Economy

Tough time for towns where mines run dry

By Hu Yinan (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-04-16 07:42

|

Large Medium Small |

|

|

|

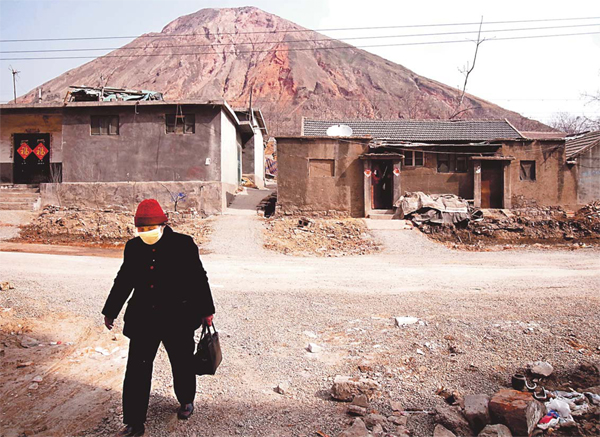

A resident walks along the barren and rubble-strewn streets of Zaozhuang, once a major mining base in Shandong province, where local offi cials are shifting towards a green economy. PHOTOS BY ZHANG TAO / CHINA DAILY

|

Efforts to find new pillar industries face a multitude of challenges, say experts. Hu Yinan reports from Shandong.

Thunderous explosions rock Bian Shuwen's home every afternoon. As each blast violently rattles his windows for seconds at a time, he becomes that little bit more convinced these tremors will ultimately cause his house to sink into the ground.

But like millions of others across China who live beside underground and open cast mines, the experience is bittersweet for Bian. Although he knows the iron ore pits in his native Nanwudong village, Zibo in Shandong province, have a severe environmental impact, he also recognizes they provide vital and, sometimes, well-paying jobs.

Ask many of his 1,300 neighbors what they fear most besides their homes collapsing and the majority will say it is the thought of these natural resources eventually drying up.

"I'm too old to work (in the mines) but the kids do earn some handsome cash," said Bian. "But I am worried about things in the future. I don't know how much long-term damage these industries are doing to our homes."

|

|

Zibo in Shandong province is one of the cities that depend on mining natural resources. |

Yet as coal and iron ore supplies diminish, communities that rely on them for employment are being forced to find new pillar industries.

The situation is particularly urgent in the 44 cities so far classed as "depleted in primary resources" by the National Development and Reform Commission, the top economic planning body.

In a recent report, the commission said 50 of China's 390 mining towns have already run dry, leaving three million miners jobless and affecting about 10 million more people.

The State Council has been helping the nation's 118 resource-dependent cities adopt low-carbon economies since 2007, with resource-depleted cities receiving central government funding to spend on shutting down illegal mines, boosting employment and enhancing environmental protection.

The money is also used to relocate or compensate people living near dangerous mine shafts.

The amount of funding each city receives varies. Although no official statistics are available, Jingdezhen, which was one of the 44 cities given "depleted" status by the National Development and Reform Commission, could potentially get as much as 1 billion yuan ($145 million) over four years, according to a report by News Magazine last year.

Local governments are desperately working on how to fill the void left by mining, and have already attempted to develop tourism and have built coal chemical plants. However, these experiments have so far achieved little success, say analysts.

In Zaozhuang, a city in Shandong that actually gained its name in the late 19th century from a coal mine, the restructuring of its core industry is well under way, according to mayor Chen Wei.

Its coal chemical bases are already among the most competitive in the country, while tourism is booming thanks to the reconstruction of two key sites that commemorate heroic acts during the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression (1937-1945), he said. (The city is famous for a band of fighters known as the "railway guerrillas" and Taierzhuang, where the Kuomintang army won a decisive battle over the Japanese in 1938.)

|

|

A street corner in Zaozhuang, where most coal resources were depleted in the 1990s. |

However, Yang Weisheng, a former official with the Zaozhuang bureau of mines, who now serves as a political advisor to the local government, disagreed.

"We're at a point where we have exhausted our resource advantages and failed to foster new advantages in the process. The restructuring hasn't been going very well because there is no industry (other than coal) that could lead this city," he said.

And although tourism may offer the potential for growth, Yang said it will never be the city's pillar industry.

"We're still heavily dependent on coal. Crude coal costs 200 yuan a ton but can sell for four times that price. As long as there's still coal down there, of course people will do whatever they can to be in the business," said Yang, who is a member of the Zaozhuang committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference.

As natural resources in the east of Zaozhuang were depleted in the 1990s, its mining industry turned westward to Tengzhou, a prefecture-level city under its jurisdiction. Now surrounded with coal mines, Tengzhou accounts for more than 70 percent of Zaozhuang's economy.

"The coal industry is thriving in Tengzhou but when you're young, you ought to think ahead for what might happen when you're old," said Yang, who believes that the city's ambition to restructure its coal industry is essentially more of an upgrade.

"To excel in the coal chemical industry, we need plenty more water, electricity and coal than before," he said, adding that to truly restructure its economy, Zaozhuang should take time to shut down illegal shafts, relocate affected residents and gradually find and shift to another pillar industry.

Government funds intended for relocation projects in Zaozhuang are twice as much as the investment made in the city's coal chemical projects, according to Chen's transformation initiative.

Meanwhile, authorities across China shut down more than 13,000 illegal mines between 2005 and 2009, show figures released by the State Administration of Work Safety.