Master of Zhangshu TCM works to pass on legacy

Each morning, the soft sound of slicing fills the air at a processing workshop in Zhangshu, Jiangxi province.

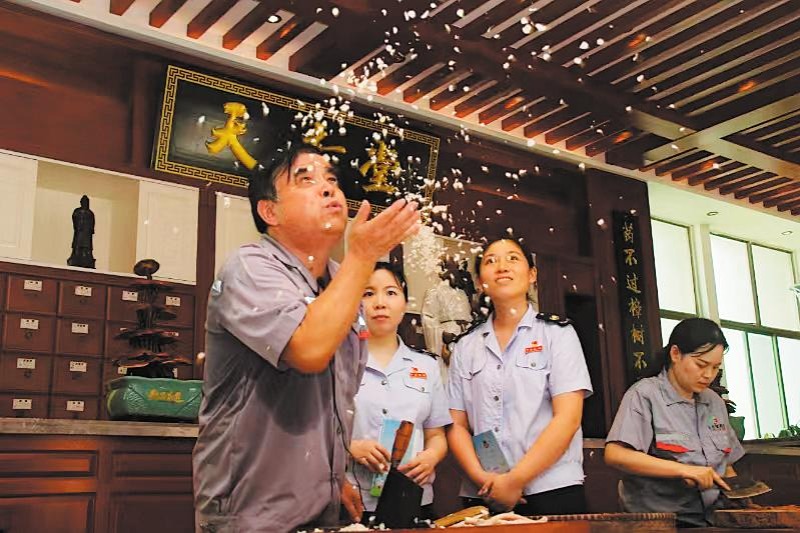

Yuan Xiaoping, 69, stands by his workbench, skillfully slicing white peony root into translucent pieces. The technique may seem effortless, but it is the result of more than 50 years of disciplined practice.

Yuan is a nationally recognized inheritor of the Zhangshu traditional Chinese medicine processing technique, a form of craftsmanship designated as national intangible cultural heritage in 2018.

For over 1,800 years, Zhangshu — known as China's medicine capital — has perfected the art of traditional herb processing, transforming raw plants into precise medicine.

This craft, known as Zhangbang techniques, relies on four signature tools: razor-sharp knives for paper-thin slicing, copper pots for controlled heating, mineral-rich local water, and secret methods passed from master to apprentice.

Born into a family with a tradition in Chinese medicine, Yuan began working as an apprentice at the old Tianqitang pharmacy at the age of 16.

He later studied under master craftsman Yu Shouxiang, known locally as the "First Blade of Zhangshu", who was renowned for his expertise in medicinal cutting.

Yuan dedicated decades to mastering core skills of the craft, including specialized methods such as wine-steaming and honey-frying.

For him, the heart of the craft lies in two skills: cutting and processing.

"Whether stir-frying, soaking, steaming, or curing — even drying, sun-baking, slicing, or storing — every step demands precision. But it's the knife work that truly stands out: each slice cut to perfect thickness, almost like art.

"Processing is not just about preparing herbs," Yuan said.

"It demands reverence for the innate properties of medicinal materials and the application of precise methods to unlock their therapeutic value."

In 2002, Yuan Xiaoping founded the Tianqitang Decoction Pieces Company, integrating TCM processing techniques with standardized modern production protocols. That same year, he established a dedicated training workshop to cultivate the next generation of TCM technicians.

By creating the company and cultivation bases, Yuan has built a complete industrial chain — from herbal cultivation and harvesting to processing, production, and sales of TCM decoction pieces.

By the end of 2024, Tianqitang Decoction Pieces reported annual revenue of 323 million yuan, driving a big growth in Zhangshu's traditional medicine industry.

To sustain the tradition, Yuan organizes regular skills competitions and invites retired master workers to teach apprentices on-site. Nearly 40 percent of his technicians are under the age of 25.

"Young people can carry the tradition forward if given the chance," he said. His students include Zhu Fulin and Liu Honglian, who now take on leadership roles themselves.

Yuan's efforts are supported by local government initiatives.

Zhangshu has introduced subsidy programs for certified heritage bearers and their apprentices. Yuan himself was named a TCM processing master of Jiangxi province, and his workshop was designated as a provincial intangible cultural heritage studio.

In addition to training, Yuan has partnered with vocational colleges to build hands-on training centers in recent years.

Students in TCM programs now visit regularly to learn slicing, roasting, and pill-making techniques in a real production environment. He has also contributed to the drafting of technical manuals and participated in regional research projects aimed at systematizing traditional practices.

Despite modern production technologies, Yuan believes many essential steps remain dependent on experience.

"Machines can cut, but they can't read the color, smell or texture of herbs," he said.

His workshop has slowly become a space for education, exchange, and even tourism, attracting visitors — including students, researchers and herbal medicine retailers — who are curious about a tradition that continues to inform modern pharmaceutical practices.

So far, Yuan has conducted 23 consecutive training workshops for specialized TCM technicians, educating over 1,500 practitioners.

"Some techniques are simple in appearance, but they require years of repetition to do well," Yuan said. "And only when passed down can they truly stay alive."

Zhang Tianyu contributed to this story.

zhaoruinan@chinadaily.com.cn

- Master of Zhangshu TCM works to pass on legacy

- Zuoquan remembers war general's sacrifice with pride

- Death toll rises to 12 in Inner Mongolia flash flood

- Local governments pitch in to offset family expenses

- Xi charts course for Xizang as region celebrates 60 years' historic progress

- Complex surgery saves man with rare injury