The Hong Kong government promotes ‘social enterprises’ to fix the city’s growing burden of aging, public health, and green challenges. Social enterprises have to generate profits to self-fund the social good. Oswald Chan reports from Hong Kong.

Pressure builds for government expenditures to cope with a rapidly aging population, the handicapped, eldercare, specialists in public health, community exercise amenities, green spaces to combat air pollution, and more. The administration struggles to reconcile its distaste for welfare spending with these new burdens.

The legacy of minimalist government for commercial activity and trade facilitation relegates responsibility for social welfare, the disabled, elderly care, and ecological conservation to private charities, church groups, clan associations, and the Jockey Club, whose surpluses are bountiful.

In 2019-20, the Hong Kong Jockey Club channeled HK$4.5 billion (US$580 million) to 210 charity and community projects, from the indirect tax on the community’s appetite for horse racing and English Premier League soccer. But even that addresses only a fraction of the city’s expanding social capital requirements.

Wealth of volunteers?

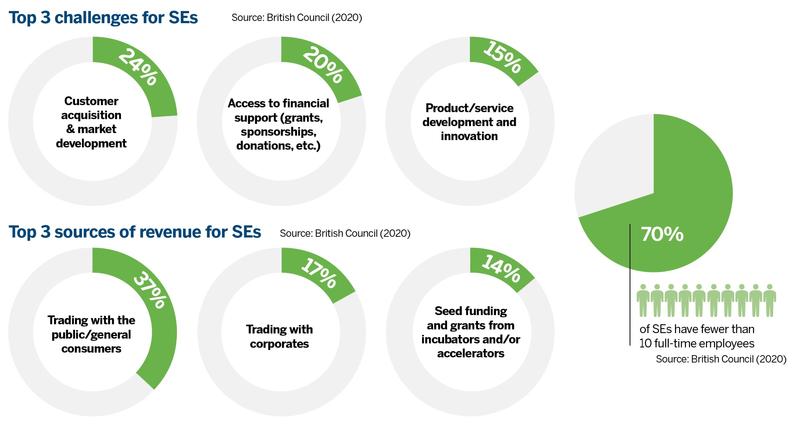

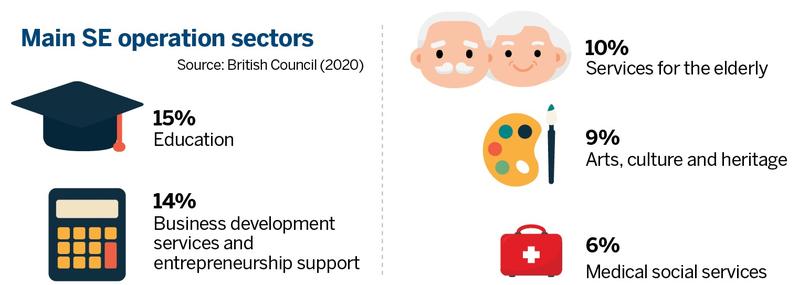

The British Council estimates there are 2,936 to 5,740 social enterprises in Hong Kong, comprising small and medium-size enterprises, charitable organizations, and cooperatives. Its social entrepreneurship report indicates they focus mostly on health, elder services, education, employment, and housing, as well as the arts, culture, and heritage.

The 2005 Commission on Poverty recommended “social enterprises” to address social needs the government avoids. In 2006, a District Partnership Program Fund came into being. The disabled are found jobs via the “Enhancing Employment of People with Disabilities through Small Enterprises Project”. To build SE capacity, money is poured into academic research and bureaucratic infrastructure for do-good champions, academics, angel and impact investors, to network for private capital to flow.

