PARIS - As a seven-year-old boy Jacques Franck was shown a picture of

the Mona Lisa, and a lifelong passion was born along with a single burning

question: How did Leonardo Da Vinci achieve such perfection?

Today after decades of study, years of being snubbed by academic and museum

circles and a stubborn refusal to be sidelined, this bespectacled, softly-spoken

art enthusiast says: "I have the answer."

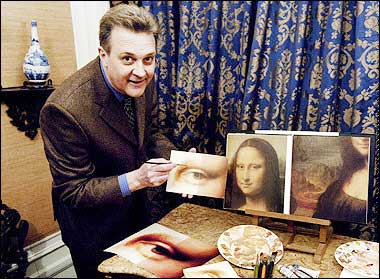

After decades of

study, years of being snubbed by academic and museum circles and a

stubborn refusal to be sidelined Jacques Franck, a consultant to the

Armand Hammer Center for Da Vinci Studies at the University of California,

seen here in his workshop, claims he has unveiled the secrets of Leonardo

da Vinci's Mona Lisa. [AFP] |

Scientists and

art historians have for centuries pored over the 500-year-old Mona Lisa seeking

to unveil the secrets of the portrait -- known as La Joconde in French -- and

her mysterious smile.

But Franck, a consultant to the Armand Hammer Center for Da Vinci Studies at

the University of California, says few have sought to elucidate the painter's

actual technique.

"From a technical point of view La Joconde defies all understanding," said

Franck, a trained artist and copyist, questioning how Da Vinci managed to

achieve such subtle play of light and shadow.

Da Vinci himself coined the phrase "sfumato", a mixture of blended and smoky

in Italian, to describe the process which he said resulted in a painting

"without lines or borders, in the manner of smoke or beyond the focus plane."

But despite leaving prodigious notes on many of his other projects and

inventions, Da Vinci never really explained how he achieved the "sfumato" effect

which lends the painting an almost a 3D quality.

"The fundamental problem with 'sfumato' is knowing how shadow and light were

linked in such an imperceptible way," said Franck.

One explanation was that Da Vinci may have smoothed the lines between colours

using his fingers and thumbs, but Franck dismisses that idea as simply far too

crude.

The Mona Lisa is painted in oils on a piece of Italian poplar and dates from

around 1503-1506, towards the end of the life of the painter who lived from 1452

to 1519.

A new book by Louvre experts due out this year reveals that traces of a

sketch have been found underneath the oil portrait.

Through a series of six panels reconstructing the Mona Lisa's eye, Franck

seeks to show that Da Vinci first painted over the sketch.

He then applied a diluted oil-based, semi-opaque wash to soften the lines and

then carefully retouched the details using dots made by a fine brush, before

applying another very thin wash in a kind of sandwich, Franck says.

Franck believes some parts of her face may have up to 30 layers on them, even

though the paint layer is incredibly thin.

"There is an extraordinary coherence in La Joconde, which shows that Da Vinci

must have worked on it for years," Franck said.

Some parts such as her famous smile and eyes may have between 30 and 40 dots

of a brush to each millimetre, requiring a magnifying glass for such close-up

work, according to his theory.

Franck is presenting his hypothesis at a 10-month Da Vinci exhibition

entitled "The Mind of Leonardo, the Universal Genius at Work" which opened in

Florence on Tuesday.

To back up his theory, he is also exhibiting two reproductions of Da Vinci's

two portraits of Saint Anne, which he painted himself using the technique.

One in coloured crayons took him some 3,000 hours of work. The other is in

oils, and both bear an uncanny similarity, even under X-rays, to the originals.

Franck's theory is raising interest in the rarified world of Da Vinci

experts.

Jean-Pierre Mohen, former head of French museums research laboratories who

oversaw the upcoming Louvre book project, said Franck's theory merited

discussion.

"He has another approach, which is not analytical, but experimental. He

brings something to the issue, it's not our way of doing things, but it is not

without interest."

What is certain is that a small painting of a woman, with a mysterious smile,

is set to haunt art lovers and experts for centuries more to come.

"It's very slow, meticulous work, with the maximum amount of reflection and

experience. And all that because of a smile which lasted less than a second,"

said Mohen.