background

Chernobyl: legacy & lessons

By Mike Peters (China Daily)

Updated: 2011-04-17 07:46

|

Large Medium Small |

|

|

Chernobyl was memorable for its horrific images. Thousands died as a result of the nuclear power plant accident in Ukraine. [Sergei Supinsky / Agence France-Presse ] |

Fukushima was not the first nuclear power plant leakage with contamination that spread through wind and water. Mike Peters digs deep for lessons learned since 1986.

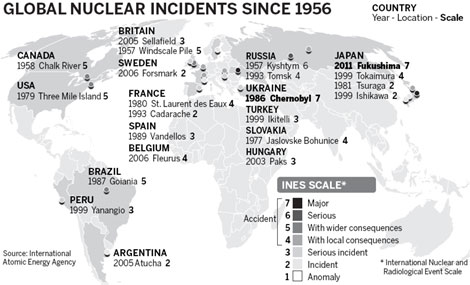

The word "Chernobyl", which has come to mean not the Ukrainian city but the 1986 nuclear accident there, still resonates across Europe a quarter-century later.

Initially, 32 people died and dozens more contracted serious radiation sickness. The World Health Organization and the United Nations say about 4,000 died eventually; other estimates range wildly higher.

Between 50 and 185 million curies of radionuclide escaped into the atmosphere - several times more radiation than the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki produced - and the winds spread the radioactivity over European forests and farmlands as far west as France and Britain.

Many farm animals were born deformed over the next years in the most affected areas.

One of the biggest health problems from Chernobyl was a steep rise in the number of children with thyroid cancer - more than 6,000 cases, according to a recent UN report. To limit chances of such an increase, people living near Fukushima are being given potassium-iodide tablets.

At Chernobyl, iodine-131 also got into the food supply through milk from cows that had fed in pastures tainted with radioactive iodine. Japan hopes to avoid this consequence by barring cows from grazing in contaminated pastures. The nation could also store any milk products or cheese for 80 days until the radioactivity is gone, says Fred Mettler, a radiology professor emeritus at the University of New Mexico who led an international team that investigated health effects from the 1986 accident.

Another risk is cesium-137, which can be spewed into the air from a nuclear plant. Its half-life is 30 years. At Chernobyl, it entered the food chain through soil and ended up in meat, berries and mushrooms. One solution is to plow up a half-meter or more of soil, Mettler says. But the isotope also leaves the body within two months, so another option is to feed livestock clean food for a few months before slaughter, Mettler told Science magazine last month.

Scott Davis, a professor of epidemiology at the University of Washington who has led three health studies in Chernobyl-affected areas, told CNN that for thyroid cases, "the worst pathway by far is through milk. Second are green and leafy vegetables, and fruits. Inhalation and water are less important." He said that about 90 percent of thyroid cancer cases around Chernobyl could have been avoided if authorities had simply told people to stop drinking milk.

The UK's Food Standards Agency, responsible for ensuring food safety by keeping products with unacceptable levels of radioactivity out of the food chain, says sheep in certain areas of Britain still contain levels of radioactivity above safety limits as a result of Chernobyl.

The agency has managed restrictions on the movement of affected sheep since 1986 to protect consumers. Farmers who want to move sheep out of a restricted area can have them tested to check their level of cesium.

In North Wales, for example, of the 5,100 holdings and 2 million sheep originally placed under restriction following the accident, 330 holdings and approximately 180,000 sheep remain within the restricted area.

Some of the fallout, then and now, has been political.

"Nuclear power - which provides about 25 percent of Germany's electricity needs - has never been close to German hearts," columnist Theo Summer wrote recently in the left-leaning German Times. "The disaster in Japan resuscitated the deep fears that had haunted the country ever since Harrisburg (Three Mile Island) and Chernobyl."

Several months ago, Chancellor Angela Merkel and her coalition partners amended a law designed to phase out nuclear energy by 2021, extending the deadline for the 17 nuclear power stations in Germany by an average of 12 years. After Fukushima she changed her mind, switching off the seven oldest reactors and declaring a three-month safety-check moratorium on the rest. Voters were unimpressed: Her Christian Democrats and Free Democrat allies got a drubbing, and the anti-nuclear Green party more than doubled its support.

"Radioactive contamination of food is the biggest health risk of a nuclear fallout, indeed," says Thilo Bode, who runs a small but influential non-profit consumer's rights organization out of Berlin called Food Watch. "We believe that the presently existing information related to this risk which is provided by public authorities in Japan, the EU and elsewhere is not sufficient." His organization, he tells China Daily, is presently working on an assessment of health risks and recommended protection limits.

| 分享按钮 |