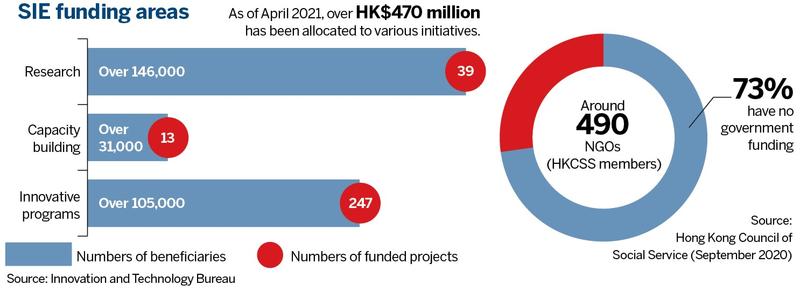

The Hong Kong Council of Social Service-Social Enterprise Business Centre, Social Entrepreneurship Forum, Social Ventures Hong Kong, the General Chamber of Social Enterprises, and Social Enterprise Summit followed in 2008. Not seeing much traction, a HK$500 million Social Innovation and Entrepreneurship Fund was approved in 2013. In 2014, the Social Enterprise Endorsement mark was issued to selected SEs by the GCSE, as an official endorsement.

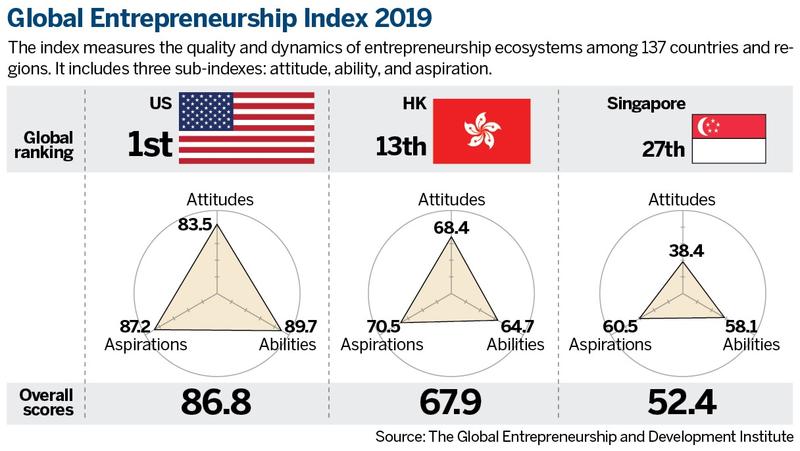

The administration places much faith and hope in the community’s entrepreneurial energy and drive to resolve social problems. The Global Entrepreneurship and Development Institute scores the US first (86.8), Hong Kong 13th (67.9), and Singapore 27th (52.4) on a composite index of a triangular matrix of attitude, aspiration, and abilities. The GEDI is the Washington-based consulting office of entrepreneurship scholars from the London School of Economics and Political Science, George Mason University in the US, the University of Pecsin Hungary, and Imperial College London.

For decades the city has functioned primarily as a financial services, real estate, and retail economy, underpinned by light bureaucracy, low taxation, no tariffs, the rule of law, and an independent judiciary, which officials touted proudly as pillars of the city’s success. Pre-COVID, the finance sector pumped up heady gains for investment funds, banks, share traders, and stock investors, driving unaffordable real estate values even higher for the common man.

21 percent poverty?

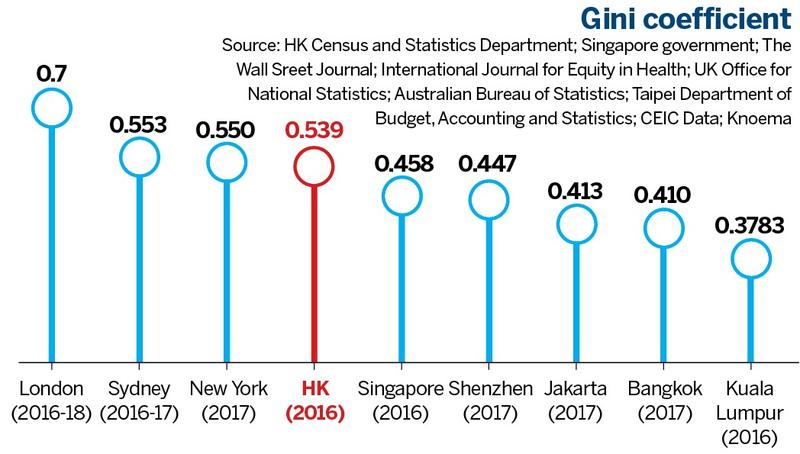

Below its glitzy harbor skyscrapers, Hong Kong conceals a shocking 21.4 percent poverty rate, confirmed in the 2019 Poverty Situation Report. More than 1.4 million Hong Kong residents live below the poverty line (HK$21,400 per month for a family of four). Hong Kong is one of the most unequal societies in the developed world.

