Carl Crook has a foreign face, but Mandarin is his mother tongue.

The Briton was born in Beijing in 1949, the year the People's Republic of China was founded.

The 58-year-old introduces himself as "a contemporary of the New China" in recognition of the fact that his life story includes many of the experiences that defined the lives of most Chinese people his age - from the "cultural revolution" to economic reform.

In fact, Crook could be one of the most informed foreign witnesses of the changes that have taken place in China in recent decades.

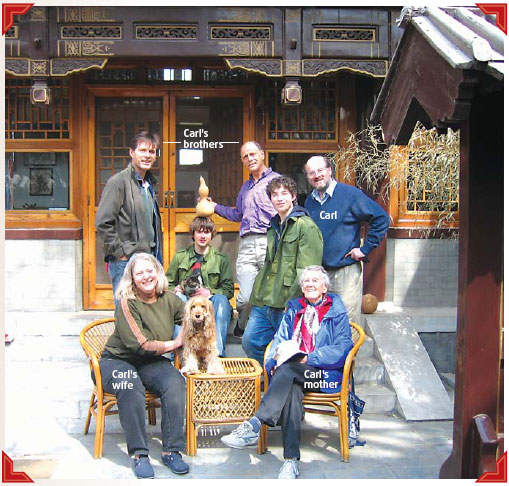

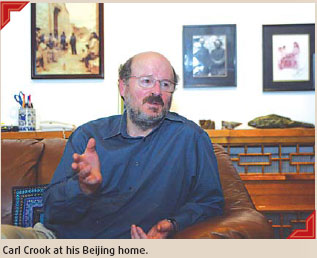

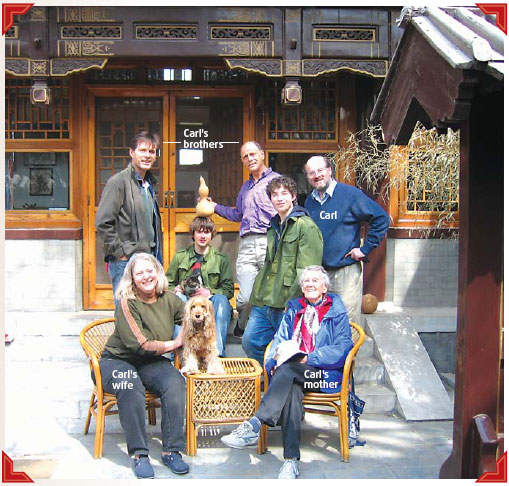

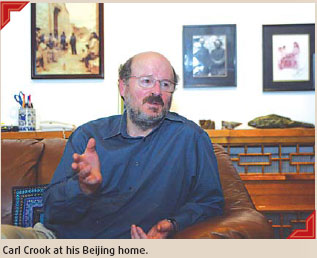

This Beijinger and his American wife live in a traditional quadrangle dwelling that is now surrounded by Western-style residential high-rises. Their 450-sq-m house stands out for its low profile.

The living room, with its many books, CDs, blue and white porcelain, and Chinese-style furniture, is a temple to Chinese culture. And though Crook is the managing director of the Montrose Food & Wine, no wine can be seen.

Several faded, blown-up photos of Crook's parents dressed in uniforms of the Eighth Route Army led by the Communist Party of China during the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression are a testament to his family's connection to Chinese history.

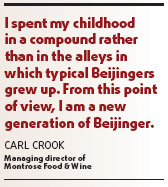

Any story about the Crook family's life in China must begin with Carl's father, David.

