|

CHINA> Profiles

|

|

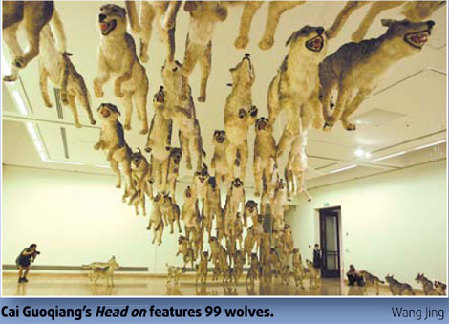

Bang on target set by 'gunpowder artist' Cai

By Zhu Linyong (China Daily)

Updated: 2008-08-26 10:05 Parents helped light the fuse Cai Guoqiang was born in 1957 in Quanzhou, Fujian province, a meeting point of different cultures when the Maritime Silk Road started in the sixth century. His father Cai Ruiqin, a historian who loves traditional brush painting and calligraphy, trained him in classical Chinese art and literature as well as Chinese kungfu.  The "cultural revolution" broke out in 1966 when Cai was 9. Although Chinese society was really closed during that period of time, "there were two windows for me to explore the world", he recalls. One was from his mother and grandmother, the unseen and invisible world, represented often in Taoist and Buddhist theories and practices. Still, as the exhibition title I Want To Believe (originally from the X-Files movies) for the Beijing show suggests, Cai admits he has "a lot of curiosity about the unseen force and invisible things". "I want to believe there are a lot of possibilities in the universe that we may not be aware of. It is like a time tunnel to go through, to go beyond the social system and boundaries of nations to make you free and to escape from them," says Cai, who in the early 1990s turned these ideas into gunpowder drawings such as the Project for Extraterrestrials series. The other window to the world came from his father, who managed a State-run bookstore in Quanzhou. Cai thus gained access to translations of Western literature forbidden to the general population during the "cultural revolution", reading such books as Waiting for Godot and Death of a Salesman. A curious and rebellious Cai decided to seek art forms different from classical Chinese art when he grew up. In 1981, he enrolled in a stage design course at the Shanghai Academy of Drama, where he picked up his sense of staging and drama for his later large-scale installation and performance work.

Since 1984, Cai has experimented with gunpowder, at first simply emptying those beloved firecrackers from his childhood. He'd place the powder on a painting and light it, which left areas of the canvas charred or smoky. He moved in 1986 to Japan where he was fully exposed all sorts of Western art trends and new ideas. But he chose to carve out his own niche by refining his techniques for gunpowder art, carefully controlling the gunpowder explosions on panels of fibrous paper, which created textures of crusty burns and softly luminous shadows. In Japan, he also created large-scale public art events that not only used explosives but involved social mobilization, calling on crews of art volunteers. Gunpowder drawings and explosion events later became his trademark. He is sometimes addressed as a "gunpowder artist". Cai's work is "hugely intuitive and conscientiously analytical", says Thomas Krens, director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation and co-curator of the exhibition. "His large-scale gunpowder drawings and site-specific explosion events demonstrate a spectacular fusion of the science and art of transformation, and propose the processes of destruction and change as radical conditions for reality, and hence creativity." However, Cai has tried many other art genres and materials. "What genres and materials you use do not matter so much," he says. "What really matters is your artistic concept and a perfect combination of good idea and good visual representation.  "It's like an alchemist who, with ordinary materials, churns out something different and wonderful." In Cai's view, each of his items is "like a dialogue between me and unseen powers, like alchemy". But he admits his work also aims to establish a dialogue between different cultures. As an overseas Chinese artist, Cai, like many of his contemporaries, faces such problems as the ambiguity of cultural identity but he retains a strong affinity to his Chinese roots. He admits he has been constantly inspired by rich Chinese cultural legacies, ranging from classical art, historical and folk tales, to Taoist and Buddhist philosophies, and even traditional Chinese medicine. But more importantly, "my Chinese cultural background has endowed me with a sharp sense of openness, tolerance and ability to absorb other cultures for my own purposes", he says. |