize Miao traditional costumes as world cultural heritage.

Official tourism figures show that Qiandongnan received 14 million visitors in 2009, generating more than 10 billion yuan in revenue. The peak time was during the National Day holiday week in October, when residents earned in excess of 4.8 million yuan.

Turning to tourism

Mandong village, which is 45 kilometers from Kaili and home to 1,700 Miao people, is already reaping the benefits of using its traditional industry to develop tourism.

Women here have been weaving for more than a century. Using various fabrics and silk, they immerse their products in a dyestuff abstracted from the root of a indigenous tree, then air them out in sunlight for several days. The whole process takes about 10 days.

"The loom is one of my good friends," said Pan Ying, 46, as she pinned her hair into a knot at the back of her neck in typical Miao style. "We have worked together for more than 25 years."

Even as late as the 1990s, almost 100 percent of the garments worn by villagers were homemade. Most products that run off the looms now, however, are sold to tourists.

"Many visitors are attracted by our traditional culture, which has been well preserved," said Pan, director of the village's women's committee, who explained that she weaves with the same machine her mother used for some 50 years.

For weavers in Mandong, the tourism industry that has been gradually developed since 1983 represents an extra 5,000 or 6,000 yuan a month, roughly one-third of the average income for each household.

Although business opportunities abound, the changes have failed to convince many of the village's young people to take up the handicraft.

Like in Tonggu, the lure of the big cities is proving too strong.

In the past, weaving was "a skill girls needed to have before they got married", said Pan. But things have changed and in the past two decades the number of women working the looms plummeting from 700 to just 200.

|

Pan Ying, 46, in Mandong village has been weaving for more than 25 years. The loom she uses is the same her mother used for about five decades. Hu Yongqi / China Daily

|

|

Young Miao women greet visitors at the entrance of their village with bull horns, which are traditionally used to hold rice wine. Chen Peiliang / for China Daily

|

|

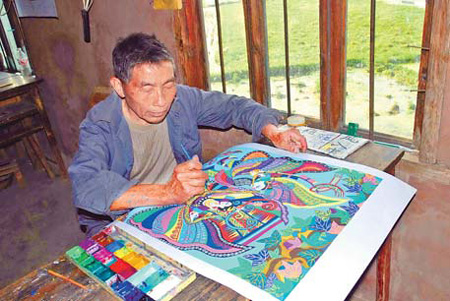

Zhao Yuanqiao, an artist in Tonggu village, puts the final touches to his watercolor painting. Zhao is one of the few remaining artists in the village. Chen Peiliang / for China Daily

|

(China Daily 11/03/2010 page1)

|