|

CHINA> National

|

|

Joining hands and land for a better future

By Wang Zhuoqiong (China Daily)

Updated: 2008-11-21 07:47

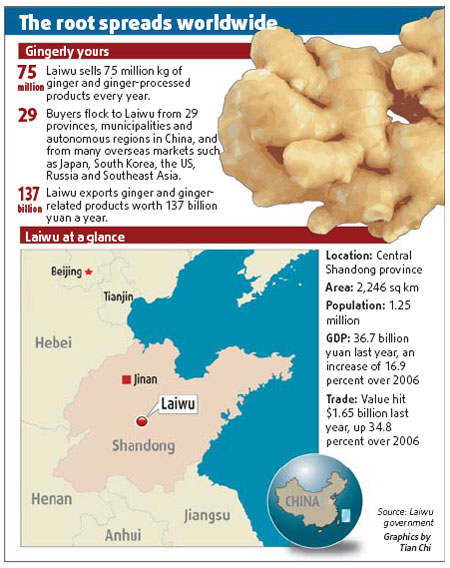

Li Changyou uproots a leafy plant with a ginger the size of a rugby ball. The ginger from the farm in Gongjiazhuang village, Shandong province, can soon land on the shelves of British supermarket giant Tesco and other supermarkets in European Union countries. The 44-year-old works for Laiwu Manhing Vegetables Fruits Corporation, which last year acquired the land-use rights of almost all the farmland in Li's village. Last month, the central government encouraged farmers to transfer their land-use rights to develop large-scale agriculture, improve efficiency, increase production and raise farmers' income - in short, raise the living standards of rural people. "The land-use rights market has existed for many years," says Han Jun, director of the State Council Development Research Center's (DRC) rural economy department. "But only 5.68 percent of agricultural land has been transferred so far." That's why the new policy does not mean there'll be a rush across the country to transfer land-use rights. Nevertheless, the new policy is widely considered the most important since the establishment of the rural family household responsibility system in 1978. Farmland is owned collectively in China but allotted to farmers in small plots on long-term leasing contracts, which usually are 30 years. But with the rural-urban income gap widening (some experts say the ratio is 1:3), the government has issued favorable polices, such as lifting agricultural tax and increasing the subsidy to farmers growing grains, to develop rural areas. The company, the country's second largest ginger exporter, however, began acquiring land from farmers in Gongjiazhuang and three other villages in Laiwu municipality a couple of years before the new policy was issued. Large-scale, standardized farming has enabled the company to not only increase output, but also lift its food safety level. Hence, its products are even exported to developed countries at prices 10 times higher than they would fetch in the domestic market. Gongjiazhuang, home to about 3,000 people, lies in a mountainous terrain, so development took time to reach it. It used to be a village of houses with weather-beaten tiled roofs and gray walls. Farmers either went to work in the fields, or migrated to cities, leaving a few women, elders and young children at home. The situation started changing about three years ago. Before Spring Festival in 2006, Gongjiazhuang was split into two camps: one-third of the families agreed to lease their land, with the rest being adamant not to because they doubted the fate of the deal. "It was very difficult," says Shen Yulu, 54, the village director, who began going from door to door to mobilize the villagers to lease out their land. "There was no precedent of large-scale transfer for the villagers." They had been growing ginger, garlic, corn and peanuts on their separate plots for years. That's why many of them were reluctant to transfer their land-use rights. "We had been farming all our life," Li says. "Farmers were worried whether the plan would work out. 'If you take our land away, what will we do?' they said." To allay the villagers' fear, the village committee stepped in as warrantor. "We told the reluctant villagers that 'if the company didn't pay, we had the right to call off the deal'," and that the 10-year lease would be reviewed annually, says Jia Chuanying, elected Party secretary of the village last year. To convince the adamant farmers, the company began a pilot project on 40 hectares of transferred land, using standardized farming, irrigation and natural fertilizers. "It was then that the reluctant farmers started changing their mindset," Liu Jianzeng, the company head, says. "They knew the small plots would never produce more money." The result: by 2008, about 80 percent of villagers had transferred their land-use rights. "Some of those who have not done so are now eager to join," Liu says. So much has changed that Li is now the leader of a team of 40 farmers growing ginger. The 600,000 yuan ($87,841) the company paid to the village committee as management fee for the transfer "has solved many problems", says 45-year-old Jia. The village committee used the money to pay for road construction, tree-planting and other projects. There are two marked changes in the village, Jia says. With a rise in farmers' income, disputes among villagers, all too common earlier, have become fewer. And vendors' business is booming. "When people have extra money, they buy things So snack vendors and fruit-sellers see their products being sold in no time." By the end of this season, the villagers would have earned more than 3,000 yuan each - add to that the rent for transferring their land-use rights. Li, for instance, gets 4,200 yuan a year for that. "It is a good deal," she says. "Before, I could make only about 200 yuan per mu (667 sq m) a year by growing corns and peanuts on my plot." The Laiwu company has acquired about 180 hectares of land in Gongjiazhuang and three other villages. Last year, it produced about 30,000 tons of ginger and 50,000 tons of garlic. But raising output is not its only goal, for it pays equal attention to food safety and product quality. "If chemical fertilizer is sprayed on a plot, not only the ginger, but also the soil will be ruined," Liu says. The 44-year-old started a pilot food safety project with the Laiwu municipal government after he was laid off from a local government-affiliated foreign trade company. "If you want to get into the foreign market, there is only one thing to do - meet their quality standards," he says. The company has set up a lab at the cost of 20 million yuan, and built a duck-breeding farm to make its own non-chemical fertilizer. Growing ginger may not be a difficult exercise, but the method followed, fertilizer and seeds are vital in large-scale farming to guarantee food safety, Liu says. That's precisely why he has hired about 20 technical personnel to train the farmers in the art of growing more and healthy ginger. Since the company is also cost-conscious, it pays the village committee to find capable persons to lead the farmers' teams. "That saves us from hiring extra hands also, the leaders know the capabilities of the team members because they are from the village, too," Liu says. "But the committee has a say in employment and appraisal." The success of Gongjiazhuang will take time to be spread across the country. Han, of the State Council DRC's rural economy department, says it could take decades given the size of the country and the population in rural areas. The key to the reform is strengthening farmers' rights - the guarantee of voluntary transfer and ownership of profit. Plus, the government has to ensure that after the right to use a farmland is transferred, the person or company acquiring it uses it strictly for farming. Since land-use rights transfer is market-oriented, the role of the government should be as a rule maker, a watchdog and service provider, instead of a participator, Han says. If the country wants to ensure the food security then it is very important that a fixed area for grain farming is mapped out and non-farming industries are prevented from setting up plants in that area. Back in Gongjiazhuang, where a successful beginning has been made, farmers are becoming restless. They are now free because they don't have to till their farmland and are looking for work to earn some extra money. Forty-five-year old Liu Zhengcui juggles between home and the forage processor factory the family runs. She is raising some rabbits at home, too. Earlier, Liu's husband used to move to the city to work as a construction worker. But now, she says, he may not have to do so. Why? Is the family making that much extra money after transferring its land-use rights? Liu, a tall and slender woman, doesn't answer. But her smile says it all.

|