Global General

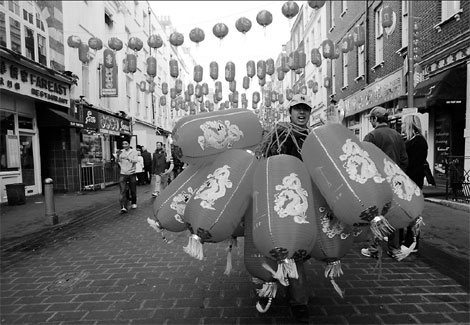

Chinese workers in UK eye impact of proposed law

By Zhang Haizhou (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-07-12 09:17

|

Large Medium Small |

|

|

Government wants threshold for gaining entry increased for skilled jobs

LONDON - Jacky Wang has been living in Britain for more than eight years and dreams of settling here permanently. But the reality is he may have to go home soon, as Britain, under a new government, has begun limiting immigration.

"I'd be lying if I said I don't want to settle here, as I've already lived here for eight years. But it's getting harder and harder now," the 28-year-old from Tianjin said in the beautiful morning sunshine of early July, gazing at skyscrapers surrounding him in Canary Wharf.

|

||||

Like Wang, they face uncertainties and the hard choice of staying on or going home.

British Home Secretary Theresa May announced on June 28 the coalition government planned an immediate interim cap of 24,100 skilled work visas for non-European Union migrants until April - 1,300 fewer than last year.

May said the threshold for gaining entry as a highly-skilled migrant had been increased by five points (from 95 to 100) to ensure only the "brightest and the best" non-EU migrants are admitted to the UK.

In an interview with the BBC, May also said there was "clear agreement" in the coalition government that a permanent cap would be set next April.

Announcing the plans in the House of Commons, she also said the government would introduce further immigration curbs, particularly on students.

Observers consider her plan an attempt by the coalition government to deliver on an election promise to cut net annual migration to the levels seen in the mid-90s.

During the campaign, David Cameron said he wanted to reduce net annual migration - the number of immigrants coming in minus the number emigrating from the UK - from hundreds of thousands to tens of thousands. The latest figure stands at 142,000, according to the Office for National Statistics.

For Wang and other Chinese expatriates hoping to settle, it's no doubt bad news. But for him it's the same old story, and the message is consistent: "It's getting harder and harder for Chinese to settle down in this country."

Few reliable or official statistics confirm the total number of Chinese nationals in the UK. But about 352,000 Chinese entered the country in 2008 alone - among whom only 88,000 were on tourist visas, according to a report by London-based Chinese Business Gazette in autumn 2009.

Wang, who is currently a network and telecom accessories salesman in central London, arrived in the country in 2002 to pursue a university degree. According to policy at that time, as he recalled, he would have needed to stay in the UK continuously for seven years to get permanent residence. About two years later it was extended to 10 years for someone in his situation, or five years if he could work continuously continuously with a work permit.

But things changed in 2008 as the Labour government introduced a points-based system to further limit immigration. The 10-year rule was also later axed, unless an immigrant had arrived in the country before July 2001.

The work permit was also replaced by categories like highly skilled and skilled workers under the point system.

Wang was lucky, as he got his work permit before the system was introduced, meaning he could still apply for settlement upon working continuously for five years.

But having been hit by continuous changes in British immigration policy, he now feels pessimistic: "I don't want to put up with this any more. Who knows what will happen tomorrow? Maybe they will change it again when I'm ready to apply for settlement?"

Wang said he has almost given up his dream, and is considering moving back to China in one or two years when his company hopes to open a branch on the southeast coast.

"Then hopefully I'll enjoy the sunshine on the beach and stay in a sea-view villa," he said, while admitting he is uncertain about it. "I have been away from China for such a long time. I have no advantage at all even though it's my own country."