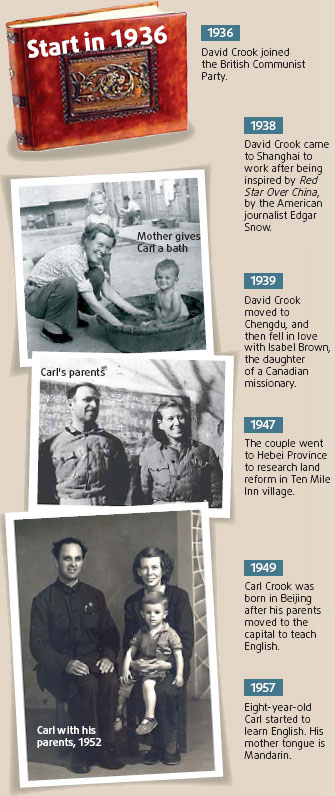

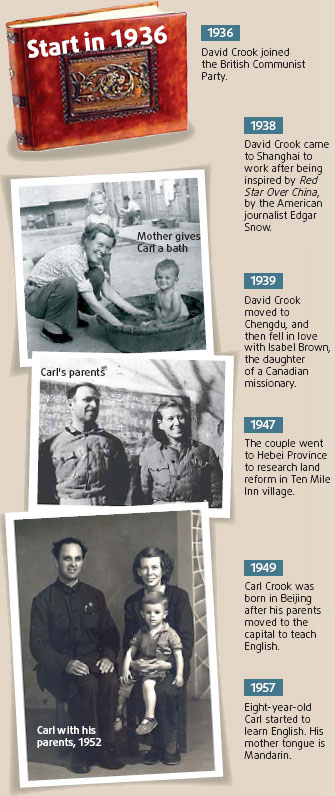

David Crook joined the British Communist Party in 1936, and then volunteered to fight with the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War (1936-39).

But the young soldier was injured on his first day on a battlefield. While recovering in hospital, he read the book Red Star Over China by the American journalist Edgar Snow. His interest in the Asian giant was piqued.

David Crook traveled to Shanghai in 1938 to teach literature and English at a church school and gather intelligence.

A year later, he had to leave the city because of the war with Japan. He moved to Chengdu, where he fell in love with Isabel Brown, the daughter of a Canadian missionary. She had been born in the capital city of Southwest China's Sichuan Province.

The two shared an interest in land reform in the country.

In 1947, the couple traveled to the country's northern region, the site of largest liberated area, to reside at a village called Ten Mile Inn, Hebei Province.

It was the first time a Chinese village had been opened to foreigners for observation since the war had broken out.

Rather than taking advantage of the benefits of living as a guest of the Communist Party of China (CPC), Crook's parents stayed and ate with local people.

During the daytime, they observed the villagers' activities. At night they arranged their notes by the light of an oil lamp.

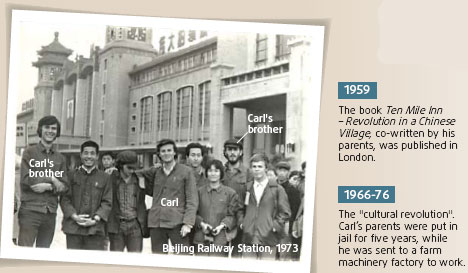

Their book, Ten Mile Inn - Revolution in a Chinese Village, was published in London in 1959.

The text examines how the village was transformed into a revolutionary battlefield and did much to help Westerners understand China's land reform.

Crook's parents were supposed to have left for England after China's liberation, but they instead accepted an offer from the CPC to become the first foreign experts to teach English in Beijing.

"I spent my childhood in a compound rather than in the alleys in which typical Beijingers grew up. From this point of view, I am a new generation of Beijinger," Crook said.

He said that in the days immediately following the establishment of the New China, more than 2 million people from across the country flocked to Beijing to help develop the capital.

Those people - which included university professors and military officials - lived in dormitories rather than ordinary dwellings, according to their social status.

However, the high enclosing walls that surrounded their residences did not entirely block out the outside world. Carl Crook's maid would often take him out for walks.

In those days it was rare to see a foreign child in the city, so he was constantly surrounded by curious onlookers who would shower him with snacks - that is, until the day he came down with stomach problems.

"After that there was always a note attached to my clothes saying 'no feeding please', like a notice at a zoo warning visitors not to feed an animal," Crook said.

"I wonder if my mother did this for me, but she never admitted to it."

Crook did not learn how to speak English until the age of eight.