The city’s Gini coefficient — a measure of a society’s income inequality, with zero representing perfect income equality and 1 absolute inequality — was at 0.430 in 1971, but rose to 0.539 in 2016, the highest point in the 40-year tracking. Singapore, by contrast, recorded a 2016 Gini coefficient of 0.458, with a government-managed home-ownership program covering 90 percent of citizens.

The long-unresolved home-ownership deficit is the core problem. About 45 percent of residents rent public housing in which families are allocated tiny spaces, crowding up to three generations under one roof. Social problems fester for decades — poverty, homelessness, aging, chronic disease, mental illness … the list piles up without an effective resolution.

The 2016 population census recorded 209,700 residents living in 92,700 subdivided apartments, of 3.4 lots each, across the city. These stack cubicles, like pet-shop kennels for humans, are in 10-square-meter lots. It takes an average of 5.8 years for public rental housing applicants to be offered a unit. Family life for parents and children is extremely stressful.

It is the belief in upward mobility through better education and diligent work that nourished the Hong Kong miracle. It was a city of dogged hope: the “Lion Rock” can-do spirit. The World Population Review 2019 places the city as one of the world’s most densely populated, at 6,841 residents per square kilometer, hosting a population of 7.5 million within an area of 1,104 per square km.

Apart from failing to eradicate poverty, or provide adequate affordable housing, other social objectives, like employment for the disabled, inclusiveness for ethnic minorities, facilities for the handicapped, elder welfare, public exercise facilities, ending single-use plastics, reducing the carbon footprint, etc., loom as priorities that the special administrative region has to cope with.

Avoided charity

Entrenched in the legacy government psyche is a cap on social assistance and subsidies to avoid “dependency.” Self-reliance is the mantra. “charity” is to be avoided. A limited number of the destitute are eligible for low monthly subsidies, casting a social stigma on those receiving such government aid, as a burden on the community.

It is not uncommon to see stooped folk in their 80s who are ambling carts up streets, collecting bottles and cardboard boxes to earn a living in this opulent metropolis of flashy Rolls Royces, Mercedes-Benzes, and BMWs. Visitors could never fathom such a shameful and heartless spectacle within “Asia’s World City.”

While countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development spent average 20 percent of GDP on public social expenditure in 2019, the Hong Kong government allocated 5.9 percent of GDP in its 2018-19 budget. It was 3.6 percent of GDP in 1997-98. The city does not take the lead in tackling the myriad social problems of the community. That responsibility by default goes to extended families, civil society, churches, clan associations, charity bodies, NGOs, and the Jockey Club.

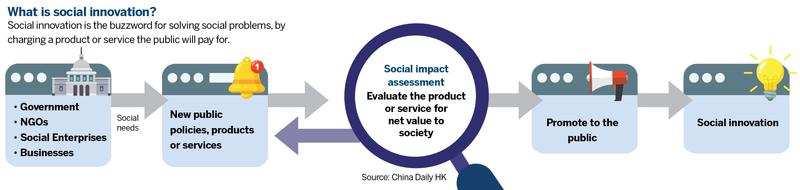

There is an effort to align the administration and chambers of commerce to promote “social enterprise innovation” for sustainable programs. Academic and business apologists construct social enterprise models, mimicking capitalist methodology. The fashionable buzzword is “social innovation”, in which “novel solutions” are spun into products and services to resolve social problems that the government dodges.