"My parents were embarrassed that they had lived in China for so long, especially my mother, yet they still couldn't manage to speak Mandarin very well. They didn't want the same to happen to their children," he said.

The situation changed after he spent a year in England and Canada, during which his English improved dramatically. Communicating in English became more convenient for his parents at home.

"But when I talk with my two brothers, we always use Chinese," he said.

In order not to spoil the boy, Crook's parents sent him to a boarding school in Beijing's Chongwen District.

Most of the time he got on well with his Chinese classmates, though there were the occasional fights.

"They felt nothing but hatred, and even blamed me for the invasion by the Eight-Power Allied Forces, which took place more than half a century ago, though of course I had nothing to do with it. Somehow I wonder if they were descendants of the Chinese Boxers," he said.

"At times like those it was difficult to be a foreigner in China," he said.

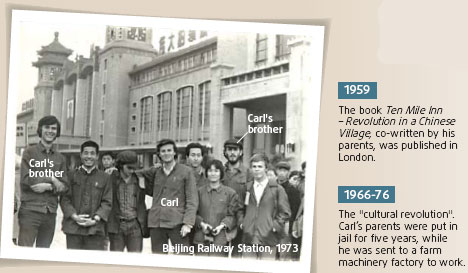

The "cultural revolution" (1966-76) proved to be a particularly dark time for the Crook family.

Both of his parents were sent to jail for five years, while he was sent to the suburbs to work first at a farm machinery factory and then at a vehicle repair factory.

"I didn't blame China for it. In fact, I regarded it as our destiny," he said.

"Honestly, I didn't suffer a lot during the revolution because a lot of people tried to help and protect us. For instance, my parents continued to get their salaries even though they were behind bars. They got 180 yuan per person each month, while I got about 20 yuan a month. So actually I was comparatively well off at the time," he said.

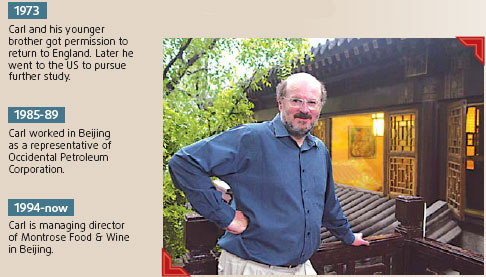

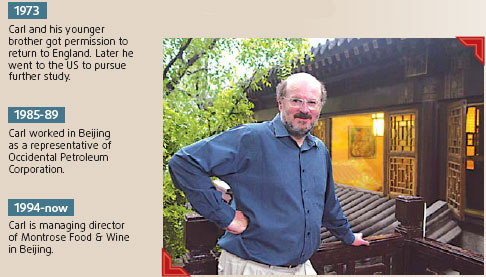

He and his younger brother tried to leave the country, but they did not get permission until 1973. The two men then set out for a nearly seven-month trip back to England.

Crook's work experience made it easier for him to find a job. Later on, he flew to the US to continue his studies.

After having gained master's degrees in education and East Asian studies, Crook returned to China in the middle of 1980s in the hope of putting his talents to good use.

His excellent Mandarin gave him an advantage over other candidates, and he became a representative of the Beijing office (1985-89) of the Occidental Petroleum Corporation, which had a coal-mine project in Shanxi Province.

His family would travel to the US every year for vacation.

He describes Beijing as a thrilling city and says he is honored to have been here to witness the many changes that have taken place since the authorities embarked on a course of economic reform.

"The older generation didn't have the opportunity to experience such transformations. We have seen thousands of years worth of changes take place in the course of a single decade in Beijing," he said

However, he is not as sanguine about the urbanization that has taken place.

He says he agrees with Liang Sicheng, the founder of Chinese modern architecture, that new cities should be built alongside old ones, rather than being mixed together in order to preserve the country's cultural heritage.

In his spare time, the Beijinger likes to study Chinese history and literature and he often visits his 92-year-old mother, who also lives in the city and remains in good health.

Crook regards Beijing as his hometown.

"Like reading one of my favorite books, the city makes me feel warm and happy inside."

(China Daily 10/16/2007 page8)