SE evolution

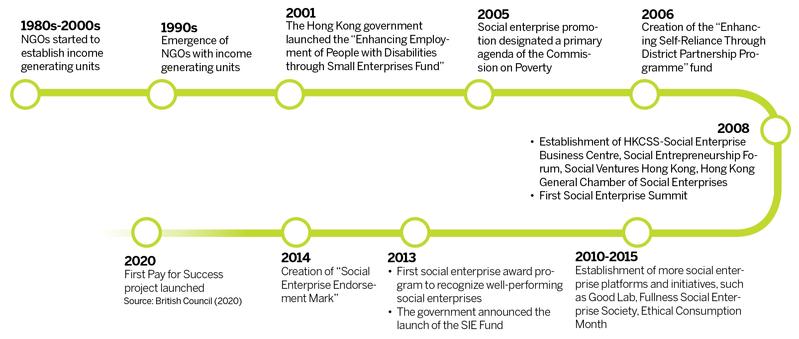

From the 1980s to early 2000s, organizations resembling social enterprises started to form. These were shelter workshops that provided employment for socially disadvantaged groups, and non-governmental organizations which fostered income-generating units.

After the economic recession of 2002-03, social enterprises were seen as catalysts for poverty and unemployment alleviation. The government established the Commission on Poverty in 2005. The commission made 53 recommendations, most of which still need to be adopted into policy and implemented.

In 2008, three major organizations of Hong Kong’s social enterprise matrix were established: the Social Entrepreneurship Forum, the Hong Kong General Chamber of Social Enterprises, and Social Ventures Hong Kong. This collective brain trust explores the role and impact of social enterprises — an elaborate talking shop.

During the 2010s, social enterprise platforms and initiatives like Good Lab, Fullness SE Society, and Ethical Consumption Month were formed to further integrate government, impact investors, and higher education institutions. That led to the establishment of the SIE Fund in 2013, and launch of the first “Pay-for-Success” project in 2020.

Ecosystem weakness

Hong Kong was ranked 13th, second after Australia in the Asia-Pacific region, in the 2019 GEDI Report, which tracks the maturity of the world’s 137 entrepreneurial ecosystems, by analyzing data of 14 pillars around entrepreneurial attitudes, abilities, and aspirations.

The GEDI index showed that Hong Kong’s SE ecosystem performed better in the sub-index of aspirations, above those of attitudes and abilities. That pointed to four major areas for improvement: want of an official definition for SEs; standardized certification; formal measurement of SE impacts on economy and society; and lack of clarity to improve the SE ecosystem.

The GCSE provides a social enterprise endorsement mark to certify SEs in the incubating, intermediate, and advanced levels, to gain public trust. The GCSE represents more than 200 social projects, of which only 50 percent have solicited GCSE certification. The reasons for that disturbing statistic are unclear.

GCSE guidelines require all certified SEs to declare a social objective: to generate at least 50 percent of revenue from business operations; and reinvest no less than 65 percent of profits in the business, for the social purpose.

GCSE Chairman Andy Ng suggested: “If there is an official definition of social enterprises, and business registration of SEs, then the government can justify certain favorable policies towards SEs, such as lower rents for leasing government premises, or favorable terms in business contracts.”

The GCSE wants the government and business sectors, as the largest purchasers of goods and services in the city, to align their procurement policies in favor of SEs when appropriate. Some social enterprises are already engaged in public contracts to deliver cleaning and catering services to government agencies, but the scope for SEs is extremely limited.

“Procurement should not only depend on the history of the service providers, or the lowest bid price, but also consider the social impact,” Rebecca Choy Yung, Organizing Committee chair of the Social Enterprise Summit, told China Daily. “In Hong Kong, procurement decisions are based on economic factors, ignoring the larger social impacts and environmental concerns.”

Our Hong Kong Foundation Researcher Johnson Kong added: “Doing good alone does not help social enterprises compete for government contracts. If the government integrates social impact assessment into its public procurement policy, companies can turn positive social impacts into business competitiveness. This would incentivize companies to measure and improve their social impacts.”

The United Kingdom’s model to leverage public procurement to promote the SE sector would be worth considering. The country’s Public Services (Social Value) Act, passed in 2012, requires UK public sector agencies to consider the economic, environmental, and social benefits when procuring a public service.

Ng goes further, saying not just the bureaucracy, but big business also, should route more business to SEs. This year, the GCSE will drum up publicity to persuade conglomerates in Hong Kong to purchase goods and services from SEs. “This kind of ‘business-to-social enterprises’ model can ensure more SEs survive to achieve their social objectives.”

Finally, a mandatory audit standard for SE goods and services can impose an independent discipline to ensure the claimed social good is being performed. That will remove residual doubts from potential public sector and corporate procurement.

Impact assessment

There is demand for a social impact assessment standard. This SIA process of systematic verification is important for SE credibility to prove claimed social objectives are achieved.

The SIA would answer these basic questions: What kind of social change? Who are the beneficiaries? How significant is the social change? What contributions? What are the risks related to the execution of the social projects? And are social resources optimally utilized in implementing the project?

Cheryl Chui, an assistant professor at the University of Hong Kong’s Department of Social Work and Social Administration, said that “SIA is important because a high-quality SIA can attract investment, increase accountability, and improve operations.”

Johnson Kong from the Our Hong Kong Foundation added: “The role of SIA is to inform the allocation of resources to different social impact projects. It creates a competitive market for impact. The competition will encourage more companies to improve their impacts.”

However, the costs of SIA analysis, like providing training to SEs, and to perform vigorous SIA assessment from control group tests, and randomized control trials, are big-ticket items for SEs. The GCSE hopes to alleviate the financial burden of SIA for qualified SEs this year.

Social-impacts data can be a common denominator of value in dollar terms to compare impacts across different industries. Hong Kong currently lacks such valuation data. There are calls for the administration to formulate a standardized social value database of non-market goods, such as life satisfaction, health status, and educational level, for SEs to use in lieu of a costly SIA audit.

Low social investment

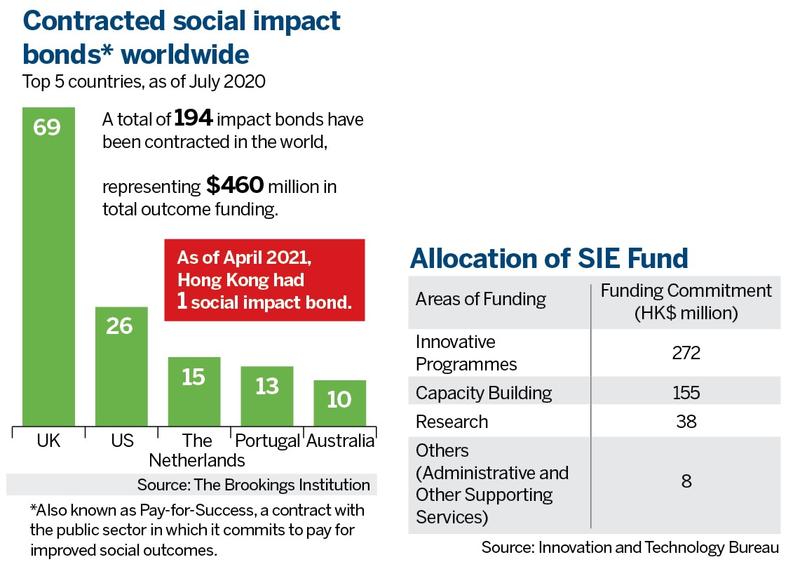

Hong Kong should also consider developing a financing market for social impacts projects to buttress its SE ecosystem. The private social investment market remains underdeveloped with low investment volumes. Angel investing and high-engagement philanthropy are also underdeveloped.

A social impact bond via blended finance or a structured fund will prioritize private investors in the senior tranche to collect returns ahead of the government and donors in the junior tranche. This structure allows government or donors, comfortable with grant-making without financial return, to mitigate the risk borne by private investors by taking the first-loss position.

In 2020, Oxfam Hong Kong scaled up its project to teach Chinese to non-Chinese-speaking students, for the city’s first social project adopting “Pay-for-Success” model, linking the public, private, and NGO sectors. The PFS model is also regarded a social impact bond.

“The beauty of this financing approach is that the government would not need to provide all the required funds for social projects. Instead, public funding is used to mobilize private investments into social enterprises,” OHKF's Kong said.

Investors will first invest, and then service providers will implement the project. An independent outcomes evaluator will measure the outcomes. Repayments plus financial return will be made only when all the outcomes are achieved. This financing model enables investors to share the risk, and ensures taxpayer money is well spent.

Contact the writer at oswald@chinadailyhk.com